Wetenschap

Er zijn niet genoeg bomen in de wereld om de koolstofemissies van de samenleving te compenseren - en die zullen er nooit zijn

Een tropisch regenwoud in Zuid-Amerika. Krediet:Shutterstock/BorneoRimbawan

Op een ochtend in 2009 Ik zat in een krakende bus die zich een weg baande tegen een berghelling in centraal Costa Rica, licht in mijn hoofd van dieseldampen terwijl ik mijn vele koffers vasthield. Ze bevatten duizenden reageerbuisjes en monsterflesjes, een tandenborstel, een waterdicht notitieboekje en twee kledingwissels.

Ik was op weg naar La Selva Biologisch Station, waar ik enkele maanden zou doorbrengen met het bestuderen van de natte, reactie van laaglandregenwoud op steeds vaker voorkomende droogtes. Aan weerszijden van de smalle snelweg, bomen bloedden in de mist als aquarellen in papier, waardoor de indruk ontstaat van een oneindig oerbos badend in wolken.

Terwijl ik uit het raam staarde naar het imposante landschap, Ik vroeg me af hoe ik ooit had kunnen hopen een landschap zo complex te begrijpen. Ik wist dat duizenden onderzoekers over de hele wereld met dezelfde vragen worstelden, proberen het lot van tropische bossen in een snel veranderende wereld te begrijpen.

Onze samenleving vraagt zoveel van deze kwetsbare ecosystemen, die de zoetwaterbeschikbaarheid voor miljoenen mensen regelen en de thuisbasis zijn van twee derde van de terrestrische biodiversiteit van de planeet. En steeds meer, we hebben een nieuwe eis gesteld aan deze bossen - om ons te redden van door de mens veroorzaakte klimaatverandering.

Planten nemen CO . op 2 uit de atmosfeer, verandert het in bladeren, hout en wortels. Dit alledaagse wonder heeft de hoop gewekt dat planten, met name snelgroeiende tropische bomen, kunnen fungeren als een natuurlijke rem op klimaatverandering, het opvangen van een groot deel van de CO 2 uitgestoten door verbranding van fossiele brandstoffen. Over de wereld, regeringen, bedrijven en liefdadigheidsinstellingen voor natuurbehoud hebben toegezegd enorme aantallen bomen te behouden of te planten.

Maar het feit is dat er niet genoeg bomen zijn om de koolstofemissies van de samenleving te compenseren - en die zullen er ook nooit zijn. Ik heb onlangs een overzicht gemaakt van de beschikbare wetenschappelijke literatuur om te beoordelen hoeveel koolstofbossen haalbaar zouden kunnen zijn. Als we absoluut de hoeveelheid vegetatie zouden maximaliseren die al het land op aarde zou kunnen bevatten, we zouden genoeg koolstof vastleggen om de uitstoot van ongeveer tien jaar broeikasgassen tegen de huidige tarieven te compenseren. Daarna, er zou geen verdere toename van koolstofafvang kunnen zijn.

Toch is het lot van onze soort onlosmakelijk verbonden met het voortbestaan van bossen en de biodiversiteit die ze bevatten. Door zich te haasten om miljoenen bomen te planten voor het opvangen van koolstof, zouden we onbedoeld de boseigendommen kunnen beschadigen die ze zo belangrijk maken voor ons welzijn? Om deze vraag te beantwoorden, we moeten niet alleen nadenken over hoe planten CO . opnemen 2 , maar ook hoe ze zorgen voor de stevige groene basis voor ecosystemen op het land.

Hoe planten klimaatverandering bestrijden

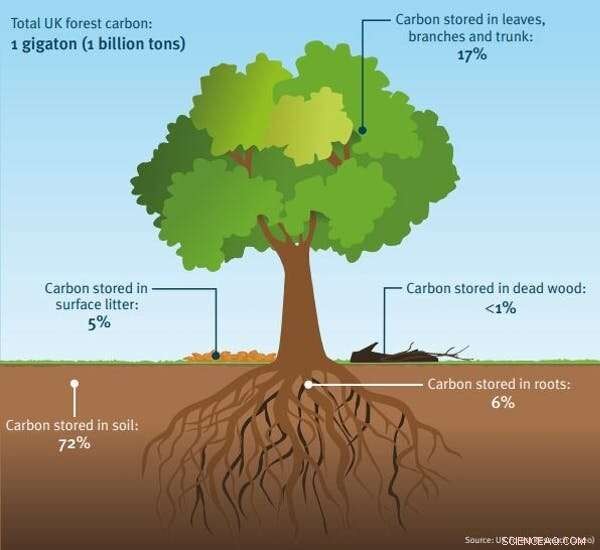

Planten zetten CO . om 2 gas in eenvoudige suikers in een proces dat bekend staat als fotosynthese. Deze suikers worden vervolgens gebruikt om de levende lichamen van de planten op te bouwen. Als de opgevangen koolstof in hout terechtkomt, het kan tientallen jaren van de atmosfeer worden afgesloten. Als planten sterven, hun weefsels ondergaan verval en worden opgenomen in de bodem.

Bonnie Waring doet onderzoek op La Selva Biological Station, Costa Rica, 2011. Auteur verstrekt

Terwijl bij dit proces natuurlijk CO . vrijkomt 2 door de ademhaling (of ademhaling) van microben die dode organismen afbreken, een deel van de koolstof van planten kan decennia of zelfs eeuwen onder de grond blijven. Samen, landplanten en bodems bevatten ongeveer 2, 500 gigaton koolstof - ongeveer drie keer meer dan in de atmosfeer wordt vastgehouden.

Omdat planten (vooral bomen) zulke uitstekende natuurlijke opslagplaatsen voor koolstof zijn, het is logisch dat het vergroten van de overvloed aan planten over de hele wereld atmosferische CO . zou kunnen verminderen 2 concentraties.

Planten hebben vier basisingrediënten nodig om te groeien:licht, CO 2 , water en voedingsstoffen (zoals stikstof en fosfor, dezelfde elementen die aanwezig zijn in plantenmest). Duizenden wetenschappers over de hele wereld bestuderen hoe plantengroei varieert in relatie tot deze vier ingrediënten, om te voorspellen hoe vegetatie zal reageren op klimaatverandering.

Dit is een verrassend uitdagende taak, gezien het feit dat mensen tegelijkertijd zoveel aspecten van de natuurlijke omgeving wijzigen door de aarde te verwarmen, veranderende regenpatronen, grote stukken bos in kleine fragmenten hakken en uitheemse soorten introduceren waar ze niet thuishoren. Er zijn ook meer dan 350, 000 soorten bloeiende planten op het land en elk reageert op unieke manieren op milieu-uitdagingen.

Vanwege de gecompliceerde manieren waarop mensen de planeet veranderen, er is veel wetenschappelijke discussie over de precieze hoeveelheid koolstof die planten uit de atmosfeer kunnen opnemen. Maar onderzoekers zijn het er unaniem over eens dat landecosystemen een eindige capaciteit hebben om koolstof op te nemen.

Als we ervoor zorgen dat bomen genoeg water hebben om te drinken, bossen zullen lang en weelderig worden, schaduwrijke luifels creëren die kleinere bomen van licht verhongeren. Als we de concentratie CO . verhogen 2 in de lucht, planten zullen het gretig opnemen - totdat ze niet langer genoeg mest uit de grond kunnen halen om aan hun behoeften te voldoen. Net als een bakker die een cake maakt, planten hebben CO . nodig 2 , stikstof en fosfor in het bijzonder verhoudingen, volgens een specifiek recept voor het leven.

Met het oog op deze fundamentele beperkingen, wetenschappers schatten dat de landecosystemen op aarde voldoende extra vegetatie kunnen bevatten om tussen de 40 en 100 gigaton koolstof uit de atmosfeer te absorberen. Zodra deze extra groei is gerealiseerd (een proces dat enkele decennia zal duren), er is geen capaciteit voor extra koolstofopslag op land.

Maar onze samenleving giet momenteel CO 2 met een snelheid van tien gigaton koolstof per jaar de atmosfeer in. Natuurlijke processen zullen moeite hebben om gelijke tred te houden met de stortvloed aan broeikasgassen die door de wereldeconomie worden gegenereerd. Bijvoorbeeld, Ik heb berekend dat een enkele passagier op een retourvlucht van Melbourne naar New York City ongeveer twee keer zoveel koolstof zal uitstoten (1600 kg C) als in een eik met een diameter van een halve meter (750 kg C).

Blad onder een microscoop:de stoma die zuurstof en kooldioxide reguleert is te zien. Krediet:Shutterstock/Barbol

Gevaar en belofte

Ondanks al deze algemeen erkende fysieke beperkingen op de plantengroei, er is een groeiend aantal grootschalige inspanningen om de vegetatie te vergroten om de klimaatnoodsituatie te verzachten - een zogenaamde "op de natuur gebaseerde" klimaatoplossing. Het overgrote deel van deze inspanningen is gericht op het beschermen of uitbreiden van bossen, omdat bomen vele malen meer biomassa bevatten dan struiken of grassen en daarom een groter koolstofopnamepotentieel vertegenwoordigen.

Toch kunnen fundamentele misverstanden over koolstofafvang door landecosystemen verwoestende gevolgen hebben. resulterend in verlies aan biodiversiteit en een toename van CO 2 concentraties. Dit lijkt een paradox:hoe kan het planten van bomen een negatieve invloed hebben op het milieu?

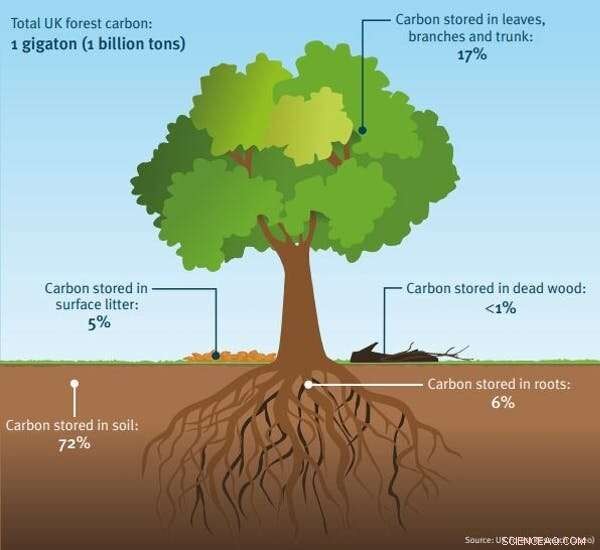

Het antwoord ligt in de subtiele complexiteit van koolstofafvang in natuurlijke ecosystemen. Om milieuschade te voorkomen, we moeten afzien van het aanleggen van bossen waar ze van nature niet thuishoren, vermijd "perverse prikkels" om bestaand bos te kappen om nieuwe bomen te planten, en overweeg hoe de zaailingen die vandaag zijn geplant, het de komende decennia zullen vergaan.

Alvorens enige uitbreiding van de boshabitat uit te voeren, we moeten ervoor zorgen dat bomen op de juiste plaats worden geplant, omdat niet alle ecosystemen op het land bomen kunnen of moeten ondersteunen. Het planten van bomen in ecosystemen die normaal gesproken worden gedomineerd door andere soorten vegetatie, leidt vaak niet tot koolstofvastlegging op de lange termijn.

Een bijzonder illustratief voorbeeld is afkomstig uit Schotse veengebieden - uitgestrekte stukken land waar de laaggelegen vegetatie (meestal mossen en grassen) groeit in constant drassige, vochtige grond. Omdat de ontbinding in de zure en drassige bodems zeer langzaam gaat, dode planten hopen zich gedurende zeer lange tijd op, turf aanleggen. Het is niet alleen de vegetatie die behouden blijft:veenmoerassen mummificeren ook zogenaamde "veenlichamen" - de bijna intacte overblijfselen van mannen en vrouwen die millennia geleden stierven. In feite, Britse veengebieden bevatten 20 keer meer koolstof dan in de bossen van het land.

Maar aan het eind van de 20e eeuw sommige Schotse moerassen werden drooggelegd voor het planten van bomen. Door de grond te drogen, konden boomzaailingen zich vestigen, maar zorgde er ook voor dat het verval van het veen versnelde. Ecoloog Nina Friggens en haar collega's van de Universiteit van Exeter schatten dat de afbraak van drogende turf meer koolstof vrijmaakte dan de groeiende bomen konden opnemen. Duidelijk, veengebieden kunnen het klimaat het beste beschermen als ze aan hun lot worden overgelaten.

Hetzelfde geldt voor graslanden en savannes, waar branden een natuurlijk onderdeel van het landschap zijn en vaak bomen verbranden die zijn geplant waar ze niet thuishoren. Dit principe geldt ook voor Arctische toendra's, waar de inheemse vegetatie de hele winter bedekt is met sneeuw, reflecterend licht en warmte terug naar de ruimte. hoog planten, donkerbladige bomen in deze gebieden kunnen de opname van warmte-energie verhogen, en leiden tot lokale opwarming.

Maar zelfs het planten van bomen in boshabitats kan leiden tot negatieve milieueffecten. Vanuit het perspectief van zowel koolstofvastlegging als biodiversiteit, alle bossen zijn niet gelijk - natuurlijk aangelegde bossen bevatten meer soorten planten en dieren dan plantagebossen. Ze bevatten vaak meer koolstof, te. Maar beleid gericht op het bevorderen van het planten van bomen kan onbedoeld de ontbossing van gevestigde natuurlijke habitats stimuleren.

Where carbon is stored in a typical temperate forest in the UK. Credit:UK Forest Research, CC BY

A recent high-profile example concerns the Mexican government's Sembrando Vida program, which provides direct payments to landowners for planting trees. Het probleem? Many rural landowners cut down well established older forest to plant seedlings. This decision, while quite sensible from an economic point of view, has resulted in the loss of tens of thousands of hectares of mature forest.

This example demonstrates the risks of a narrow focus on trees as carbon absorption machines. Many well meaning organizations seek to plant the trees which grow the fastest, as this theoretically means a higher rate of CO 2 "drawdown" from the atmosphere.

Yet from a climate perspective, what matters is not how quickly a tree can grow, but how much carbon it contains at maturity, and how long that carbon resides in the ecosystem. As a forest ages, it reaches what ecologists call a "steady state"—this is when the amount of carbon absorbed by the trees each year is perfectly balanced by the CO 2 released through the breathing of the plants themselves and the trillions of decomposer microbes underground.

This phenomenon has led to an erroneous perception that old forests are not useful for climate mitigation because they are no longer growing rapidly and sequestering additional CO 2 . The misguided "solution" to the issue is to prioritize tree planting ahead of the conservation of already established forests. This is analogous to draining a bathtub so that the tap can be turned on full blast:the flow of water from the tap is greater than it was before—but the total capacity of the bath hasn't changed. Mature forests are like bathtubs full of carbon. They are making an important contribution to the large, maar eindig, quantity of carbon that can be locked away on land, and there is little to be gained by disturbing them.

What about situations where fast growing forests are cut down every few decades and replanted, with the extracted wood used for other climate-fighting purposes? While harvested wood can be a very good carbon store if it ends up in long lived products (like houses or other buildings), surprisingly little timber is used in this way.

evenzo, burning wood as a source of biofuel may have a positive climate impact if this reduces total consumption of fossil fuels. But forests managed as biofuel plantations provide little in the way of protection for biodiversity and some research questions the benefits of biofuels for the climate in the first place.

Fertilize a whole forest

Scientific estimates of carbon capture in land ecosystems depend on how those systems respond to the mounting challenges they will face in the coming decades. All forests on Earth—even the most pristine—are vulnerable to warming, changes in rainfall, increasingly severe wildfires and pollutants that drift through the Earth's atmospheric currents.

Some of these pollutants, echter, contain lots of nitrogen (plant fertilizer) which could potentially give the global forest a growth boost. By producing massive quantities of agricultural chemicals and burning fossil fuels, humans have massively increased the amount of "reactive" nitrogen available for plant use. Some of this nitrogen is dissolved in rainwater and reaches the forest floor, where it can stimulate tree growth in some areas.

Implications of large-scale tree planting in various climatic zones and ecosystems. Credit:Stacey McCormack/Köppen climate classification, Auteur verstrekt

As a young researcher fresh out of graduate school, I wondered whether a type of under-studied ecosystem, known as seasonally dry tropical forest, might be particularly responsive to this effect. There was only one way to find out:I would need to fertilize a whole forest.

Working with my postdoctoral adviser, the ecologist Jennifer Powers, and expert botanist Daniel Pérez Avilez, I outlined an area of the forest about as big as two football fields and divided it into 16 plots, which were randomly assigned to different fertilizer treatments. For the next three years (2015-2017) the plots became among the most intensively studied forest fragments on Earth. We measured the growth of each individual tree trunk with specialised, hand-built instruments called dendrometers.

We used baskets to catch the dead leaves that fell from the trees and installed mesh bags in the ground to track the growth of roots, which were painstakingly washed free of soil and weighed. The most challenging aspect of the experiment was the application of the fertilizers themselves, which took place three times a year. Wearing raincoats and goggles to protect our skin against the caustic chemicals, we hauled back-mounted sprayers into the dense forest, ensuring the chemicals were evenly applied to the forest floor while we sweated under our rubber coats.

Helaas, our gear didn't provide any protection against angry wasps, whose nests were often concealed in overhanging branches. Maar, our efforts were worth it. Na drie jaar, we could calculate all the leaves, wood and roots produced in each plot and assess carbon captured over the study period. We found that most trees in the forest didn't benefit from the fertilizers—instead, growth was strongly tied to the amount of rainfall in a given year.

This suggests that nitrogen pollution won't boost tree growth in these forests as long as droughts continue to intensify. To make the same prediction for other forest types (wetter or drier, younger or older, warmer or cooler) such studies will need to be repeated, adding to the library of knowledge developed through similar experiments over the decades. Yet researchers are in a race against time. Experiments like this are slow, painstaking, sometimes backbreaking work and humans are changing the face of the planet faster than the scientific community can respond.

Humans need healthy forests

Supporting natural ecosystems is an important tool in the arsenal of strategies we will need to combat climate change. But land ecosystems will never be able to absorb the quantity of carbon released by fossil fuel burning. Rather than be lulled into false complacency by tree planting schemes, we need to cut off emissions at their source and search for additional strategies to remove the carbon that has already accumulated in the atmosphere.

Does this mean that current campaigns to protect and expand forest are a poor idea? Emphatically not. The protection and expansion of natural habitat, particularly forests, is absolutely vital to ensure the health of our planet. Forests in temperate and tropical zones contain eight out of every ten species on land, yet they are under increasing threat. Nearly half of our planet's habitable land is devoted to agriculture, and forest clearing for cropland or pasture is continuing apace.

In de tussentijd, the atmospheric mayhem caused by climate change is intensifying wildfires, worsening droughts and systematically heating the planet, posing an escalating threat to forests and the wildlife they support. What does that mean for our species? Again and again, researchers have demonstrated strong links between biodiversity and so-called "ecosystem services"—the multitude of benefits the natural world provides to humanity.

Dendrometer devices wrapped around tree trunks to measure growth. Auteur verstrekt

Carbon capture is just one ecosystem service in an incalculably long list. Biodiverse ecosystems provide a dizzying array of pharmaceutically active compounds that inspire the creation of new drugs. They provide food security in ways both direct (think of the millions of people whose main source of protein is wild fish) and indirect (for example, a large fraction of crops are pollinated by wild animals).

Natural ecosystems and the millions of species that inhabit them still inspire technological developments that revolutionize human society. Bijvoorbeeld, take the polymerase chain reaction ("PCR") that allows crime labs to catch criminals and your local pharmacy to provide a COVID test. PCR is only possible because of a special protein synthesized by a humble bacteria that lives in hot springs.

As an ecologist, I worry that a simplistic perspective on the role of forests in climate mitigation will inadvertently lead to their decline. Many tree planting efforts focus on the number of saplings planted or their initial rate of growth—both of which are poor indicators of the forest's ultimate carbon storage capacity and even poorer metric of biodiversity. Belangrijker, viewing natural ecosystems as "climate solutions" gives the misleading impression that forests can function like an infinitely absorbent mop to clean up the ever increasing flood of human caused CO 2 uitstoot.

Gelukkig, many big organizations dedicated to forest expansion are incorporating ecosystem health and biodiversity into their metrics of success. Iets meer dan een jaar geleden, I visited an enormous reforestation experiment on the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico, operated by Plant-for-the-Planet—one of the world's largest tree planting organizations. After realizing the challenges inherent in large scale ecosystem restoration, Plant-for-the-Planet has initiated a series of experiments to understand how different interventions early in a forest's development might improve tree survival.

But that is not all. Led by Director of Science Leland Werden, researchers at the site will study how these same practices can jump-start the recovery of native biodiversity by providing the ideal environment for seeds to germinate and grow as the forest develops. These experiments will also help land managers decide when and where planting trees benefits the ecosystem and where forest regeneration can occur naturally.

Viewing forests as reservoirs for biodiversity, rather than simply storehouses of carbon, complicates decision making and may require shifts in policy. I am all too aware of these challenges. I have spent my entire adult life studying and thinking about the carbon cycle and I too sometimes can't see the forest for the trees. One morning several years ago, I was sitting on the rainforest floor in Costa Rica measuring CO 2 emissions from the soil—a relatively time intensive and solitary process.

As I waited for the measurement to finish, I spotted a strawberry poison dart frog—a tiny, jewel-bright animal the size of my thumb—hopping up the trunk of a nearby tree. Gefascineerd, I watched her progress towards a small pool of water held in the leaves of a spiky plant, in which a few tadpoles idly swam. Once the frog reached this miniature aquarium, the tiny tadpoles (her children, as it turned out) vibrated excitedly, while their mother deposited unfertilised eggs for them to eat. As I later learned, frogs of this species (Oophaga pumilio) take very diligent care of their offspring and the mother's long journey would be repeated every day until the tadpoles developed into frogs.

It occurred to me, as I packed up my equipment to return to the lab, that thousands of such small dramas were playing out around me in parallel. Forests are so much more than just carbon stores. They are the unknowably complex green webs that bind together the fates of millions of known species, with millions more still waiting to be discovered. To survive and thrive in a future of dramatic global change, we will have to respect that tangled web and our place in it.

Dit artikel is opnieuw gepubliceerd vanuit The Conversation onder een Creative Commons-licentie. Lees het originele artikel.

Rood, groente, en blauw licht kan worden gebruikt om genexpressie in gemanipuleerde E. coli te regelen

Rood, groente, en blauw licht kan worden gebruikt om genexpressie in gemanipuleerde E. coli te regelen Hoe potentieel schadelijke vrije radicalen in sigarettenrook te meten?

Hoe potentieel schadelijke vrije radicalen in sigarettenrook te meten? Wetenschappers ontwikkelen lithium-ionbatterij die niet vlam vat

Wetenschappers ontwikkelen lithium-ionbatterij die niet vlam vat Hoe heterogene en homogene mengsels te identificeren

Hoe heterogene en homogene mengsels te identificeren Water beïnvloedt de plakkerigheid van hyaluronan

Water beïnvloedt de plakkerigheid van hyaluronan

NRL werkt weersvoorspellingsmodel voor tropische cyclonen bij

NRL werkt weersvoorspellingsmodel voor tropische cyclonen bij Studie van Redoubt en andere vulkanen verbetert de detectie van onrust

Studie van Redoubt en andere vulkanen verbetert de detectie van onrust Met vindingrijkheid en solidariteit, Cubanen bereiden zich voor op Irma

Met vindingrijkheid en solidariteit, Cubanen bereiden zich voor op Irma COVID-19 lockdown benadrukt ozonchemie in China

COVID-19 lockdown benadrukt ozonchemie in China Onderzoek toont verband aan tussen woonstijlen en hoog waterverbruik

Onderzoek toont verband aan tussen woonstijlen en hoog waterverbruik

Hoofdlijnen

- De definitie van abiotische en biotische factoren

- De functie van veel eiwitten blijft onduidelijk

- Een niet-verslavende opioïde pijnstiller zonder bijwerkingen

- Meeluisteren:akoestische bewakingsapparatuur detecteert illegale jacht en houtkap

- De kenmerken van de mitochondria

- Regenboogpauwspinnen kunnen nieuwe optische technologieën inspireren

- Het grote structurele voordeel Eukaryoten hebben over prokaryoten

- Marihuanaboerderijen stellen gevlekte uilen bloot aan rattengif in Noordwest-Californië

- Wat zijn de functies van koolhydraten in planten en dieren?

- Hittegolf zorgt voor enorm koolstofverlies op werelderfgoed

- De dichtstbevolkte staat van India verbiedt plastic, nogmaals

- Hoe beïnvloedt klimaatverandering de biodiversiteit?

- Europees parlement, EU-lidstaten bereiken doel om CO2 te verminderen

- De ramp met de zee in Sri Lanka verergert naarmate de milieutol stijgt

Wetenschappers oogsten gegevens van de rommelende Kilauea-vulkaan in Hawaï

Wetenschappers oogsten gegevens van de rommelende Kilauea-vulkaan in Hawaï Hoe het negatieve over een elektrisch snoer te vertellen

Hoe het negatieve over een elektrisch snoer te vertellen  Waterkwaliteit:een kwestie van perspectief

Waterkwaliteit:een kwestie van perspectief Venus:Zou het echt leven kunnen herbergen? Nieuwe studie zorgt voor een verrassing

Venus:Zou het echt leven kunnen herbergen? Nieuwe studie zorgt voor een verrassing Dubbelsterren met onverklaarbaar dimpatroon

Dubbelsterren met onverklaarbaar dimpatroon Kernenergieprogramma's vergroten de kans op proliferatie niet, studie vondsten

Kernenergieprogramma's vergroten de kans op proliferatie niet, studie vondsten Zeefdruk, nPERT-zonnecellen met groot oppervlak overtreffen de efficiëntie van 23 procent

Zeefdruk, nPERT-zonnecellen met groot oppervlak overtreffen de efficiëntie van 23 procent Hoe ademt een octopus?

Hoe ademt een octopus?

- Elektronica

- Biologie

- Zonsverduistering

- Wiskunde

- French | Italian | Spanish | Portuguese | Swedish | German | Dutch | Danish | Norway |

-

Wetenschap © https://nl.scienceaq.com