Wetenschap

Zullen schulden, aansprakelijkheid en inheemse actie de zon zien ondergaan op de Ring van Vuur?

Een kaart van de Ring of Fire-regio. Krediet:Noront Resources Ltd.

Noront Resources Ltd., het bedrijf in het hart van de omstreden Ring of Fire-mijnbouwontwikkeling in Ontario, haalt opnieuw de krantenkoppen als onderwerp van concurrerende overnamebiedingen van mijnbouwgigant BHP Billiton en de Australische particuliere investeringsmaatschappij Wyloo Metals.

Door de biedingsoorlog is de aandelenkoers van Noront met 235 procent gestegen naar het hoogste niveau sinds 2011.

Naast de aandelenkoersen is ook de oppositie van de inheemse bevolking toegenomen, waardoor er grote vragen rijzen over de levensvatbaarheid van de voorgestelde mijnbouwactiviteiten en de waarde van de activa van Noront.

De Neskantaga First Nation en de Mushkegowuk-raad, die zeven getroffen First Nations vertegenwoordigen, betwisten openlijk de omvang en het tempo van de mijnontwikkeling op hun grondgebied. Ze bevinden zich in het gezelschap van andere First Nations in de hele regio die jarenlang hun politieke en territoriale autoriteit hebben laten gelden in het licht van de voorgestelde plannen van Noront.

Bevoegdheid doen gelden

Inheemse jurisdictie en de ontkenning ervan door de autoriteiten hebben een enorme impact gehad op het fortuin van Noront. De ontwikkeling van de vlaggenschipmijn van het bedrijf is sinds 2011 tot stilstand gekomen, net als de 300 kilometer lange industriële weg die het hele jaar door de "weg naar nergens" wordt genoemd vanwege de twijfelachtige economische vooruitzichten - die nodig is om toegang te krijgen tot het afgelegen mijnbouwgebied.

Dit komt omdat de First Nations van de regio consequent hebben geëist dat Ontario hun jurisdictie over hun land en territoria erkent. De Matawa-naties, waaronder Neskantaga, dwongen de provincie aanvankelijk om te onderhandelen over een gedeelde regionale benadering van besluitvorming.

Dat zogenaamde Regionale Kaderakkoord verhinderde de provincie om eenzijdig de ontwikkeling van inheems land te sanctioneren, maar werd uiteindelijk in 2019 door de provincie ontbonden.

Inheemse autoriteiten hebben sindsdien hun jurisdictie in de regio blijven doen gelden. Meest recentelijk dringt een coalitie van drie First Nations (Attawapiskat, Fort Albany en Neskantaga) erop aan dat een nieuw opgestelde regionale beoordeling van de cumulatieve effecten van voorgestelde mijn- en wegontwikkelingen door inheemsen wordt geleid.

Gedurende deze periode zijn de aandelen van Noront gekelderd van bijna $ 2 aan het begin van 2010 tot minder dan 20 cent sinds 2019. De schuld van het bedrijf is sinds 2013 met ten minste $ 100 miljoen gestegen tot $ 299 miljoen op 31 december 2020 en de uitstaande leningen staan op $ 51,4 miljoen.

Ondanks toenemend bewijs dat de waarde van het bedrijf en zijn activa instemming van de inheemse bevolking vereist, zijn federale en provinciale overheden honderden miljoenen dollars blijven steken in mijnbouwontwikkelingen in de Ring of Fire in de vorm van exploratiefinanciering en infrastructuurondersteuning.

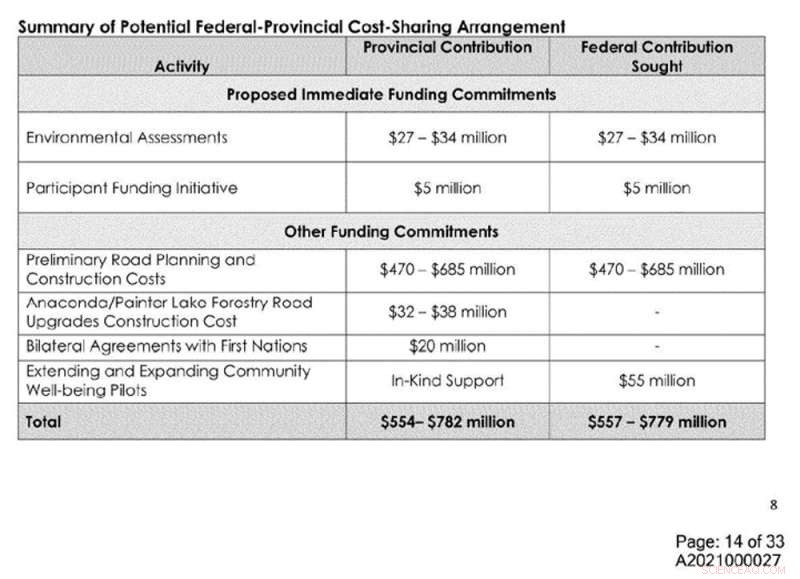

Een screenshot van interne documenten verkregen via een Freedom of Information-verzoek toont de omvang van de provinciale en federale investeringen in de voorgestelde Ring of Fire-ontwikkeling. (Auteur verstrekt)

Miljoenen voor verkenning

Terwijl goedkeuringsprocessen zich voortsleepten en vervolgens vastliepen, heeft Noront – gesteund door federale en provinciale schatkisten – geprobeerd waarde te creëren door zijn activa te vergroten en zijn verkenningsprogramma uit te breiden.

Sinds december 2008 blijkt uit de registraties van het bedrijf dat de federale en Ontario-regeringen Noront's Ring of Fire-exploratieprogramma's hebben gesubsidieerd voor een bedrag van bijna $ 45 miljoen via een fiscaal mechanisme dat bekend staat als doorstroomfinanciering.

That mechanism allows firms to raise exploration funds from investors and return tax credits to them.

Additional federal and provincial refundable tax credits are also available to flow-through investors, resulting in the transfer of millions of dollars—money that would have otherwise been tax revenue—to Noront's exploration of the Ring of Fire. According to the company's aforementioned regulatory filings, Noront has raised more than $75 million of flow-through financing since 2008 for Ring of Fire properties.

This flow of government money reveals a system of economic relationships described by the Yellowhead Institute, a First Nations-led research center, as colonial and predatory.

Amid Indigenous demands to determine and control the pace of development in their territories and to create the institutions required to do so, this flow of money also raises serious concerns about the financial realities of the Ring of Fire project.

Circumventing Indigenous jurisdiction

While the province once estimated the cost of implementing the doomed framework agreement to be slightly over $20 million, the cost of circumventing Indigenous jurisdiction is much higher.

Since tearing up the agreement in 2019 in an attempt to speed up development, Ontario has entered into bilateral funding agreements worth $20 million with two First Nations currently serving as proponents of the all-season road.

According to documents obtained though an Access to Information request, it's also currently negotiating a planning agreement worth $38 million with another First Nation.

Internal documents obtained via a Freedom of Information request details Ontario’s proposal of a cost-share arrangement with Ottawa on the all-season road in the Ring of Fire. (Author provided), Author provided

These same documents reveal the federal government spent approximately $11 million annually since 2016 to fund so-called community well-being projects in five Matawa communities. These are programs purportedly aimed at improving "community readiness" for mining operations in the Ring of Fire.

If Ontario has its way, this funding will be renewed at a total of $55 million over five years. Between 2010 and 2015, Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada contributed nearly $16 million through the strategic partnership initiative to "support First Nations mining readiness activities" in the area, an investment topped up by a few million in 2016.

It also contributed $255 million over two years to a First Nations fund partially earmarked to support regional infrastructure in the Ring of Fire and intended to encourage compliance with mining projects.

A 2019 intergovernmental memo—also obtained via the Freedom of Information request—shows the federal government also offered to "explore options to advance Ring of Fire projects" using money that was designated for well-being projects in Indigenous communities.

There's also the matter of the $1.6 billion all-season road. Ontario has promised to fund the road through the homelands of multiple First Nations, most recently through a proposed cost-share arrangement with Ottawa.

Debt, debt and more debt

Noront has consistently under-represented to investors, and now to corporate suitors, the legal and financial liabilities associated with Indigenous jurisdiction—and there are many.

Regardless of who successfully bids for the company, opposition to the Ring of Fire project is only likely to increase unless First Nations are empowered to exercise real control over the decisions that will impact them. This raises the specter of litigation, Indigenous land defense actions—and more debt.

According to the internal documents, the federal and provincial government are expecting to earn $4.4 billion in combined tax revenues during the first 10 years of the proposed mine's operation. But if they add up the amount of money they've already paid to defy and circumvent Indigenous jurisdiction, and the financial costs associated with continuing to do so, that $4.4 billion will soon be exhausted.

It is entirely likely that any profits related to this enterprise have already been spent. The question that remains is who will be left holding the debt?

Dalend zicht toont aan dat Afrikaanse steden met grote luchtvervuiling te kampen hebben

Dalend zicht toont aan dat Afrikaanse steden met grote luchtvervuiling te kampen hebben Menselijke activiteit heeft het Murray-estuarium kwetsbaarder gemaakt voor droogte

Menselijke activiteit heeft het Murray-estuarium kwetsbaarder gemaakt voor droogte 41 grote vervuilers krijgen gratis passen op de koolstofhandelsmarkt in de staat Washington

41 grote vervuilers krijgen gratis passen op de koolstofhandelsmarkt in de staat Washington Over een Wolfs Geurgeur

Over een Wolfs Geurgeur Canadese provincie belooft strijd tegen pijpleiding voort te zetten

Canadese provincie belooft strijd tegen pijpleiding voort te zetten

Hoofdlijnen

- CMU-software assembleert RNA-transcripten nauwkeuriger

- Bloeiende onderwatertuinen gevonden voor de kust van Wellington

- Waarom doden we?

- Haaienvinnenverboden helpen haaien misschien niet, wetenschappers zeggen:

- Wat als Homeostase mislukt?

- Microbiologen verbeteren de smaak van bier

- Wat eronder ligt:wortels als drijvende krachten achter het Zuid-Afrikaanse landschapspatroon

- De biodiversiteit van de aarde verandert naarmate de planeet opwarmt. Maar hoe?

- Wat is vijver? Onderzoek levert eerste datagestuurde definitie op

Galileo:Europa's rivaal van GPS

Galileo:Europa's rivaal van GPS Behuizing uit de Bronstijd zou de vroegste aanwijzingen kunnen geven over de oorsprong van Cardiff

Behuizing uit de Bronstijd zou de vroegste aanwijzingen kunnen geven over de oorsprong van Cardiff Hoe gletsjertafels worden gevormd

Hoe gletsjertafels worden gevormd Chemische aantrekkingskracht geeft ratelslangpeptide de beet op superbacteriën

Chemische aantrekkingskracht geeft ratelslangpeptide de beet op superbacteriën Speciale en standaard koffiebonen kunnen worden gesorteerd met behulp van multispectrale beeldvorming en kunstmatige intelligentie

Speciale en standaard koffiebonen kunnen worden gesorteerd met behulp van multispectrale beeldvorming en kunstmatige intelligentie Nieuwe lichtgevende quasar gedetecteerd door astronomen

Nieuwe lichtgevende quasar gedetecteerd door astronomen Enquête:de meeste Amerikanen willen dat de overheid zich inzet om ongelijkheid te verminderen

Enquête:de meeste Amerikanen willen dat de overheid zich inzet om ongelijkheid te verminderen Hoe te omzetten Radian naar Minuten

Hoe te omzetten Radian naar Minuten

- Elektronica

- Biologie

- Zonsverduistering

- Wiskunde

- French | Italian | Spanish | Portuguese | Swedish | German | Dutch | Danish | Norway |

-

Wetenschap © https://nl.scienceaq.com