Wetenschap

Visgevechten:Groot-Brittannië heeft een lange geschiedenis van het verhandelen van toegang tot kustwateren

Een 19e-eeuwse Brixham trawler door William Adolphus Knell. Krediet:Nationaal Maritiem Museum/Wikipedia

De Britse boten werden door de Fransen met ongeveer acht overtroffen. Het duurde niet lang of er waren botsingen en er werden projectielen gegooid. De Britten moesten zich terugtrekken, terugkeren naar de haven met gebroken ramen maar gelukkig geen gewonden.

Het conflict achter deze schermutseling tussen Britse en Franse vissers in de Bay de Seine, eind augustus 2018, werd in de pers al snel de "schelpenoorlog" genoemd. De Fransen hadden geprobeerd te voorkomen dat de Britse sint-jakobsschelpen legaal op de bodem in de Franse nationale wateren zouden vissen. Maar het incident legde spanningen bloot die al jaren sudderen.

In het kader van het gemeenschappelijk visserijbeleid (GVB) van de Europese Unie, de Britse vissers hadden het wettelijke recht om in deze wateren te vissen, net als alle boten uit een EU-lidstaat. De complicatie kwam van een Franse regelgeving die lokale boten verhinderde om elk jaar tussen 16 mei en 30 september in deze wateren te vissen. om de voorraden te laten herstellen van de jaarlijkse oogst. Maar onder het GVB, een EU-land heeft geen bevoegdheid om te voorkomen dat de vloot van een andere lidstaat in zijn wateren vist.

Deze eigenaardigheid van het GVB zorgde ervoor dat de Franse vissers tot 1 oktober niet in staat waren om naar sint-jakobsschelpen te baggeren. en gedwongen toe te kijken terwijl vloten uit andere landen wat zij zagen als een Franse hulpbron uit Franse wateren oogstten. Toen de Britse boten arriveerden, de Franse vissers namen de rol op zich van bewakers van hun hulpbron, acties die volgens hen gerechtvaardigd waren, maar door de Britse visserijsector als illegaal werden beschouwd.

Dit incident in een klein hoekje van een gedeelde EU-zee werd binnen een paar weken geregeld dankzij een nieuwe overeenkomst over hoe de twee landen de coquille-oogst zouden verdelen. Maar de onderliggende spanningen die het GVB heeft veroorzaakt over het delen van nationale middelen gaan veel dieper, met het gevoel dat de regels een eerlijk gebruik van de zeeën niet toestaan.

Dit gevoel van oneerlijkheid kwam duidelijk tot uiting in de rol die de visserij speelde bij het besluit van Groot-Brittannië om de EU te verlaten. Campagnevoerders beloofden dat 'het terugnemen van de controle' over de Britse wateren het land in staat zou stellen zijn lang achterblijvende visserij-industrie en de gemeenschappen die ervan afhankelijk zijn, nieuw leven in te blazen.

Maar ongeacht de impact die het GVB heeft gehad op de Britse vissers, hun toekomst na de Brexit hangt sterk af van eventuele toekomstige handelsovereenkomsten die de regering met de EU onderhandelt. En de geschiedenis van hoe Groot-Brittannië heeft gereageerd op conflicten over visrechten die veel groter zijn dan de oorlog tegen sint-jakobsschelpen, belooft weinig goeds voor de industrie.

Het begin van de daling

Onderzoek naar visserijactiviteiten toont aan dat de achteruitgang van de Britse visserijsector begon lang voordat er enig Europees visserijbeleid werd ingevoerd. In feite, de uiteindelijke oorsprong is terug te voeren op een verrassende bron:de uitbreiding van de spoorwegen aan het einde van de 19e eeuw.

Trawlvisserij, onder de kracht van zeil, bestond al meer dan 500 jaar. Maar zonder koeling, vis kon alleen worden geleverd voor verkoop in gebieden dicht bij de havens. Door de komst van het spoorwegnet kon de vis het binnenland in naar grote steden.

Om verder aan deze groeiende vraag te voldoen, Vanaf de jaren 1880 begonnen stoomtrawlers de zeiltrawlers te vervangen. De kracht van deze stoomschepen vergroot de omvang van de trawlvisserij aanzienlijk en stelt hen in staat om langer en verder weg van de haven te vissen terwijl ze grotere netten trekken. Britse stoomtrawlers waagden zich verder weg van Groot-Brittannië op zoek naar vis, met de uitbreiding van de visgronden naar gebieden tot aan Groenland, Noord-Noorwegen en de Barentszzee, IJsland en de Faeröer.

Maar al in 1885 Er werd bezorgdheid geuit over het feit dat deze technologische vooruitgang een negatief effect zou hebben op zowel de visbestanden als hun leefgebied. Bewijs uit gegevens over visserijactiviteiten toont aan dat deze verbetering in technologie en de toegenomen omvang van de vissersvloot volledig achter de toename van de aanlandingen stonden.

De visserijhausse die de spoorwegen hadden ontketend bleek onhoudbaar, en de resulterende overbevissing zou de industrie uiteindelijk in een langdurige neergang brengen. Na decennia van steeds meer vissen, landingen begonnen uiteindelijk af te nemen na de Tweede Wereldoorlog, een trend die zich voortzette in de tweede helft van de 20e eeuw en in het nieuwe millennium.

Compenseren, de omvang en de kracht van de vloot bleven toenemen naarmate er meer inspanning nodig was om de steeds schaarser wordende vis te vangen. Vanaf eind jaren vijftig, de hoeveelheid aangevoerde vis per krachteenheid nam sneller af dan de aangevoerde vis, terwijl de vloot zich steeds meer inspande om de vangsten op peil te houden. Echter, deze inspanning was allemaal tevergeefs en in 1980 waren de vangsten gedaald tot het laagste punt in een eeuw.

De IJslandse Odinn en HMS Scylla botsen in de Noord-Atlantische Oceaan tijdens de 'Derde Kabeljauwoorlog' in de jaren zeventig. Krediet:Isaac Newton/www.hmsbacchante.co.uk

Kabeljauwoorlogen

Overbevissing was niet de enige reden voor achteruitgang, echter. De dalende visbestanden in combinatie met de verbeteringen in het bereik en de kracht van de vloot in de naoorlogse jaren leidden ertoe dat de vissers van Groot-Brittannië nieuwe wateren zochten, met meer boten die verder van het VK wegtrekken om genoeg vis te vangen om aan de binnenlandse vraag te voldoen. En deze lange afstand trawlvisserij bracht de Britse vloot in conflict met IJsland.

Vanaf de 15e eeuw hadden Britse vissers deze wateren bevist. Echter, De visserij-industrie van IJsland begon dit kwalijk te nemen toen de stoomtrawlers aan het einde van de 19e eeuw voor de kust van IJsland begonnen te vissen. Het leidde tot beschuldigingen dat Britse trawlers de visgronden zouden beschadigen en de bestanden zouden uitputten. In 1952, IJsland heeft een gebied van vier mijl rond hun land uitgeroepen om een einde te maken aan buitensporige buitenlandse visserij, hoewel vissen zich niet aan door mensen gemaakte grenzen houden en de bestanden buiten deze zone nog steeds uitgeput kunnen raken. Het besluit van IJsland trok een reactie van het VK, die de invoer van IJslandse vis verbood. Als belangrijke exportmarkt voor IJslands belangrijkste industrie hoopten ze dat dit hen aan de onderhandelingstafel zou brengen.

1958, tegen een achtergrond van mislukte diplomatie, IJsland breidde deze zone uit tot 12 mijl en verbood buitenlandse vloten om in deze wateren te vissen, in strijd met het internationaal recht. Het leidde tot de eerste van wat bekend werd als de Cod Wars - een act in drie fasen die bijna 20 jaar duurde.

Tijdens de eerste kabeljauwoorlog Fregatten van de Royal Navy vergezelden de Britse vloot naar de uitsluitingszone van IJsland om hun visserij voort te zetten. Er ontstond een kat-en-muisspel tussen de IJslandse kustwachtschepen en de Britse trawlers. In reactie op pogingen om ze te grijpen, de trawlers ramden de kustwachtschepen en de kustwacht dreigde het vuur te openen, hoewel grote incidenten werden vermeden.

1961, de twee landen kwamen uiteindelijk tot een overeenkomst waardoor IJsland zijn 12-mijlszone mocht behouden. In ruil, het VK kreeg voorwaardelijke toegang tot deze wateren.

tegen 1972, echter, overbevissing buiten deze limiet was verergerd en IJsland breidde zijn exclusieve zone uit tot 80 mijl en vervolgens drie jaar later, tot 200 mijl. Beide bewegingen leidden tot meer botsingen tussen IJslandse trawlers en de escorteschepen van de Royal Navy. respectievelijk de tweede en derde kabeljauwoorlog genoemd.

Schepen van de IJslandse kustwacht sleepten apparaten die waren ontworpen om de stalen trawldraden (trossen) van de Britse trawlers door te snijden - en schepen van alle kanten waren betrokken bij opzettelijke aanvaringen. Hoewel deze botsingen voornamelijk bloedeloos waren, a British fisher was seriously injured when he was hit by a severed hawser and an Icelandic engineer died while repairing damage to a trawler that had clashed with a Royal Navy frigate.

In January 1976, British naval frigate HMS Andromeda collided with Thor, an Icelandic gunboat, which also sustained a hole in its hull. While British officials called the collision a "deliberate attack", the Icelandic Coastguard accused the Andomeda of ramming Thor by overtaking and then changing course. Eventually NATO intervened and another agreement was reached in May 1976 over UK access and catch limits. This agreement gave 30 vessels access to Iceland's waters for six months.

NATO's involvement in the dispute had little to do with fisheries and a large amount to do with the Cold War. Iceland was a member of NATO, and therefore aligned to the US, with a substantial US military presence in Iceland at the time. Iceland believed that NATO should intervene in the dispute but it had up until that point resisted. Popular feeling against NATO grew in Iceland and the US became concerned that this strategically important island nation – which allowed control of the Greenland Iceland UK (GIUK) gap, an anti-submarine choke point – could leave NATO and worse, align itself with the Soviets.

Amid protests at the US military base in Iceland demanding the expulsion of the Americans, and growing calls from Icelandic politicians that they should leave NATO, the US put pressure on the British to concede in order to protect the NATO alliance. The agreement brought to an end more than 500 years of unrestricted British fishing in these waters.

The loss of these Atlantic fishing grounds cost 1, 500 jobs in the home ports of the UK's distant water fleet, concentrated around Scotland and the north-east of England, with many more jobs lost in shore-based support industries. This had a significant negative impact on the fishing communities in these areas.

The UK also established its own 200-mile limit in response to Iceland's exclusion zone. These limits were eventually incorporated in the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, giving similar rights to every sovereign nation. The creation of these "exclusive economic zones" (EEZ) was the first time that the international community had recognised that nations could own all of the resources that existed within the seas that surrounded them and exclude other nations from exploiting these resources.

The UK now owned the rights to the 200-mile zone around its islands, which contained some of the richest fishing grounds in Europe but up until this point the principle of "open seas" had existed, with Britain its most vocal champion. Fishing nations, had fished the high seas within 200 miles of their own and others coasts for centuries and now were restricted to their own.

British trawler Coventry City passes Icelandic Coastguard patrol vessel Albert off the Westfjords in 1958 during the first Cod War. Credit:Kjallakr/Wikipedia

Economic trade offs

Britain's Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), echter, wasn't that exclusive.

On joining the European Economic Community (the forerunner to the EU) in 1972, the UK had agreed to a policy of sharing access to its waters with all member states, and gaining access to the waters of other countries in return. The UN convention effectively gave the EEC one giant EEZ.

The UK government was willing to enter into the agreement as fisheries were one part of overall negotiations that would allow the UK to export goods and services to the European continent with significantly reduced trade barriers.

Although the fishing industry is of high local importance to fishing communities, it is relatively unimportant to the UK economy as a whole. in 2016, the UK fishing industry (which includes the catching sector and all associated industries) was valued at £1.6 billion, against £1.76 trillion for the UK economy as a whole – or just under 1%. The UK's trade with the EU, both import and export, stands at £615 billion a year in comparison.

Enter the Common Fisheries Policy

In 1983, the Common Fisheries Policy was adopted, introducing management of European waters by giving each state a quota for what it could catch, based on a pre-determined percentage of total fishing opportunities. This was known as "relative stability" and was based on each country's historic fishing activity before 1983, which still determines how quotas are allocated today.

The formula that the EEC adopted, based on historic catches, is one of most contentious parts of the CFP for the UK. Many fishers have stories of the years running up to 1983, where foreign vessels increased their fishing activity in UK waters in order to secure a larger share of these fish in perpetuity. Although there is little evidence to support these views, it demonstrates the level of distrust in both the system, and foreign fishers, from the outset.

Als resultaat, only 32% of fish caught in the UK EEZ today is caught by UK boats, with most of the remainder taken by vessels from other EU states, Norway and the Faroe Islands (who have also joined the CFP). Daarom, non-UK vessels catch the remaining 68%, about 700, 000 tonnes, of fish a year in the UK EEZ.In return, the UK fleet lands about 92, 000 tonnes a year from other EU countries' waters.

Joining the CFP did not cause a decline in UK fish landings. Echter, in zijn begindagen, it did nothing to stop it. Fish landings continued to decline – and along with this, the industry itself contracted, using improved technology to offset the decline in stocks. Through the 1980s and into the early part of this century the imbalance – enshrined in the relative stability measure of the CFP – has led to the view that the CFP doesn't work in the UK's interests. Rather it allows the rest of the EU to take advantage of the country's fish stocks.

The CFP's quota system, while credited for helping the industry survive (and even reverse the collapse in fish stocks), is now seen as burdensome and preventing further growth.

A recent academic analysis of the current performance of the CFP showed it was not improving the management of the fish stock resources in any of its 17 criteria and was actually making things worse in seven areas.

Bijvoorbeeld, a 2013 reform of the CFP introduced the landing obligation, the so-called "discard ban", that was designed to stop vessels discarding fish (bycatch) caught alongside the species they were targeting. Environmentalists, and campaigns backed by celebrities such as Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall, have long voiced concerns over incidents of bycatch being dumped by fishers operating under the quota system.

This policy is now seen as potentially disastrous by some representatives of Britain's North Sea fishing fleet, as so many different types of fish live in the waters and bycatch is common and often unavoidable. They are concerned that boats would be forced to fill their holds with commercially worthless fish and return to port early. Or by exhausting their quota for some species early in the season, they would be forced to stay in port for the rest of the year, despite having quotas available for other species. Evidence given to the House of Lords suggests that this situation has not arisen as non-compliance and a lack of enforcement has undermined the discard ban.

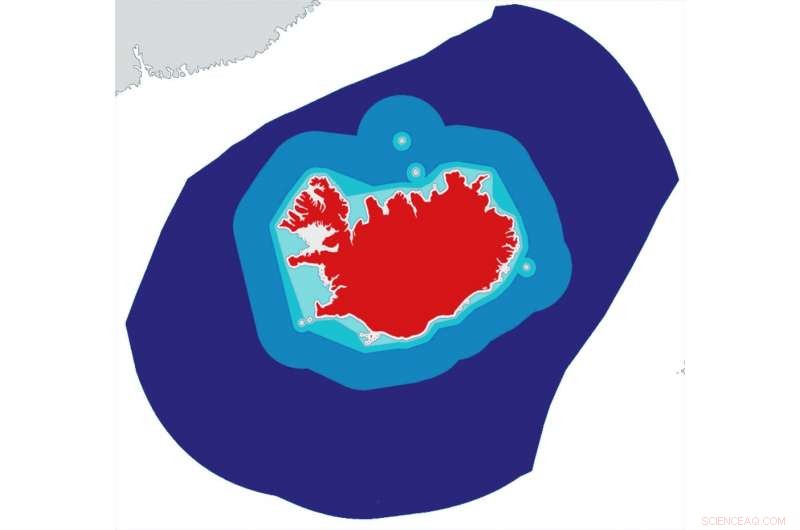

Map of the Icelandic EEZ, and its expansion. Red =Iceland. White =internal waters. Light turquoise =four-mile expansion, 1952. Dark turquoise =12-mile expansion (current extent of territorial waters), 1958. Blue =50-mile expansion, 1972. Dark blue =200-mile expansion (current extent of EEZ), 1975. Credit:Kjallakr/Wikipedia, CC BY-SA

When we interviewed fishers in north-east Scotland in 2018, we found many feared such blanket management across the entire EU would continue to damage their industry because it simply does not take into account the local environment that they work in.

Brexit

The depth of feeling among the UK fishing community was illustrated by the voting figures for the EU referendum in June 2016.

In Banff and Buchan, the constituency in Scotland containing Peterhead and Fraserburgh – the largest and third largest fishing ports in the UK respectively – 54% of people voted to leave the EU, with the size of the fishing industry given as the reason for this result. The result compared to 52% for the whole of the UK and just 38% for Scotland. A survey of members of the UK fishing industry before the vote indicated that 92.8% of correspondents believed that doing so would improve the UK fishing industry by some measure.

But will Brexit really bring the fishing revival so many have promised and hoped for? British politicians have promised a renaissance in UK fishing after leaving the EU. A Fisheries Bill was launched by the environment secretary, Michael Gove, with an aim to "take back control of UK waters". Echter, no definitive plan to remove the UK from the CFP in a transition deal has been made, nor has the industry been given any answers on future access for EU vessels, the apportionment of any new quota – if indeed the quota system remains as it is – the rules that they will be operating under, or even a date on which this will come into effect.

The UK government is seen by many in the fishing industry to be acting against their interests in pursuit of wider goals, for example by using the industry as a bargaining chip in wider UK trade negotiations with the EU.

The fishing industry's distrust of the government has a long tail:many believe they were sacrificed in 1973 by the then prime minister, Edward Heath, in order to secure access to the single market.

A soured relationship

Ironisch, despite the fishing industry's support for Brexit and the popular campaign promises, our research suggests fishers don't simply want to close British waters to European fleets. We interviewed people who were sympathetic to their fellow fishers from abroad and did not wish to see businesses and livelihoods lost. They favour a re-balancing of quotas over time to allow EU vessels to adapt to the change, with all vessels having to adhere to UK rules. This would avoid any situations similar to the Scallop War by ensuring that all vessels with a quota have to abide by local restrictions.

The EU is the main export market for UK fish and fisheries products accounting for 70% of UK fisheries exports by value. Valued at £1.3 billion, this trade far exceeds the £980m value of fish landed in the UK, due to the added value from the processing sector. Some of the remaining 30% of exports that go to countries outside of the EU are governed by trade agreements negotiated by the EU that reduce trade barriers. So the single market, and additional trade agreements, are crucial to the success of the UK fishing industry.

This reliance on trade into the EU puts the industry in a position where unilaterally preventing access to UK waters would likely be met by reciprocal trade barriers and tariffs. This would increase the cost of their product, while reducing access to their biggest market. The question for the government, dan, is how to balance a political issue against an economic one?

The issue centres on the word "control". If the UK has control of its waters that would simply mean that its government has the power to decide on anything from keeping fishing within UK waters purely for UK vessels, to remaining in or re-entering the CFP, or all points in between. Until the deals are negotiated and signed, the industry will remain in a limbo that has reopened old wounds and reignited distrust in the UK government.

Dit artikel is opnieuw gepubliceerd vanuit The Conversation onder een Creative Commons-licentie. Lees het originele artikel.

Studie werpt licht op de samenstelling van stof dat door regenwater door Texas wordt gedragen

Studie werpt licht op de samenstelling van stof dat door regenwater door Texas wordt gedragen Vier soorten regen

Vier soorten regen Afbeelding:Stormjager in actie

Afbeelding:Stormjager in actie Onderzoekers vinden stortplaats onder water terwijl ze op zoek zijn naar chemische lozingen van elektronische apparaten

Onderzoekers vinden stortplaats onder water terwijl ze op zoek zijn naar chemische lozingen van elektronische apparaten Nieuw platform voor risicotriage lokaliseert toenemende bedreigingen voor de Amerikaanse infrastructuur

Nieuw platform voor risicotriage lokaliseert toenemende bedreigingen voor de Amerikaanse infrastructuur

Hoofdlijnen

- Hoe kunnen botten bloedcellen aanmaken?

- Het herprogrammeren van bacteriën in plaats van ze te doden kan het antwoord zijn op antibioticaresistentie

- Kan slapen met een hersenschudding je doden?

- Kleine Braziliaanse kikkers zijn doof voor hun eigen roep

- EU-parlement stemt voor verbod controversiële onkruidverdelger in 2022

- Bioreactoren op een chip vernieuwen beloften voor algenbiobrandstoffen

- Een incubator laten groeien Bacteriën

- Zijn mannen of vrouwen gelukkiger?

- De verschillen tussen Catecholamines en Cortisol

- Kan Googles Sergey Brin helpen de komende luchtschiprevolutie te versnellen?

- Nieuwpoort 17

- Hoge energierekeningen kunnen gezinnen tot armoede leiden, landelijke studie toont

- Religie speelde een belangrijke rol bij de stemming van Groot-Brittannië om de EU te verlaten in 2016, uit onderzoek blijkt

- Onderzoek van de business school is kapot - hier is hoe het te repareren

Magnetiet nanodraden met scherpe isolerende overgang

Magnetiet nanodraden met scherpe isolerende overgang Oud botbeeldhouwwerk kan de manier waarop we over Neanderthalers denken veranderen

Oud botbeeldhouwwerk kan de manier waarop we over Neanderthalers denken veranderen Racisme is nog steeds een enorm probleem op de Britse werkplekken, vindt rapport

Racisme is nog steeds een enorm probleem op de Britse werkplekken, vindt rapport Poolse dagbladen drukken blanco voorpagina in beroep op EU-auteursrecht

Poolse dagbladen drukken blanco voorpagina in beroep op EU-auteursrecht Rassendiscriminatie kan de cognitie bij Afro-Amerikanen negatief beïnvloeden

Rassendiscriminatie kan de cognitie bij Afro-Amerikanen negatief beïnvloeden Vijf manieren waarop kunst kan helpen de plasticcrisis op te lossen

Vijf manieren waarop kunst kan helpen de plasticcrisis op te lossen VN start grote inspanningen op het gebied van klimaatverandering

VN start grote inspanningen op het gebied van klimaatverandering Wat zijn de voor- en nadelen van elektromagnetische energiebronnen?

Wat zijn de voor- en nadelen van elektromagnetische energiebronnen?

- Elektronica

- Biologie

- Zonsverduistering

- Wiskunde

- French | Italian | Swedish | German | Dutch | Danish | Norway | Spanish | Portuguese |

-

Wetenschap © https://nl.scienceaq.com