Wetenschap

Hoe lang tot middernacht? De Doomsday Clock meet meer dan nucleair risico, en staat op het punt opnieuw te worden gereset

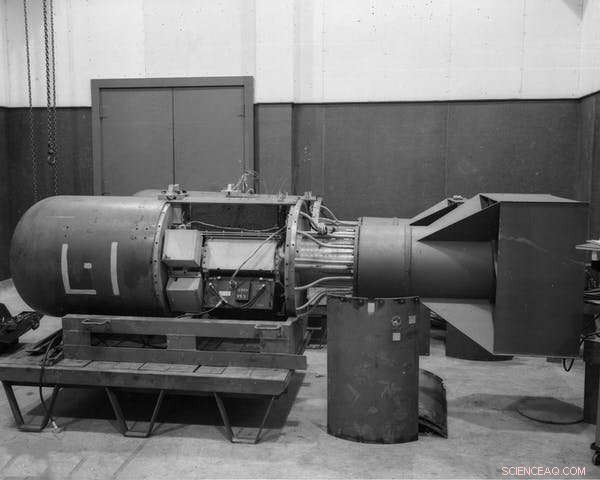

De atoombom met de codenaam 'Little Boy', hetzelfde type dat later op Hiroshima werd gedropt, in het Los Alamos National Laboratory in 1944. Credit:Shutterstock

In minder dan 24 uur zal het Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists de Doomsday Clock updaten. Het is momenteel 100 seconden na middernacht - de metaforische tijd waarin de mensheid de wereld zou kunnen vernietigen met eigen technologieën.

De wijzers zijn nog nooit zo dicht bij middernacht geweest. Er is weinig hoop dat het terugkomt op wat zijn 75e verjaardag zal zijn.

Doe mee met de 75e verjaardag van de Doomsday Clock-aankondiging op donderdag 20 januari om 10:00 uur EST

Details:https://t.co/UgE8wtUvND pic.twitter.com/RyWu91AnfP

— Bulletin van de atoomwetenschappers (@BulletinAtomic) 9 januari 2022

De klok is oorspronkelijk bedacht als een manier om de aandacht te vestigen op nucleaire vuurzee. Maar de wetenschappers die het Bulletin in 1945 oprichtten, waren minder gefocust op het eerste gebruik van 'de bom' dan op de irrationaliteit van het aanleggen van voorraden wapens omwille van de nucleaire hegemonie.

Ze realiseerden zich dat meer bommen de kansen op het winnen van een oorlog niet vergrootten of iemand in veiligheid brachten wanneer slechts één bom voldoende zou zijn om New York te vernietigen.

Hoewel nucleaire vernietiging de meest waarschijnlijke en acute existentiële bedreiging voor de mensheid blijft, is het nu slechts een van de potentiële rampen die de Doomsday Clock meet. Zoals het Bulletin het stelt:"De klok is een universeel erkende indicator geworden van de kwetsbaarheid van de wereld voor rampen door kernwapens, klimaatverandering en ontwrichtende technologieën in andere domeinen."

Meerdere verbonden bedreigingen

Op persoonlijk vlak voel ik enige academische verwantschap met de klokkenmakers. Mijn mentoren, met name Aaron Novick, en anderen die een diepgaande invloed hebben gehad op hoe ik mijn eigen wetenschappelijke discipline en benadering van de wetenschap zie, behoorden tot degenen die het vroege Bulletin hebben gevormd en er lid van zijn geworden.

In 2022 gaat hun waarschuwing verder dan massavernietigingswapens en omvat ze ook andere technologieën die potentieel existentiële gevaren concentreren, waaronder klimaatverandering en de grondoorzaken daarvan in overconsumptie en extreme welvaart.

Veel van deze bedreigingen zijn al bekend. Commercieel chemisch gebruik is bijvoorbeeld alomtegenwoordig, net als het giftige afval dat het creëert. Alleen al in de VS zijn er tienduizenden grootschalige afvallocaties, met 1.700 gevaarlijke "superfundlocaties" die prioriteit krijgen bij het opruimen.

Zoals orkaan Harvey liet zien toen hij in 2017 het gebied van Houston trof, zijn deze locaties extreem kwetsbaar. An estimated two million kilograms of airborne contaminants above regulatory limits were released, 14 toxic waste sites were flooded or damaged, and dioxins were found in a major river at levels over 200 times higher than recommended maximum concentrations.

That was just one major metropolitan area. With increasing storm severity due to climate change, the risks to toxic waste sites grow.

At the same time, the Bulletin has increasingly turned its attention to the rise of artificial intelligence, autonomous weaponry, and mechanical and biological robotics.

The movie clichés of cyborgs and "killer robots" tend to disguise the true risks. For example, gene drives are an early example of biological robotics already in development. Genome editing tools are used to create gene drive systems that spread through normal pathways of reproduction but are designed to destroy other genes or offspring of a particular sex.

Climate change and affluence

As well as being an existential threat in its own right, climate change is connected to the risks posed by these other technologies.

Both genetically engineered viruses and gene drives, for example, are being developed to stop the spread of infectious diseases carried by mosquitoes, whose habitats spread on a warming planet.

Once released, however, such biological "robots" may evolve capabilities beyond our ability to control them. Even a few misadventures that reduce biodiversity could provoke social collapse and conflict.

Similarly, it's possible to imagine the effects of climate change causing concentrated chemical waste to escape confinement. Meanwhile, highly dispersed toxic chemicals can be concentrated by storms, picked up by floodwaters and distributed into rivers and estuaries.

The result could be the despoiling of agricultural land and fresh water sources, displacing populations and creating "chemical refugees."

Resetting the clock

Given that the Doomsday Clock has been ticking for 75 years, with myriad other environmental warnings from scientists in that time, what of humanity's ability to imagine and strive for a different future?

Part of the problem lies in the role of science itself. While it helps us understand the risks of technological progress, it also drives that process in the first place. And scientists are people, too—part of the same cultural and political processes that influence everyone.

J. Robert Oppenheimer—the "father of the atomic bomb"—described this vulnerability of scientists to manipulation, and to their own naivete, ambition and greed, in 1947:"In some sort of crude sense which no vulgarity, no humor, no overstatement can quite extinguish, the physicists have known sin; and this is a knowledge which they cannot lose."

If the bomb was how physicists came to know sin, then perhaps those other existential threats that are the product of our addiction to technology and consumption are how others come to know it, too.

Ultimately, the interrelated nature of these threats is what the Doomsday Clock exists to remind us of.

Springende hagedissen:onderzoek test de grenzen van gekko-adhesie

Springende hagedissen:onderzoek test de grenzen van gekko-adhesie Identificatie van een ongrijpbaar molecuul dat de sleutel is tot verbrandingschemie

Identificatie van een ongrijpbaar molecuul dat de sleutel is tot verbrandingschemie Bananenschillen maken suikerkoekjes beter voor je

Bananenschillen maken suikerkoekjes beter voor je Wat moet je weten om molariteit te berekenen?

Wat moet je weten om molariteit te berekenen?  Duidelijkste zicht ooit op celmembraan levert onverwachte structuur op, onderzoeksmogelijkheden

Duidelijkste zicht ooit op celmembraan levert onverwachte structuur op, onderzoeksmogelijkheden

Hoe koralen die Bikini-atol opnieuw koloniseerden na atoombomtests zich aanpasten aan aanhoudende straling?

Hoe koralen die Bikini-atol opnieuw koloniseerden na atoombomtests zich aanpasten aan aanhoudende straling? Verontreinigende stoffen uit schoorstenen verwijderen

Verontreinigende stoffen uit schoorstenen verwijderen  Hittegolven bedreigen stadsbewoners, vooral minderheden en de armen

Hittegolven bedreigen stadsbewoners, vooral minderheden en de armen Hoe lang kan een dolfijn zijn adem inhouden?

Hoe lang kan een dolfijn zijn adem inhouden?  Californië tot zweepslag tussen droogte, overstromingen:studie

Californië tot zweepslag tussen droogte, overstromingen:studie

Hoofdlijnen

- Wat zijn de primaire functies van fosfolipiden?

- Wat zijn enkele materialen die ik zou kunnen gebruiken om plantencellen te maken?

- Steenkoralen gebruiken een verfijnd ingebouwd ventilatiesysteem om zichzelf te beschermen tegen omgevingsstressoren

- Microbeads zorgen ervoor dat ultrasone golven cellen veiliger kunnen stimuleren

- Angiospermen: definitie, levenscyclus, soorten en voorbeelden

- Niet zo koude eend? Man blijft zoeken naar uitgestorven vogel

- Stijgende CO2 zorgt ook voor overlast in zoetwater, studie suggereert:

- Belangrijke soorten bacteriën

- Waarom worden we ziek?

- Breed draagvlak voor ambitieus klimaatbeleid als aan vier voorwaarden wordt voldaan

- Siciliaans dorp ruimt as op, stenen van de uitbarsting van de Etna

- Ingenieurs onderzoeken stedelijke koelstrategieën met behulp van reflecterende oppervlakken

- Volgende 10 jaar cruciaal voor het behalen van klimaatdoelstellingen

- Afbeelding:Waarschuwing, Canada

Risicoprofilering van nanomaterialen stelt veiligheid voorop

Risicoprofilering van nanomaterialen stelt veiligheid voorop Hoe windbelasting op een groot vlak oppervlak te berekenen

Hoe windbelasting op een groot vlak oppervlak te berekenen Sensor kan bedrading in een gebouw of schip bewaken, en signaleren wanneer reparaties nodig zijn

Sensor kan bedrading in een gebouw of schip bewaken, en signaleren wanneer reparaties nodig zijn Nieuwe computeraanval bootst toetsaanslagkenmerken van gebruikers na en ontwijkt detectie

Nieuwe computeraanval bootst toetsaanslagkenmerken van gebruikers na en ontwijkt detectie De grootste dataset voor het zoutgehalte van het zeeoppervlak tot nu toe helpt onderzoekers om zoute wateren in kaart te brengen

De grootste dataset voor het zoutgehalte van het zeeoppervlak tot nu toe helpt onderzoekers om zoute wateren in kaart te brengen Staking Duitse luchthavens schrapt 600 vluchten

Staking Duitse luchthavens schrapt 600 vluchten 2017 was een heet en rampzalig jaar voor de Verenigde Staten, NOAA zegt

2017 was een heet en rampzalig jaar voor de Verenigde Staten, NOAA zegt Hoe gasdruk te converteren naar BTU

Hoe gasdruk te converteren naar BTU

- Elektronica

- Biologie

- Zonsverduistering

- Wiskunde

- French | Italian | Spanish | Portuguese | Swedish | German | Dutch | Danish | Norway |

-

Wetenschap © https://nl.scienceaq.com