Wetenschap

Pacifische ratten spoor 2, 000 jaar menselijke impact op eilandecosystemen

Agakauitai-eiland in de Gambier-archipel (Mangareva). Krediet:Jillian A. Swift

Chemische analyse van de overblijfselen van ratten van archeologische vindplaatsen van de afgelopen 2000 jaar op drie Polynesische eilandsystemen heeft de impact van mensen op de lokale omgeving aangetoond. De analyse door een internationaal team van wetenschappers stelde de onderzoekers in staat het dieet van de ratten te reconstrueren - en via hen, de veranderingen die mensen aanbrengen in lokale ecosystemen, inclusief het uitsterven van inheemse soorten en veranderingen in voedselwebben en bodemvoedingsstoffen.

De aarde is een nieuw geologisch tijdperk ingegaan dat het Antropoceen wordt genoemd. een tijdperk waarin de mens belangrijke, blijvende verandering van de planeet. Terwijl de meeste geologen en ecologen de oorsprong van dit tijdperk in de laatste 50 tot 300 jaar plaatsen, veel archeologen hebben betoogd dat verreikende menselijke effecten op de geologie, biodiversiteit, en klimaat gaan millennia terug in het verleden.

Oude menselijke effecten zijn vaak moeilijk te identificeren en te meten in vergelijking met die van vandaag of in de recente geschiedenis. Een nieuwe studie gepubliceerd in de Proceedings van de National Academy of Sciences door onderzoekers van het Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena en de University of California, Berkeley introduceert een nieuwe methode voor het detecteren en kwantificeren van menselijke transformaties van lokale ecosystemen in het verleden. Met behulp van de modernste methoden, onderzoekers zochten naar aanwijzingen over eerdere menselijke modificaties van eilandecosystemen uit een ongebruikelijke bron - de botten van lang geleden overleden ratten die zijn teruggevonden op archeologische vindplaatsen.

Een van de meest ambitieuze en wijdverbreide migraties in de menselijke geschiedenis begon c. 3000 jaar geleden, toen mensen over de Stille Oceaan begonnen te reizen - voorbij de zichtbare horizon - op zoek naar nieuwe eilanden. Ongeveer 1000 jaar geleden, mensen hadden zelfs de meest afgelegen kusten in de Stille Oceaan bereikt, inclusief de grenzen van de Polynesische regio:de eilanden Hawaï, Rapa Nui (Paaseiland) en Aotearoa (Nieuw-Zeeland). Niet wetende wat ze zouden tegenkomen in deze nieuwe landen, vroege reizigers brachten een reeks bekende planten en dieren mee, inclusief gewassen zoals taro, broodvrucht, en yams, en dieren, waaronder het varken, hond, en kip. Onder de nieuwkomers bevond zich ook de Pacifische rat (Rattus exulans), die tijdens deze vroege reizen naar bijna elk Polynesisch eiland werd vervoerd, misschien opzettelijk als voedsel, of even waarschijnlijk, als een verborgen "verstekeling" aan boord van langeafstandskano's.

Opgraving van 'Kitchen Cave' Rockshelter (KAM-1) in volle gang. Kamaka-eiland, Gambier-archipel (Mangareva). Krediet:Patrick V. Kirch

De komst van de rat had grote gevolgen voor de ecosystemen van eilanden. Pacifische ratten jaagden op lokale zeevogels en aten de zaden van endemische boomsoorten. belangrijk, commensale dieren zoals de Pacifische rat nemen een unieke positie in in menselijke ecosystemen. Zoals huisdieren, ze brengen het grootste deel van hun tijd door in en rond menselijke nederzettingen, overleven op voedsel dat door mensen wordt geproduceerd of verzameld. Echter, in tegenstelling tot hun binnenlandse tegenhangers, deze commensale soorten worden niet rechtstreeks door mensen beheerd. Their diets thus provide insights into the food available in human settlements as well as changes to island ecosystems more broadly.

But how to reconstruct the diet of ancient rats? To do this, the researchers examined the biochemical composition of rat bones recovered from archaeological sites across three Polynesian island systems. Carbon isotope analysis of proteins preserved in archaeological bone indicates the types of plants consumed, while nitrogen isotopes point to the position of the animal in a food web. Nitrogen isotopes are also sensitive to humidity, soil quality, and land use. This study examined the carbon and nitrogen isotopes of archaeological Pacific rat remains across seven islands in the Pacific, spanning roughly 2000 years of human occupation. The researchers' results demonstrate the impacts of processes like human forest clearance, hunting of native avifauna (in particular land birds and seabirds) and the development of new, agricultural landscapes on food webs and resource availability.

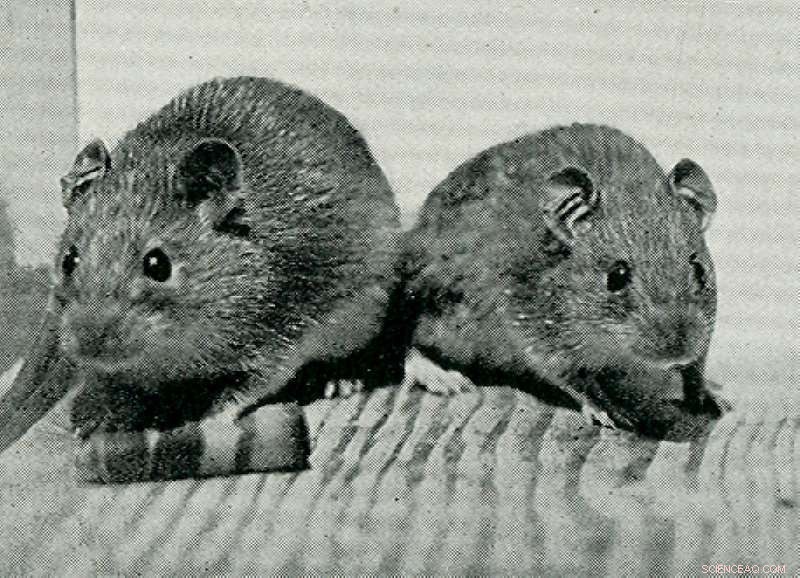

Pacific rats ( Rattus exulans ). Credit:Photo taken by John Stokes (Bernice P. Bishop Museum), and courtesy of Patrick V. Kirch.

A near-universal pattern of changing rat bone nitrogen isotope values through time was linked to native species extinctions and changes in soil nutrient cycling after people arrived on the islands. In addition, significant changes in both carbon and nitrogen isotopes correspond with agricultural expansion, human site activity, and subsistence choices. "We have many strong lines of archaeological evidence for humans modifying past ecosystems as far back as the Late Pleistocene, " says lead author Jillian Swift, of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. "The challenge is in finding datasets that can quantify these changes in ways that allow us to compare archaeological and modern datasets to help predict what impacts human modifications will have on ecosystems in the future."

Prof. Patrick V. Kirch of the University of California, Berkeley, who supervised the study and led excavations on Tikopia and Mangareva, remarked that "the new isotopic methods allow us to quantify the ways in which human actions have fundamentally changed island ecosystems. I hardly dreamed this might be possible back in the 1970s when I excavated the sites on Tikopia Island."

"Commensal species, such as the Pacific rat, are often forgotten about in archaeological assemblages. Although they are seen as less glamorous 'stowaways' when compared to domesticated animals, they offer an unparalleled opportunity to look at the new ecologies and landscapes created by our species as it expanded across the face of the planet, " added Patrick Roberts of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, a co-author on the paper. "The development and use of stable isotope analysis of commensal species raises the possibility of tracking the process of human environment modification, not just in the Pacific, but around the world where they are found in association with human land use."

The study highlights the extraordinary degree to which people in the past were able to modify ecosystems. "Studies like this clearly highlight the human capacity for 'ecosystem engineering, '" notes Nicole Boivin, coauthor of the study and Director of the Department of Archaeology at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. "We clearly have long had the capability as a species of massively transforming the world around us. What's new today is our ability to understand, measure, and alleviate these impacts."

Onderzoekers ontdekken zeldzaam Antarctisch drakenhuidijs

Onderzoekers ontdekken zeldzaam Antarctisch drakenhuidijs Betere manieren vinden om af te koelen als het klimaat warmer wordt

Betere manieren vinden om af te koelen als het klimaat warmer wordt Afvloeiing van Harvey bedreigt koraalriffen in Texas

Afvloeiing van Harvey bedreigt koraalriffen in Texas Problemen met schone lucht nemen een toppositie in bij de prioriteiten van het Bidens-agentschap

Problemen met schone lucht nemen een toppositie in bij de prioriteiten van het Bidens-agentschap Het Great Barrier Reef heeft de helft van zijn koralen verloren

Het Great Barrier Reef heeft de helft van zijn koralen verloren

Hoofdlijnen

- Hoe HeLa-cellen werken

- Wat gebeurt er als een kind wordt geboren met een extra chromosoom in het 23e paar?

- Twilight-truc:er is een nieuw type cel gevonden in het oog van een diepzeevis

- Onderzoek naar schapengenen kan helpen om gezondere dieren te fokken

- Gegevensmodellering is de sleutel tot duurzaam visserijbeheer

- Nieuwe strategie zou bestaande medicijnen in staat kunnen stellen bacteriën te doden die chronische infecties veroorzaken

- Kinesins negeren zwakke krachten omdat ze zware lasten dragen

- Wat is een eigenschap die het resultaat is van twee dominante genen?

- Wat gebeurt er wanneer Pepsin zich mengt met voedsel in de maag?

- Ironie is het nieuwe zwart

- Antropologen bevestigen het bestaan van een gespecialiseerd jachtkamp voor schapen in het prehistorische Libanon

- Zeldzame 450 miljoen jaar oude kegelvormige fossiele ontdekking

- Feiten van fictie online beoordelen

- Sterke stofstormen in de winter hebben mogelijk de ineenstorting van het Akkadische rijk veroorzaakt

Duitse rechtbank zegt dat Tesla bomen mag vellen op locatie nieuwe fabriek

Duitse rechtbank zegt dat Tesla bomen mag vellen op locatie nieuwe fabriek Miljoenen in het VK hebben te maken met waterbeperkingen te midden van hete, droog weer

Miljoenen in het VK hebben te maken met waterbeperkingen te midden van hete, droog weer Wetenschappers ontdekken een topologische magneet die exotische kwantumeffecten vertoont

Wetenschappers ontdekken een topologische magneet die exotische kwantumeffecten vertoont Een mogelijke nieuwe manier om computerchips te koelen

Een mogelijke nieuwe manier om computerchips te koelen Een stap dichter bij het aanraken van asteroïde Bennu

Een stap dichter bij het aanraken van asteroïde Bennu Waarom is koolstof zo belangrijk voor organische verbindingen?

Waarom is koolstof zo belangrijk voor organische verbindingen?  Nieuw rapport onthult uitgavengedrag van cybercriminelen

Nieuw rapport onthult uitgavengedrag van cybercriminelen Afgelegen Amazone-steden kwetsbaarder voor klimaatverandering

Afgelegen Amazone-steden kwetsbaarder voor klimaatverandering

- Elektronica

- Biologie

- Zonsverduistering

- Wiskunde

- Spanish | Portuguese | Swedish | German | Dutch | Danish | French | Italian | Norway |

-

Wetenschap © https://nl.scienceaq.com