Wetenschap

Wat de explosie van uraniumprijzen betekent voor de nucleaire industrie

Ga goed naar achteren staan. Credit:RHJPhtotoandilustration

Het is een jaar geleden dat Horizon Nuclear Power, een bedrijf dat eigendom is van Hitachi, heeft bevestigd dat het zich terugtrekt uit de bouw van de Wylfa-kerncentrale van £ 20 miljard in Anglesey in Noord-Wales. Het Japanse industriële conglomeraat noemde het falen om een financieringsovereenkomst met de Britse regering te bereiken over stijgende kosten, en de regering is nog in onderhandeling met andere spelers om te proberen het project vooruit te helpen.

De aandelenkoers van Hitachi steeg met 10% toen het zijn terugtrekking aankondigde, wat een weerspiegeling is van het negatieve sentiment van beleggers ten aanzien van het bouwen van complexe, sterk gereguleerde grote kerncentrales. Nu regeringen terughoudend zijn met het subsidiëren van kernenergie vanwege de hoge kosten, vooral sinds de ramp in Fukushima in 2011, heeft de markt het potentieel van deze technologie om de noodsituatie in het klimaat aan te pakken, onderschat door overvloedige en betrouwbare koolstofarme elektriciteit te leveren.

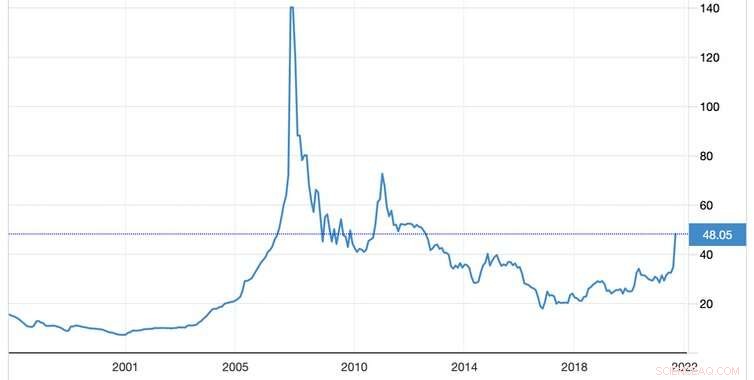

De uraniumprijzen hebben lang deze realiteit weerspiegeld. De primaire brandstof voor kerncentrales gleed gedurende een groot deel van de jaren 2010 af, zonder tekenen van een grote ommekeer. Maar sinds half augustus zijn de prijzen met ongeveer 60% gestegen, terwijl investeerders en speculanten zich inspannen om de grondstof in handen te krijgen. De prijs ligt rond de $ 48 per pond (453 g), op 16 augustus nog zo goedkoop als $ 28,99. Dus wat zit er achter deze rally en wat betekent het voor kernenergie?

Uraniumprijs

De uraniummarkt

De vraag naar uranium is beperkt tot de productie van kernenergie en medische apparatuur. De jaarlijkse wereldwijde vraag is 150 miljoen pond, waarbij kerncentrales contracten willen sluiten die ongeveer twee jaar voor gebruik worden afgesloten.

Hoewel de vraag naar uranium niet immuun is voor economische neergang, is deze minder kwetsbaar dan andere industriële metalen en grondstoffen. Het grootste deel van de vraag is verdeeld over zo'n 445 kerncentrales die actief zijn in 32 landen, en het aanbod is geconcentreerd in een handvol mijnen. Kazachstan is gemakkelijk de grootste producent met meer dan 40% van de productie, gevolgd door Australië (13%) en Namibië (11%).

Aangezien het meeste gewonnen uranium door kerncentrales als brandstof wordt gebruikt, is de intrinsieke waarde ervan nauw verbonden met zowel de huidige vraag als het toekomstige potentieel van deze industrie. De markt omvat niet alleen uraniumconsumenten, maar ook speculanten, die kopen wanneer ze denken dat de prijs goedkoop is, en mogelijk de prijs verhogen. Een van die langetermijnspeculanten is de in Toronto gevestigde Sprott Physical Uranium Trust, die de afgelopen weken bijna 6 miljoen pond (of 240 miljoen dollar) uranium heeft gekocht.

Waarom het optimisme van beleggers kan toenemen

Hoewel algemeen wordt aangenomen dat kernenergie een integrale rol moet spelen in de transitie naar schone energie, hebben de hoge kosten ervoor gezorgd dat het niet concurrerend is in vergelijking met andere energiebronnen. Maar dankzij scherpe stijgingen van de energieprijzen verbetert de concurrentiekracht van kernenergie. We zien ook een grotere betrokkenheid bij nieuwe kerncentrales uit China en elders. Meanwhile, innovative nuclear technologies such as small modular reactors (SMRs), which are being developed in countries including China, the US, UK and Poland, promise to reduce upfront capital costs.

Credit:Trading Economics

Combined with recent optimistic releases about nuclear power from the World Nuclear Association and the International Atomic Energy Agency (the IAEA upped its projections for future nuclear-power use for the first time since Fukushima) this is all making investors more bullish about future uranium demand.

The effect on the price has also been multiplied by issues on the supply side. Due to the previously low prices, uranium mines around the world have been mothballed for several years. For example, Cameco, the world's largest listed uranium company, suspended production at its McArthur River mine in Canada in 2018.

Global supply was further hit by COVID-19, with production falling by 9.2% in 2020 as mining was disrupted. At the same time, since uranium has no direct substitute, and is involved with national security, several countries including China, India and the US have amassed large stockpiles—further limiting available supply.

Hang on tight

When you compare the cost of producing electricity over the lifetime of a power station, the cost of uranium has a much smaller impact on a nuclear plant than the equivalent effect of, say, gas or biomass:it's 5% compared to around 80% in the others. As such, a big rise in the price of uranium will not massively affect the economics of nuclear power.

Yet there is certainly a risk of turbulence in this market over the months ahead. In 2021, markets for the likes of Gamestop and NFTs have become iconic examples of speculative interest and irrational exuberance—optimism driven by mania rather than a sober evaluation of the economic fundamentals.

The uranium price surge also appears to be catching the attention of transient investors. There are indications that shares in companies and funds (like Sprott) exposed to uranium are becoming meme stocks for the r/WallStreetBets community on Reddit. Irrational exuberance may not have explained the initial surge in uranium prices, but it may mean more volatility to come.

We could therefore see a bubble in the uranium market, and don't be surprised if it is followed by an over-correction to the downside. Because of the growing view that the world will need significantly more uranium for more nuclear power, this will likely incentivise increased mining and the release of existing reserves to the market. In the same way as supply issues have exacerbated the effect of heightened demand on the price, the same thing could happen in the opposite direction when more supply becomes available.

You can think of all this as symptomatic of the current stage in the uranium production cycle:a glut of reserves has suppressed prices too low to justify extensive mining, and this is being followed by a price surge which will incentivise more mining. The current rally may therefore act as a vital step to ensuring the next phase of the nuclear power industry is adequately fuelled.

Amateur traders should be careful not to get caught on the wrong side of this shift. But for a metal with a half life of 700 million years, serious investors can perhaps afford to wait it out.

Het identificeren van designer medicijnen die worden ingenomen door patiënten met een overdosis

Het identificeren van designer medicijnen die worden ingenomen door patiënten met een overdosis Eenstapskatalysator zet nitraten om in water en lucht

Eenstapskatalysator zet nitraten om in water en lucht De nieuwste magnesiumstudies maken de weg vrij voor nieuwe biomedische materialen

De nieuwste magnesiumstudies maken de weg vrij voor nieuwe biomedische materialen Antikankermechanisme onthuld in gistexperimenten

Antikankermechanisme onthuld in gistexperimenten Jodium extraheren uit kalium Jodide

Jodium extraheren uit kalium Jodide

Studie zegt dat blauwe waterstof waarschijnlijk slecht is voor het klimaat

Studie zegt dat blauwe waterstof waarschijnlijk slecht is voor het klimaat Omgaan met klimaatstress op Antarctica

Omgaan met klimaatstress op Antarctica Nederlanders versterken grote dijk als zeeën stijgen, klimaat veranderingen

Nederlanders versterken grote dijk als zeeën stijgen, klimaat veranderingen Een wending in het verhaal van vulkaanuitbarstingen en massa-extincties

Een wending in het verhaal van vulkaanuitbarstingen en massa-extincties Geografen maken een ijsdiktekaart van Spitsbergen

Geografen maken een ijsdiktekaart van Spitsbergen

Hoofdlijnen

- DNA-replicatie vergelijken en contrasteren in prokaryoten en eukaryoten

- Parasieten van huisdieren die dieren in het wild wereldwijd aantasten

- Bereidheid om risico's te nemen - een persoonlijkheidskenmerk

- Oorsmeer zoals ijskernen - ontsluiten het verleden verborgen in oordopjes voor walvissen

- Hoe bevers nat blijven tijdens droogte in het VK

- Biologen pakken wereldwijde uitstervingscrisis aan

- Wat zijn organellen in een prokaryotische cel?

- Nieuwe vliegsoort in Central Park krijgt bijnaam CCNY-professoren

- Nieuw algoritme herkent duidelijke dolfijnklikken in onderwateropnamen

- Amazon verhoogt verkoperskosten voor vakanties tegen stijgende kosten

- Singapore keurt nepnieuwswet goed ondanks felle kritiek

- Laten we niet gaan! Nintendo wint rechtszaak in Japan over straatkarting met Mario

- Britse huishoudens steunen een terugkeer naar waterstof als huisbrandstof

- Videogame Death Stranding biedt nieuwe hoop

Atoombeeld van de verbazingwekkende moleculaire machines van de natuur aan het werk

Atoombeeld van de verbazingwekkende moleculaire machines van de natuur aan het werk Modelleren hoe dunne films uiteenvallen

Modelleren hoe dunne films uiteenvallen Instagram onthult nieuwe videoservice als uitdaging voor YouTube

Instagram onthult nieuwe videoservice als uitdaging voor YouTube Dreigende crisis van de sterk verminderde zoetwatervoorziening naar de Nijldelta van Egypte

Dreigende crisis van de sterk verminderde zoetwatervoorziening naar de Nijldelta van Egypte Onderzoekers gebruiken AI om prioriteitsgebieden te definiëren voor actie om ontbossing in de Amazone tegen te gaan

Onderzoekers gebruiken AI om prioriteitsgebieden te definiëren voor actie om ontbossing in de Amazone tegen te gaan Fagen gebruiken om nieuwe antivries-eiwitten te ontdekken

Fagen gebruiken om nieuwe antivries-eiwitten te ontdekken EU lanceert diepgaand onderzoek naar Amazon over datagebruik

EU lanceert diepgaand onderzoek naar Amazon over datagebruik Met een daling van LA's vervuiling door aerosolen, vegetatie komt naar voren als belangrijke bron

Met een daling van LA's vervuiling door aerosolen, vegetatie komt naar voren als belangrijke bron

- Elektronica

- Biologie

- Zonsverduistering

- Wiskunde

- French | Italian | Spanish | Portuguese | Swedish | German | Dutch | Danish | Norway |

-

Wetenschap © https://nl.scienceaq.com