Wetenschap

Fruitvliegen:zomerplagen of wetenschappelijk wonder?

Drosophila melanogaster. Krediet:Columbia's Zuckerman Institute

Het vliegmeppenseizoen is aangebroken. Nauwelijks zet je je verse aardbeien op het aanrecht of de eerste fruitvlieg arriveert. Het zal niet lang duren voordat een peloton van Drosophila-vrienden rond de buit zweeft.

Als je ervoor kiest om je insectendodende neigingen te meppen, swipen, meppen, backhanden of anderszins na te jagen, verspil dan geen leermoment. Het enige dat u hoeft te doen, is die tijdloze stelregel omarmen:ken uw vijand. Als hoofdbestanddeel van het laboratorium heeft de fruitvlieg bewezen een oneindige bron van biologische inspiratie en kennis te zijn over hoe de hersenen en het lichaam zich ontwikkelen en functioneren.

Les één:Fruitvliegen bestaan al langer dan wij, veel langer

Hoogstwaarschijnlijk zult u jammerlijk falen in uw ijver om uw interne fruitvliegjes af te weren. Het is niet dat je onbekwaam bent in het opstellen van je dodelijke slagen. Het is gewoon zo dat evolutie al zo'n 40 miljoen jaar de kleine hersenen, vleugels, sensorische systemen, spieren en interne organen van de vliegen aan het slijpen is in de kunst van het overleven. Dat is 38 miljoen jaar meer dan het ons als Homo sapiens heeft gekost om te evolueren van onze Australopithecus-voorouders. Fruitvliegen zitten al veel langer in de evolutieschool dan de mensheid.

Les twee:Fruitvliegen hebben een cultstatus in de wetenschap

In het begin van de 20e eeuw was Thomas Hunt Morgan van Columbia University een van de eerste onderzoekers die dit onwetende geschenk aan de wetenschap omarmden. In 1910 merkte Morgan dat hij gemakkelijk mutaties kon herkennen, zoals grote witte ogen in plaats van de gebruikelijke grote rode ogen van vliegen. Hij en zijn laboratoriumgenoten leerden hoe ze deze fysieke mutaties konden koppelen aan specifieke genetische stukken langs de chromosomen van de insecten.

Sindsdien zijn deze kleine geleedpotigen geliefde en onthullende onderzoekspartners gebleven. Voor veel van wat we weten over genetica, overerving, biologische ontwikkeling, sensorische wetenschap, vele ziekten en talloze andere facetten van de biologie, hebben we fruitvliegen te danken. Een recent onderzoek van de onderzoeksgemeenschap van fruitvliegen gaf aan dat een schatting van meer dan 6000 'vliegwerkers wereldwijd conservatief lijkt'.

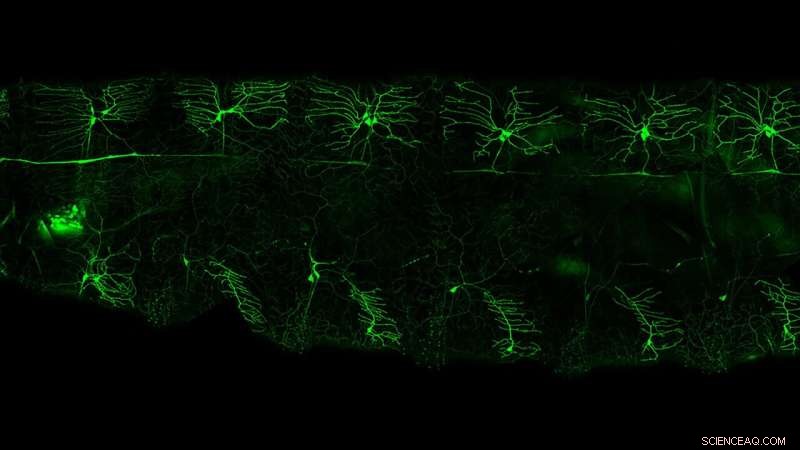

Fluorescerende labels onthullen sensorische cellen van een vliegenlarve. Krediet:Grueber Lab; Zuckerman Institute

Les drie:Fruitvliegjes zijn kleine Houdini's

Bij een dreiging kan een fruitvlieg vrijwel onmiddellijk reageren. To make basic evasive movements, the insect, even in its larval stages, has to keep precise track of where its body is in space. This body-place sense, common to all animals, is termed proprioception. It allows humans, for example, to know where their limbs are without looking directly at them and to make fine adjustments during any movement, such as reaching for a strawberry.

Wesley Grueber, Ph.D., and his colleagues at Columbia's Zuckerman Institute discovered that a collection of sensory cells in the fly allow it to keep precise track of where different body regions are located during movement.

Dr. Grueber points out that similar cells and circuits probably kick in when flies make those aeronautic escape sequences that have you cursing in the kitchen. That is, unless your deftly executed backhands squash the fleeing fruit flies, so that their previous and gorgeous marriage of form and function morphs into entropic functionless stains.

Lesson four:Fruit flies have 1,600 eyes, sort of

If you could pick through the aftermath of a swatted fruit fly's 580,000 or so cells, you would find at least some of the 800 light-harvesting facets, or ommatidia, that comprise each of a fly's eyes. You might also find remains of the 200,000 neurons that make up the fly's nervous system and thereby the circuitry it had used to see the world.

You would also be wandering into the territory of Rudy Behnia, Ph.D., a principal investigator at the Zuckerman Institute. Among other things, Dr. Behnia has been teasing out the cellular circuitry and computations that underlie fruit flies' color vision.

"Spectral information in the world is very rich and flies could use it for object recognition," as well as for determining the time of day and navigating with cues about the sun's location from the sky's color, Dr. Behnia says.

As is evident from your terrible batting average when it comes to fly-squishing, your insect nemeses know your murderous hand is coming. This intel derives from signal-delay circuitry built into the fruit fly's visual system. If the initial sensory signals change between ommatidia, as happens when your hand is sweeping through a fly's field of view, the resulting signal patterns deeper in the fly's brain carry information about the direction your hand is moving.

Now add in the fly's phototaxis, which plays into its knack for detecting and moving toward ultraviolet light, and you have the neurobiological foundation for an escape plan. "Since most objects in nature reflect rather than absorb ultraviolet radiation, the main source of natural UV is the open sky," Dr. Behnia explains. That means that if you are a fruit fly, and you detect ill will coming your way, you just need to follow that UV to the open sky.

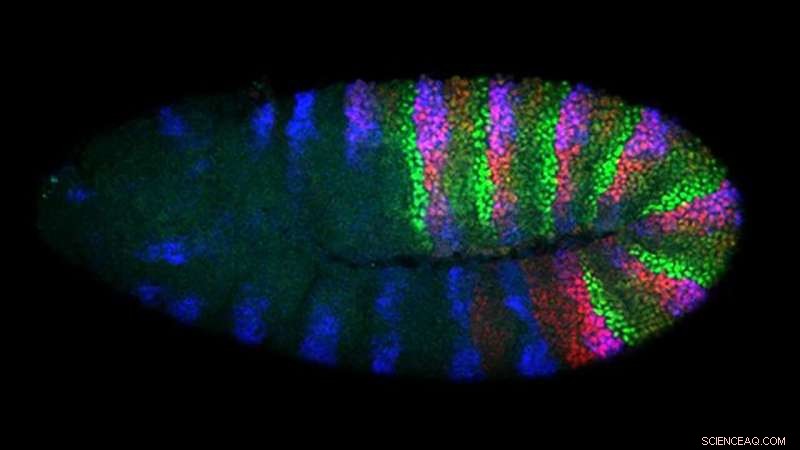

Fluorescent labels demarcate larval locations of specific Hox genes. Credit:Mann Lab; Zuckerman Institute

Lesson five:Fruit flies do mind-bending math, all in their heads

To plot their course through the world, and escape trajectories in times of peril, fruit flies use external reference points, such as the position of the sun, along with serious mental mathematics.

"The flies are doing trigonometry," says Larry Abbott, Ph.D., co-director of the Center for Theoretical Neuroscience at the Zuckerman Institute. "It's incredible."

A fly's mental computations start by representing vectors, mathematical arrows with angles and lengths that themselves represent the direction and speed of motion. Dr. Abbott and his colleagues discovered that the flies use wave-like patterns of brain activity to encode these vectors. The amplitudes and phases of those neural wave patterns match the lengths and angles of the corresponding vectors in actual space.

"Flies perform the types of vector calculations often assigned in introductory physics classes, but they do this in ways that are not typically taught in such courses," says Dr. Abbott, adding that he is looking forward to the arrival, later this summer, to a new colleague at the Zuckerman Institute, Dr. Gwyneth Card. She will investigate the neural circuitry flies use to decide exactly what escape response to enact, say, as a threatening human hand violates their personal space.

Lesson six:The same genes that grow humans grow flies

A fly contains half a million cells, distributed among more than 200 cell types and organized into body parts ranging from the antennae on the front of its head to the hairs on its posterior. This sophisticated body plan emerges from a fertilized egg thanks to a mere eight genes in the Hox family:the master conductors of development.

Over many years of investigations, Richard Mann, Ph.D., another Zuckerman neuroscientist who studies fruit flies, has been teasing out how Hox genes, transcription factors, and many other genes and proteins coordinate their fly-building feats according to a brilliant logic of biological development. What scientists learn about this logic in model organisms like fruit flies often points to analogous developmental logic in people, says Dr. Mann. He stresses that the genetic common ground for humans and fruit flies extends beyond development genes. Says Mann:"So many human genes are also found in flies and a majority of human disease genes are also found in flies."

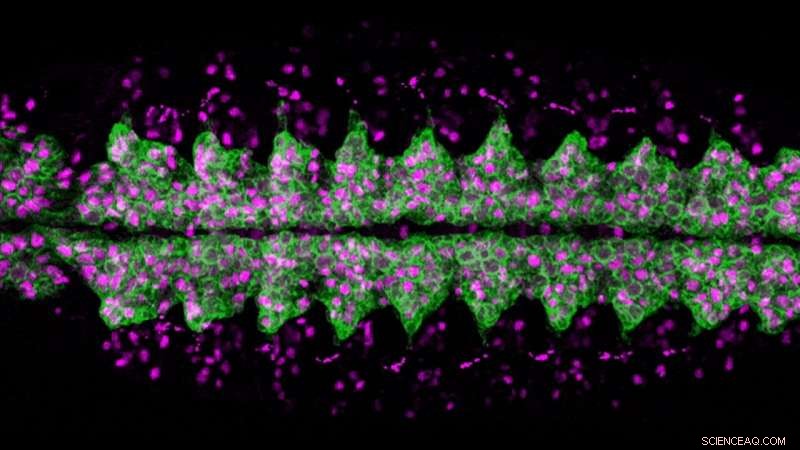

A green stain reveals neuroblasts, which are precursor cells that become neurons, specifically in the nerve cord of a fly embryo; the magenta stain lights up neuroblasts residing both within and without of the nerve cord. Credit:Kohwi Lab; Zuckerman Institute

Lesson seven:Fruit flies are symphonies of genetic and cellular notes

Extracting yet more biological insight from fruit fly genes is Zuckerman Institute principal investigator Minoree Kohwi, Ph.D.. She has been identifying the specific places and times in which development genes become active in sequential generations of cells of a growing fruit fly.

"Think of each gene as a single musical note:by itself, a note is an isolated sound, but play each note at the right time for just the right duration, and you get a beautiful symphony," Dr. Kohwi said.

One of the big questions she aims to answer is this:"How are the thousands of different cell types produced in such an organized manner to allow proper brain function?"

Dr. Kohwi's lab is uncovering the origins of a fly brain's many different cell types and thereby helping to reveal the origins of a similar diversity of cells in her own brain. Her research excavates deep into the molecular foundations of life by revealing how and when development genes migrate to different locations within a cell's nucleus. These migrations regulate when specific development genes are active and when they are repressed. And those on-off sequences, Dr. Kohwi says, "ultimately determine when each brain cell type can be made during development."

Squashing a miracle

Few Drosophila researchers would think twice about defending the fresh fruit on their tables with lethal force. But because of what they know about the marvels of fruit flies, you might see a flash of fly-admiration on their faces in the moment you hear thwap.

Wetenschappers maken gefermenteerd sap en functioneel brood om bloedarmoede te behandelen

Wetenschappers maken gefermenteerd sap en functioneel brood om bloedarmoede te behandelen Kooldioxide transformeren - onderzoekers ontwikkelen nieuwe tweestaps CO2-conversietechnologie

Kooldioxide transformeren - onderzoekers ontwikkelen nieuwe tweestaps CO2-conversietechnologie Minder verslavende opioïden ontwerpen door middel van chemie

Minder verslavende opioïden ontwerpen door middel van chemie Fluorine School Projects

Fluorine School Projects  Onderzoekers brengen kristallen in kaart om behandelingen voor beroerte te bevorderen, suikerziekte, Dementie

Onderzoekers brengen kristallen in kaart om behandelingen voor beroerte te bevorderen, suikerziekte, Dementie

Lijst met zoogdieren Native to MA

Lijst met zoogdieren Native to MA  George Monbiot Q + A - Hoe verjonging van de natuur de klimaatverandering kan helpen bestrijden

George Monbiot Q + A - Hoe verjonging van de natuur de klimaatverandering kan helpen bestrijden Indonesische aardbeving en tsunami verwoesten kust, veel slachtoffers

Indonesische aardbeving en tsunami verwoesten kust, veel slachtoffers Indonesië sluit 30 bedrijven af vanwege bosbranden

Indonesië sluit 30 bedrijven af vanwege bosbranden Centraal onderzoek ontdekt praktijken, technologieën sleutel tot duurzame landbouw

Centraal onderzoek ontdekt praktijken, technologieën sleutel tot duurzame landbouw

Hoofdlijnen

- Plantaardige hulpbronnen bedreigd door plagen en ziekten

- Hoe het Human Microbiome-project werkt

- Hoe jaarrond gewassen de vervuiling van de boerderij in de Mississippi-rivier kunnen verminderen

- Hoe diversifiëren en fylogenetisch correleren functionele eigenschappen voor co-voorkomende understory-soorten in boreale bossen?

- Krillgedrag brengt koolstof naar de diepten van de oceaan

- Wat zijn enkele veel voorkomende toepassingen van gist?

- The Bioteque:een computertool om biologische kennis te harmoniseren

- Hoe de vogels en de bijen koffieplanten helpen

- Orkaan legt duizenden zeeschildpadnesten bloot en spoelt ze weg

- Colombia wordt de eerste case study over hoe biodiversiteitsdoelstellingen in evenwicht kunnen worden gebracht met beperkte economische middelen

- Noorwegen zet hek op om rendierslachting te stoppen

- Wat maakt mensen gelukkiger -- objecten of ervaringen?

- Een nieuwe genetische bemonsteringstechniek voor kwelderoogstmuizen en andere kleine zoogdieren

- Nepal op schema om doel van verdubbeling tijgerpopulatie tegen 2022 te halen

Lockdown-critici zijn er zeker van dat de kosten opwegen tegen de gezondheidsvoordelen, maar ze hebben het mis

Lockdown-critici zijn er zeker van dat de kosten opwegen tegen de gezondheidsvoordelen, maar ze hebben het mis Een nieuwe classificatie van symmetriegroepen in de kristalruimte voorgesteld door Russische wetenschappers

Een nieuwe classificatie van symmetriegroepen in de kristalruimte voorgesteld door Russische wetenschappers Ouders van online gamers moeten twee keer nadenken voordat ze de hobby als tijdverspilling bestempelen

Ouders van online gamers moeten twee keer nadenken voordat ze de hobby als tijdverspilling bestempelen Ziektedragende muggen zeldzaam in ongestoorde tropische bossen

Ziektedragende muggen zeldzaam in ongestoorde tropische bossen McDonalds schakelt Alexa en Google in om te helpen bij het aannemen van personeel

McDonalds schakelt Alexa en Google in om te helpen bij het aannemen van personeel Galactische stervorming en superzware zwarte gatmassa's

Galactische stervorming en superzware zwarte gatmassa's De torsieconstante berekenen

De torsieconstante berekenen Internationale academische Santa-enquête toont aan dat kinderen op achtjarige leeftijd niet meer in de kerstman geloven

Internationale academische Santa-enquête toont aan dat kinderen op achtjarige leeftijd niet meer in de kerstman geloven

- Elektronica

- Biologie

- Zonsverduistering

- Wiskunde

- French | Italian | Spanish | Portuguese | Swedish | German | Dutch | Danish | Norway |

-

Wetenschap © https://nl.scienceaq.com