Wetenschap

Tassen of bakken? Als het om recycling gaat, is het antwoord ingewikkeld

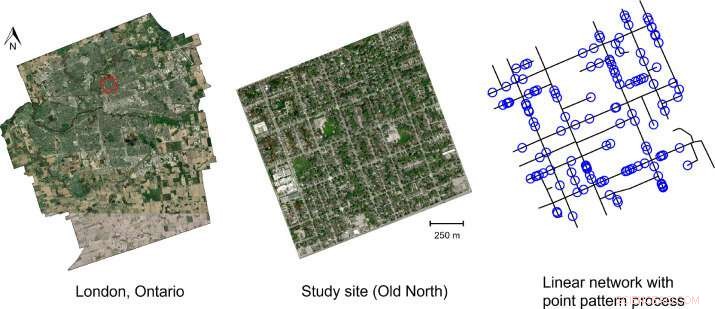

Links de gemeentegrenzen van Londen met gemarkeerd studiegebied, gelegen in Noord-Londen met de wijk Old North (afgebakend door de rode doos). Midden. Het studiegebied wordt begrensd door Richmond St. (in het westen), Adelaide St. (in het oosten), Huron St. (in het noorden) en Oxford St. (in het zuiden) en heeft een oppervlakte van ∼1,95 km 2 . Rechts. Geplande ruimtelijke verdeling van recyclingzakken binnen het studiegebied voor 2 maart 2021. Recyclingzakken worden weergegeven door blauwe locatiemarkeringen, zwarte lijnen geven het onderliggende lineaire netwerk aan dat is gevormd uit straten die zijn bemonsterd (exclusief de straten waar de inzameling al plaatsvond of was om logistieke redenen niet kunnen worden bemonsterd). Credit:Milieu-uitdagingen (2022). DOI:10.1016/j.envc.2022.100535

Biologieprofessor Paul Mensink leek een eenvoudige vraag:zijn plastic tassen die recyclebaar materiaal bevatten beter of slechter voor het milieu dan blauwe dozen?

Maar de vraag is een ingewikkeld raadsel geworden.

"Het korte antwoord is:'Het hangt ervan af'", zei Mensink, directeur van graduate milieuprogramma's aan de faculteit Bètawetenschappen, nadat zijn team een uitgebreide studie had gepubliceerd over het beleid en de praktijken van de gemeenten in Ontario voor het verzamelen en sorteren van recyclebaar materiaal.

Zijn onderzoek, gepubliceerd in Environmental Challenges , blijkt dat meer dan 40% van de gemeenten het gebruik van plastic recyclingzakken toestaat. Hij wilde de reden onderzoeken om tassen aan de stoeprand toe te staan of te verbieden.

"Het lijkt mij dat als je het een of het ander wilt toestaan of verbieden, je er goede wetenschap achter moet hebben. Ik wilde echt een solide antwoord krijgen over welke kant het op zou moeten gaan. En dat doen we gewoon niet weten."

Die dubbelzinnigheid zit Mensink niet lekker. Dat is een aanzienlijke kloof, zei hij, omdat de kosten van recycling, die nu 50/50 zijn verdeeld tussen industrie en gemeenten, binnenkort alleen door de industrie zullen worden gedragen.

In slechts één buurt ontdekte zijn team dat bijna één op de tien huizen minstens één plastic recyclingzak gebruikte, met een gemiddelde van 1,65 zakken per huis. Geëxtrapoleerd naar slechts 160 huishoudens, zou dat kunnen neerkomen op meer dan 10.000 recyclingzakken voor eenmalig gebruik per jaar, of ongeveer 380 kilogram plastic dat wordt gebruikt om plastic van de stortplaats te verwijderen. Als iedereen in Londen evenveel tassen zou gebruiken als deze ene buurt, zou dat neerkomen op 1,4 miljoen tassen per jaar.

Based on those numbers alone, Mensink was prepared to dismiss bags as environmental folly.

Until he and a team of environmental science students dug more deeply.

Some of the bags held shredded paper or easily dispersable plastics, they found. On windy days, the bags could prevent those items from becoming street litter as open-topped blue boxes couldn't.

Waste handlers can also pick up and sling bags into a recycling truck more quickly than they can sort through blue-box plastics and paper at curbside, and that can mean less tailpipe emissions.

On the other hand, there is the environmental cost of extracting the oil and manufacturing the bags in the first place, plus the cost of shipping them to a store and the cost a homeowner would have in driving to a store to buy them.

Then there's the question of what happens to the bags when they arrive at a recycling facility. Some municipalities have automatic debagging machines. At other facilities, someone has to rip them apart manually, at additional staffing costs and potential safety concerns for workers. Some facilities will send the bags back into the recycling stream, he found. At others, they are trashed.

"Initially I thought, 'Why use bags in the first place?' Single-use plastic bags sound like a bad idea because there are other, reusable options. However, when you take all the variables into account—it becomes a mind puzzle," Mensink said.

And if there's a single takeaway from their research so far, it would be that being environmentally responsible is a complex matter.

"I get that this is an overlooked issue, especially when our big aim here is to capture recyclables and keep them out of the landfill and waterways," said Mensink.

But consumption is costly. There is always a trade-off.

And calculating the true bottom line of any one solution always requires a deeper dive, he said. "Trying to measure the environmental impact of what we produce and consume is as complex as it is important."

Ontdekking van levensverlengingspad in wormen toont nieuwe manier om veroudering te bestuderen

Ontdekking van levensverlengingspad in wormen toont nieuwe manier om veroudering te bestuderen De kosten van ethanol verlagen, andere biobrandstoffen en benzine

De kosten van ethanol verlagen, andere biobrandstoffen en benzine De toekomst van elektronische apparaten:sterke en zelfherstellende iongels

De toekomst van elektronische apparaten:sterke en zelfherstellende iongels Ontdekking leidt tot nieuwe verouderingscrème en kippenvoer

Ontdekking leidt tot nieuwe verouderingscrème en kippenvoer Pandemiepreventie op luchthavens

Pandemiepreventie op luchthavens

Onderdelen van de waterkoeler kunnen een bron zijn van blootstelling aan organofosfaatesters

Onderdelen van de waterkoeler kunnen een bron zijn van blootstelling aan organofosfaatesters De bouwhausse in Florida bedreigt een lagune die rijk is aan wilde dieren

De bouwhausse in Florida bedreigt een lagune die rijk is aan wilde dieren Onderzoekers identificeren bacteriën en virussen die uit de oceaan zijn uitgestoten

Onderzoekers identificeren bacteriën en virussen die uit de oceaan zijn uitgestoten Bossen zijn de sleutel tot zoet water

Bossen zijn de sleutel tot zoet water Een droogte-index voor verdampingstekorten om de gevolgen van droogte voor ecosystemen te detecteren

Een droogte-index voor verdampingstekorten om de gevolgen van droogte voor ecosystemen te detecteren

Hoofdlijnen

- Welke invloed heeft CO2 op het openen van huidmondjes?

- Het unieke pentraxine-koolzuuranhydrase-eiwit reguleert het vermogen van vissen om te zwemmen

- Maakt Thanksgiving Turkije je echt slaperig?

Als je Thanksgiving-ritueel gepaard gaat met flauwvallen op de bank na een maaltijd, weet je al dat een feest met alles erop en eraan je moe maakt. Maar ondertekende de kalkoen je enkeltje naar snoozevil

- De Durian-industrie zou kunnen lijden zonder de bedreigde fruitvleermuis

- Hoe Agarose Gel te interpreteren

- Meer bewijs dat Neanderthalers niet dom waren:ze maakten hun eigen touwtje

- 'S Werelds oudste bevroren sperma werkt prima

- Suikerpoep kan worden gebruikt om destructieve plantenplagen naar hun ondergang te lokken

- Vrouwelijke fruitvliegjes betreden de ring van seksuele competitie

- Rhodoniet:een mineraal van liefde, rozen en adelaars

- Grootte is belangrijk voor beschermde mariene gebieden die zijn ontworpen om koraal te helpen

- Geowetenschappers vinden verklaring voor raadselachtige rotspartijen diep in de aardmantel

- In Israël, op zoek naar droogtes in het verleden en de toekomst

- Eerste luchtkwaliteitsprofiel van twee sub-Sahara Afrikaanse steden vindt verontrustend nieuws

Kronen van het bos:Indonesisch helpt orchideeën weer bloeien

Kronen van het bos:Indonesisch helpt orchideeën weer bloeien Eerste Israëlische nanosatelliet voor academisch onderzoek gelanceerd

Eerste Israëlische nanosatelliet voor academisch onderzoek gelanceerd Verre sterrenstelsels zijn in tegenspraak met gangbare kosmologische modellen, simulaties

Verre sterrenstelsels zijn in tegenspraak met gangbare kosmologische modellen, simulaties Dierlijke intelligentie en AI:de concurrentie zit in de coulissen

Dierlijke intelligentie en AI:de concurrentie zit in de coulissen Geweld tegen kinderen brengt enorme kosten met zich mee voor Afrika:regeringen moeten dringend optreden

Geweld tegen kinderen brengt enorme kosten met zich mee voor Afrika:regeringen moeten dringend optreden Wat gebeurt er wanneer Pepsin zich mengt met voedsel in de maag?

Wat gebeurt er wanneer Pepsin zich mengt met voedsel in de maag?  Met Astronomy Rewind, burgerwetenschappers brengen zombie-astrofoto's weer tot leven

Met Astronomy Rewind, burgerwetenschappers brengen zombie-astrofoto's weer tot leven Een oceaan van sterrenstelsels wacht:nieuwe COMAP-radio-enquête

Een oceaan van sterrenstelsels wacht:nieuwe COMAP-radio-enquête

- Elektronica

- Biologie

- Zonsverduistering

- Wiskunde

- French | Italian | Spanish | Portuguese | Swedish | German | Dutch | Danish | Norway |

-

Wetenschap © https://nl.scienceaq.com