Wetenschap

Onderzoekers ontdekken uitgestorven prehistorisch reptiel dat tussen dinosauriërs leefde

Een artistieke interpretatie van een nieuw ontdekte uitgestorven soort hagedisachtig reptiel dat tot dezelfde oude afstamming behoort als de levende tuatara in Nieuw-Zeeland. De nieuw ontdekte Opisthiamimus gregori jaagt op een inmiddels uitgestorven waterwants (Morrisonnepa jurassica), terwijl op de achtergrond de roofzuchtige dinosaurus Allosaurus jimmadseni zijn nest bewaakt. Het tafereel is de uiterwaarden van een rivier in het late Jura Wyoming, ongeveer 150 miljoen jaar geleden. Krediet:Julius Csotonei voor het Smithsonian Institution

Smithsonian-onderzoekers hebben een nieuwe uitgestorven soort hagedisachtig reptiel ontdekt die tot dezelfde oude afstamming behoort als de levende tuatara in Nieuw-Zeeland. Een team van wetenschappers, waaronder de conservator van Dinosauria Matthew Carrano van het National Museum of Natural History en onderzoeksmedewerker David DeMar Jr., evenals University College London en Natural History Museum, Londens wetenschappelijk medewerker Marc Jones, beschrijft de nieuwe soort Opisthiamimus gregori, die ooit bewoonde Jurassic Noord-Amerika ongeveer 150 miljoen jaar geleden samen met dinosaurussen zoals Stegosaurus en Allosaurus, in een artikel dat vandaag is gepubliceerd in het Journal of Systematic Paleontology . In het leven zou dit prehistorische reptiel ongeveer 16 centimeter (ongeveer 6 inch) van neus tot staart zijn geweest - en zou het opgerold in de palm van een volwassen mensenhand passen - en waarschijnlijk overleefden op een dieet van insecten en andere ongewervelde dieren.

"Wat belangrijk is aan de tuatara, is dat het dit enorme evolutionaire verhaal vertegenwoordigt dat we het geluk hebben om te vangen in wat waarschijnlijk zijn slotact is," zei Carrano. "Hoewel het eruit ziet als een relatief eenvoudige hagedis, belichaamt het een heel evolutionair epos dat meer dan 200 miljoen jaar teruggaat."

De ontdekking is afkomstig van een handvol exemplaren, waaronder een buitengewoon compleet en goed bewaard gebleven fossielskelet dat is opgegraven op een locatie rond een Allosaurus-nest in de Morrison-formatie in het noorden van Wyoming. Verdere studie van de vondst zou kunnen helpen onthullen waarom de oude orde van reptielen van dit dier werd gezift van divers en talrijk in het Jura tot alleen de Nieuw-Zeelandse tuatara die vandaag de dag nog bestaat.

De tuatara lijkt een beetje op een bijzonder stevige leguaan, maar de tuatara en zijn nieuw ontdekte verwant zijn in feite helemaal geen hagedissen. Het zijn eigenlijk rhynchocephalians, een orde die minstens 230 miljoen jaar geleden afweek van hagedissen, zei Carrano.

In hun Jura-hoogtijdagen werden rhynchocephalians bijna wereldwijd gevonden, waren er in grote en kleine maten, en vervulden ecologische rollen, variërend van jagers op watervissen tot omvangrijke planteneters. Maar om redenen die nog steeds niet volledig worden begrepen, zijn rhynchocephalians vrijwel verdwenen toen hagedissen en slangen uitgroeiden tot de meest voorkomende en meer diverse reptielen over de hele wereld.

Deze evolutionaire kloof tussen hagedissen en rhynchocephalians verklaart de vreemde kenmerken van de tuatara, zoals tanden die aan het kaakbot zijn versmolten, een unieke kauwbeweging die de onderkaak heen en weer schuift als een zaagblad, een levensduur van meer dan 100 jaar en een tolerantie voor koudere klimaten.

Volgens de formele beschrijving van O. gregori zei Carrano dat het fossiel is toegevoegd aan de collecties van het museum waar het beschikbaar zal blijven voor toekomstig onderzoek, misschien op een dag om onderzoekers te helpen erachter te komen waarom de tuatara het enige is dat overblijft van de rhynchocephalians, terwijl hagedissen nu worden gevonden over de hele wereld.

Fossiel skelet van het nieuwe hagedisachtige reptiel Opisthiamimus gregori. The fossil was discovered in the Morrison Formation of the Bighorn Basin, north-central Wyoming, and dates to the Late Jurassic Period, approximately 150 million years ago. Researchers named the new species after Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History volunteer Joseph Gregor who spent hundreds of hours meticulously scraping and chiseling the bones from a block of stone that first caught museum fossil preparator Pete Kroehler’s eye back in 2010. The fossil has been added to the museum’s collections where it will remain available for future study. Credit:David DeMar for the Smithsonian Institution

"These animals may have disappeared partly because of competition from lizards but perhaps also due to global shifts in climate and changing habitats," Carrano said. "It's fascinating when you have the dominance of one group giving way to another group over evolutionary time, and we still need more evidence to explain exactly what happened, but fossils like this one are how we will put it together."

The researchers named the new species after museum volunteer Joseph Gregor who spent hundreds of hours meticulously scraping and chiseling the bones from a block of stone that first caught museum fossil preparator Pete Kroehler's eye back in 2010.

"Pete is one of those people who has a kind of X-ray vision for this sort of thing," Carrano said. "He noticed two tiny specks of bone on the side of this block and marked it to be brought back with no real idea what was in it. As it turns out, he hit the jackpot."

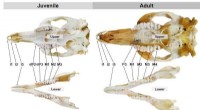

The fossil is almost entirely complete, with the exception of the tail and parts of the hind legs. Carrano said that such a complete skeleton is rare for small prehistoric creatures like this because their frail bones were often destroyed either before they fossilized or as they emerge from an eroding rock formation in the present day. As a result, rhynchocephalians are mostly known to paleontologists from small fragments of their jaws and teeth.

After Kroehler, Gregor and others had freed as much of the tiny fossil from the rock as was practical given its fragility, the team, led by DeMar, set about scanning the fossil with high-resolution computerized tomography (CT), a method that uses multiple X-ray images from different angles to create a 3D representation of the specimen. The team used three separate CT scanning facilities, including one housed at the National Museum of Natural History, to capture everything they possibly could about the fossil.

Once the fossil's bones had been digitally rendered with accuracy smaller than a millimeter, DeMar set about reassembling the digitized bones of the skull, some of which were crushed, out of place or missing on one side, using software to eventually create a nearly complete 3D reconstruction. The reconstructed 3D skull now provides researchers an unprecedented look at this Jurassic-age reptile's head.

Given Opisthiamimus's diminutive size, tooth shape and rigid skull, it likely ate insects, said DeMar, adding that prey with harder shells such as beetles or water bugs might have also been on the menu. Broadly speaking, the new species looks quite a bit like a miniaturized version of its only surviving relative (tuataras are about five times longer).

"Such a complete specimen has huge potential for making comparisons with fossils collected in the future and for identifying or reclassifying specimens already sitting in a museum drawer somewhere," DeMar said. "With the 3D models we have, at some point we could also do studies that use software to look at this critter's jaw mechanics." + Verder verkennen

Ancient salamander was hidden inside mystery rock for 50 years—new research

Nieuwe styreenproductiemethode verbetert de stabiliteit, dehydrogeneringsactiviteit

Nieuwe styreenproductiemethode verbetert de stabiliteit, dehydrogeneringsactiviteit Een nieuw antiseizure-doelwit?

Een nieuw antiseizure-doelwit? Nieuwe tool is bedoeld om COVID-19 te bestrijden, andere ziekten

Nieuwe tool is bedoeld om COVID-19 te bestrijden, andere ziekten Defect- en interface-engineering voor e-NRR onder omgevingsomstandigheden

Defect- en interface-engineering voor e-NRR onder omgevingsomstandigheden Eiwit afgeleid van haver is in nieuwe techniek gekoppeld aan celzelfmoord-enzym

Eiwit afgeleid van haver is in nieuwe techniek gekoppeld aan celzelfmoord-enzym

Het risico op catastrofale megaoverstromingen in Californië is verdubbeld door de opwarming van de aarde, zeggen onderzoekers

Het risico op catastrofale megaoverstromingen in Californië is verdubbeld door de opwarming van de aarde, zeggen onderzoekers Experts pleiten voor herziening van regelgeving inzake pesticiden

Experts pleiten voor herziening van regelgeving inzake pesticiden 2017 wordt waarschijnlijk het derde warmste jaar ooit

2017 wordt waarschijnlijk het derde warmste jaar ooit NASA bespioneert windschering nog steeds van invloed op tropische storm Nalgae

NASA bespioneert windschering nog steeds van invloed op tropische storm Nalgae Guatemala's Pacaya-vulkaan blijft na 50 dagen uitbarsten

Guatemala's Pacaya-vulkaan blijft na 50 dagen uitbarsten

Hoofdlijnen

- Oude kikkers in massagraf stierven door te veel seks, zegt nieuw onderzoek

- Het redden van Indonesische paradijsvogels dorp voor dorp

- Voors en tegens van Cloning Plants & Animals

- Wetenschapsprojecten over Dominant en Recessieve Genen

- Waarom zijn mensen altruïstisch?

- Hoe meet je geluk?

- Doorbraak kan tuinders helpen bij het zaaien van zaden

- Wat zijn de zuignappen op een octopus genoemd?

- Vergelijk en contrast kunstmatige en natuurlijke selectie

- Een omkeerbare hoofdschakelaar ontdekken voor ontwikkeling

- Klimaatverandering:kunnen kolibries de hitte aan?

- Waarom laten mensen twee sets tanden groeien? Deze buideldieren herschrijven het verhaal van tandheelkundige evolutie

- De persoonlijke beschermingsmiddelen die tijdens de COVID-19-pandemie worden gebruikt, raken verstrikt in wilde dieren

- Ontdekking van nieuwe soorten microfossielen kan eeuwenoude wetenschappelijke vragen beantwoorden

Geluidsoverlast door fracken kan de menselijke gezondheid schaden

Geluidsoverlast door fracken kan de menselijke gezondheid schaden Acht op de tien leraren vinden onderwijsnieuws negatief en demoraliserend

Acht op de tien leraren vinden onderwijsnieuws negatief en demoraliserend Shagene Een synthese geperfectioneerd voor de behandeling van leishmaniasis

Shagene Een synthese geperfectioneerd voor de behandeling van leishmaniasis De COVID-19-lockdown in Kenia dwingt mensen om moeilijke beslissingen te nemen over voedsel en huishoudelijke energie

De COVID-19-lockdown in Kenia dwingt mensen om moeilijke beslissingen te nemen over voedsel en huishoudelijke energie Ontsnappen aan het gebrul van monsters:een verhaal over overlevenden van een orkaan in de VS

Ontsnappen aan het gebrul van monsters:een verhaal over overlevenden van een orkaan in de VS NASA telt af voor lancering laserstudie van ijskappen

NASA telt af voor lancering laserstudie van ijskappen Het luchthavenplan van Chicago is een van de vele droomprojecten van Musk

Het luchthavenplan van Chicago is een van de vele droomprojecten van Musk Gek worden? Train dan als een astronaut, ruimte nabootsen

Gek worden? Train dan als een astronaut, ruimte nabootsen

- Elektronica

- Biologie

- Zonsverduistering

- Wiskunde

- French | Italian | Spanish | Portuguese | Swedish | German | Dutch | Danish | Norway |

-

Wetenschap © https://nl.scienceaq.com