Wetenschap

Hoe zou een duurzame ruimteomgeving eruit zien?

Krediet:Pixabay/CC0 publiek domein

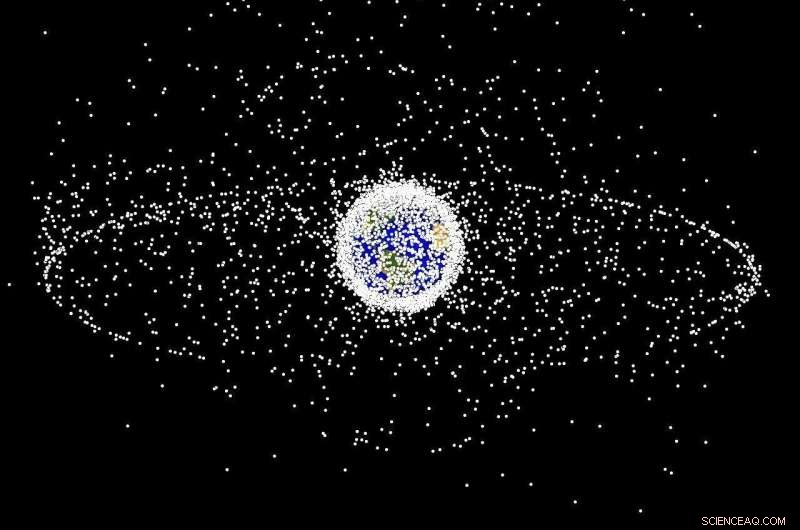

4 oktober 2022 zal een gunstige dag zijn, aangezien de mensheid de 65e verjaardag van het begin van het ruimtetijdperk viert. Het begon allemaal in 1957 met de lancering van de Sovjet-satelliet Spoetnik-1, de eerste kunstmatige satelliet die ooit in een baan om de aarde werd gebracht. Sindsdien zijn er ongeveer 8.900 satellieten gelanceerd vanuit meer dan 40 landen wereldwijd. Dit heeft geleid tot toenemende bezorgdheid over ruimtepuin en het gevaar dat het vertegenwoordigt voor toekomstige sterrenbeelden, ruimtevaartuigen en zelfs habitats in een lage baan om de aarde (LEO).

Dit heeft geleid tot veel voorgestelde oplossingen voor het opruimen van "ruimteafval", evenals tot satellietontwerpen waarmee ze uit hun baan zouden kunnen verdwijnen en verbranden. Helaas zijn er nog steeds vragen of een planeet omringd door megasterrenbeelden op de lange termijn houdbaar is. Een recent onderzoek door James A. Blake, een onderzoeker aan de Universiteit van Warwick, onderzocht de evolutie van de puinomgeving in LEO en beoordeelde of toekomstige ruimteoperaties duurzaam kunnen worden uitgevoerd.

Voor zijn Ph.D. project richtte Blake zich op de beeldvorming en het volgen van ruimteschroot in geosynchrone banen om de aarde (GEO's) ongeveer 36.000 km (22.370 mijl) boven de evenaar. In dit gebied van de ruimte volgen satellieten de rotatie van de aarde en hebben ze dezelfde omlooptijd als de aarde, waardoor ze zeer gewild zijn voor telecommunicatie. De ruimte in deze regio is echter zeer beperkt, wat kan leiden tot ernstige problemen van overbevolking en puin.

Blake's belangrijkste werk was met name een onderzoek van vaag geostationair puin, uitgevoerd met behulp van de Isaac Newton-telescoop op het Roque de los Muchachos-observatorium op het eiland La Palma. Zijn werk werd samengevat in een studie met de titel "DebrisWatch I:A survey of vaag geosynchronous puin", die in januari 2021 verscheen in het tijdschrift Advances in Space Research. Zoals hij in dit onderzoek aangaf, is de populatie van puin in GEO niet goed beperkt, maar vormt het een groeiend probleem.

Een historisch probleem

Volgens het Space Debris Office (SDO) van de ESA zijn er op 3 maart 2022 ongeveer 12.720 satellieten in een baan om de aarde gelanceerd sinds Spoetnik-1. Hiervan blijven er naar schatting 7.810 in een baan om de aarde, waarvan er ongeveer 5.200 nog operationeel zijn. Alles bij elkaar worden ongeveer 29.860 puinobjecten in LEO regelmatig gevolgd door aardobservatienetwerken en worden ze bijgehouden in hun catalogus.

Eerder werd gedacht dat de populatie van puin in GEO vrij verwaarloosbaar zou zijn vanwege de strikte afstandsregels die bedoeld zijn om ervoor te zorgen dat satellieten niet botsen. De recente schijnbare vernietiging van communicatiesatellieten - AMC-9, eigendom van het in Luxemburg gevestigde telecombedrijf SES S.A., en Lockheed Martin's Telkom-1 - heeft echter duidelijk aangetoond dat er een puinveld bestaat in GEO. This presents new implications for future constellations in GEO.

As Blake told Universe Today via email, charting the evolution of space debris is essential to the future of debris mitigation:

"Sputnik 1 was the first of thousands of satellites to be launched into Earth orbit over the past six decades, and that number continues to grow rapidly. Some have re-entered the Earth's atmosphere, while others are orbiting in an abandoned and uncontrolled state, posing a threat to the active satellites we rely on.

"Over time, the orbital debris population has grown due to accidental explosions and collisions, alongside intentional anti-satellite tests. The vast majority of debris produced by these events remains invisible to us, too small to be detected by our current generation of surveillance networks, yet still holding the potential to severely damage spacecraft."

According to Blake, there's a lesson to be learned from humanity's exploitation of the near-Earth environment. In keeping with the interconnected nature of space exploration and life on Earth, this same lesson applies equally to humanity's activities on the ground. In short, humanity needs to act sustainably so that future generations can enjoy and benefit from the freedoms we've enjoyed since the dawn of the Space Age. To do this, says Blake, collision avoidance is a must:

"Effective collision avoidance requires timely and accurate information. As satellite and debris catalogs grow ever larger, surveillance networks are being tasked with monitoring more and more objects to provide sufficient warning to operators, who can then opt to maneuver their craft out of harm's way."

Monitoring and mitigating

The current strategy for preventing an uncontrollable debris environment in orbit involves a two-pronged approach:tracking and "passivating." The task of tracking satellites and debris is handled by several space agencies and government offices worldwide. For instance, the Joint Space Operation Center at Vanderburg Air Force Base in California (JSpOC) uses the Space Surveillance Networks (SSNs), a combination of optical and radar sensors, to monitor satellites and debris in orbit.

The NASA Orbital Debris Program Office (ODPO), located at the Johnson Space Center, measures the orbital debris environment while developing measures to control debris growth. The Office of Safety and Mission Assurance (OSMA), located at NASA HQ in Washington D.C., is responsible for developing, implementing, and overseeing agency-wide policies and procedures to ensure safety, reliability, and space environment sustainability.

There's also the ESA's Space Debris Office (SDO)—located at the European Space Operations Center (ESOC) in Darmstadt, Germany—which is responsible for measuring and modeling the orbital debris environment and developing protection and mitigation strategies. It also coordinates activities and research efforts with the ESA's constituent agencies, which form the European Network of Competences on Space Debris (SD NoC).

At the international level, there's the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee (IADC), a forum that includes thirteen national space agencies (including NASA, Roscosmos, the ESA, and the Indian and Chinese space agencies). This body developed guidelines in 2001 that have been revised multiple times (the most recent occurring in 2020) and have since been adopted by the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (UNCOPUOS).

On the other end of things, there's the famous "25-year rule," where operators are encouraged to dispose of satellites within 25 years of mission completion via atmospheric re-entry. Low-altitude satellites may already be naturally capable of doing this. In contrast, potentially non-compliant satellites can be outfitted with thrusters, drag sails, and other instruments to accelerate the deorbiting process. As Blake explained:

"Operators are encouraged to 'passivate' spacecraft at the end of their mission, by depleting or saving any remnant sources of internal energy onboard the satellite or rocket body, thus reducing the chances of explosion. Adherence to the '25-year rule' for deorbiting spacecraft in low Earth orbit is still concerningly low, and a boost to cooperation on an international scale will be paramount to tackling the debris problem."

A problem of policy

In the end, Blake indicates that one of the greatest hurdles to achieving sustainability in space is policy. For the past few decades, the IADC guidelines adopted by UNCOUPOUS have formed the basis for standard mitigation practices on the international stage. Unfortunately, these guidelines are voluntary (i.e., not legally binding), and some space-faring nations have chosen not to include them in their national regulatory frameworks.

In addition, adherence to the "25-years rule" remains very low in LEO, and the process of re-entry is not a viable option for objects in the high-altitude GSO region. As a result, operators will typically attempt to raise decommissioned satellites into so-called "graveyard" orbits well beyond GSO—or what is known as a supersynchronous orbit (SSO). This has the effect of clearing the operational zone in orbit for use by future satellites, but the debris can still pose a threat to spacecraft destined for the Moon or deep-space.

What is needed, says Blake, is a policy of active debris removal (ADR) that works in tandem with stricter adherence to regulations for debris mitigation:

"Ultimately, we'll want to conduct regular removal missions to actively dispose of dead spacecraft and debris, though a number of technological hurdles are yet to be cleared. As evidenced by the recent Russian ASAT test back in November 2021, there is also a need for internationally recognized, legally binding regulations, to sanction against reckless behavior."

In addition, NASA, the ESA, the China National Space Agency (CNSA), and other space agencies are currently testing ADR systems. Concepts include Earth-based directed-energy arrays (lasers), spacecraft equipped with plasma beams, harpoons and nets, and magnetic space tugs. In recent years, says Blake, there have also been efforts to formulate a "space sustainability rating" that would incentivize operators to adhere to safe practices and debris mitigation. However, several questions remain unanswered.

For instance, with access to space becoming more widespread, how does a regulatory framework compare University-led CubeSat experiments to commercial constellations of satellites (a la Starlink)? Also, how will lawmakers attribute liability in the event of a collision involving uncontrolled debris? And what mechanisms will be in place to ensure a level playing field between emerging space agencies and those with a decades-long presence in space?

The debate around these questions and attempts to find solutions are actively unfolding around us right now. It has also led to the rise of non-profit organizations like the Space Court Foundation (SCF) the Space Generation Advisory Council (SGAC). There are also the time-honored efforts to formulate and crystallize policy by the Institute of Air &Space Law (IASL) at McGill University and the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA).

As our presence in space continues to grow, we can expect some spirited debate, resolutions, and impressive innovations in the coming years. As always, the driving force behind these developments will be a basic matter of necessity. Humanity's future in space depends upon accessibility and safety, something that cannot happen with huge debris fields in orbit.

Slimme simulaties brengen het gedrag van verrassende constructies in kaart

Slimme simulaties brengen het gedrag van verrassende constructies in kaart De elektrische handtekening van fosfaten helpt bij het detecteren van belangrijke mobiele gebeurtenissen

De elektrische handtekening van fosfaten helpt bij het detecteren van belangrijke mobiele gebeurtenissen Hoe Tantalium wordt gedolven

Hoe Tantalium wordt gedolven Controle over de productie van stabiele aerogels

Controle over de productie van stabiele aerogels Weg van plastic:het geval van solid body wash

Weg van plastic:het geval van solid body wash

Hoofdlijnen

- Consortium kondigt vijf nieuwe embryo's van noordelijke witte neushoorn aan

- Hoe groeifactor Midkine AMPK onderdrukt tijdens kankerprogressie

- Nieuwe methodologie voorspelt coronavirus en andere infectieziektebedreigingen voor dieren in het wild

- Hoe zeer resistente schimmelstammen ontstaan

- The Differences Between Kinetochore & Nonkinetochore

- Chloroplast: definitie, structuur en functie (met diagram)

- Organische materie speelt een sleutelrol bij stikstofverlies door modderige/zandige sedimenten op de kust van de Oost-Chinese Zee

- Moeten we de genen van buitengewone mensen sparen voor klonen?

- Symbiotische bacteriën beschermen keverlarven tegen ziekteverwekkers

- Ruimtevaartorganisatie:menselijke urine kan helpen bij het maken van beton op de maan

- Sterrenstelsels worden groter en gezwollen naarmate ze ouder worden:studie

- Nieuwe Ceres-weergaven terwijl Dawn hoger komt

- De ongelooflijke uitdaging om zware ladingen op Mars te landen

- Stamcellen lijken sneller in de ruimte

Veteraan NASA-ruimtevrouw krijgt drie extra maanden in een baan om de aarde (update)

Veteraan NASA-ruimtevrouw krijgt drie extra maanden in een baan om de aarde (update) Zorgt smog voor prachtige zonsondergangen?

Zorgt smog voor prachtige zonsondergangen?  Kosteneffectieve marketingcampagnes op sociale media

Kosteneffectieve marketingcampagnes op sociale media Samsung plant 22 miljard dollar voor kunstmatige intelligentie auto's

Samsung plant 22 miljard dollar voor kunstmatige intelligentie auto's Waterworld - kunnen we leren leven met overstromingen?

Waterworld - kunnen we leren leven met overstromingen? De evolutie van voedingsstrategieën bij oude krokodillen ontrafelen

De evolutie van voedingsstrategieën bij oude krokodillen ontrafelen Perfecte optiek door lichtverstrooiing

Perfecte optiek door lichtverstrooiing Wat is een oplossing in de wetenschap?

Wat is een oplossing in de wetenschap?

- Elektronica

- Biologie

- Zonsverduistering

- Wiskunde

- French | Italian | Spanish | Portuguese | Swedish | German | Dutch | Danish | Norway |

-

Wetenschap © https://nl.scienceaq.com