Wetenschap

De hittegolven van tegenwoordig voelen veel heter aan dan de hitte-index aangeeft

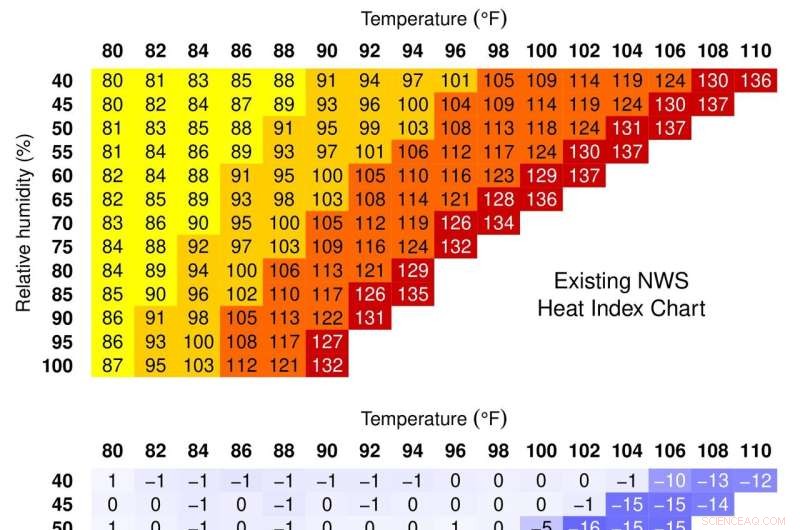

De al lang gebruikte Heat Index-tabel (boven) onderschat de schijnbare temperatuur voor de meest extreme hitte- en vochtigheidsomstandigheden die tegenwoordig voorkomen (midden). De gecorrigeerde versie (onder) is nauwkeurig over het hele bereik van temperaturen en vochtigheid die mensen zullen tegenkomen bij klimaatverandering. Krediet:David Romps en Yi-Chuan Lu, UC Berkeley

Als je tijdens de plakkerige hittegolven van deze zomer naar de hitte-index hebt gekeken en dacht:"Het voelt zeker heter aan", heb je misschien gelijk.

Uit een analyse door klimaatwetenschappers van de University of California, Berkeley, blijkt dat de schijnbare temperatuur, of hitte-index, berekend door meteorologen en de National Weather Service (NWS) om aan te geven hoe warm het aanvoelt - rekening houdend met de vochtigheid - de waargenomen temperatuur voor de meest zinderende dagen die we nu ervaren, soms met meer dan 20 graden Fahrenheit.

De bevinding heeft implicaties voor degenen die last hebben van deze hittegolven, aangezien de hitte-index een maat is voor hoe het lichaam omgaat met hitte wanneer de luchtvochtigheid hoog is, en zweten wordt minder effectief om ons af te koelen. Zweten en blozen - waarbij bloed wordt omgeleid naar haarvaten dicht bij de huid om de warmte af te voeren - en het afstoten van kleding zijn de belangrijkste manieren waarop mensen zich aanpassen aan hoge temperaturen.

Een hogere hitte-index betekent dat het menselijk lichaam tijdens deze hittegolven meer gestrest is dan volksgezondheidsfunctionarissen misschien beseffen, zeggen de onderzoekers. De NWS beschouwt momenteel een hitte-index boven 103 als gevaarlijk en boven 125 als extreem gevaarlijk.

"Meestal is de hitte-index die de National Weather Service u geeft precies de juiste waarde. Alleen in deze extreme gevallen krijgen ze het verkeerde aantal", zegt David Romps, hoogleraar aarde en planeten aan de UC Berkeley. wetenschap. "Waar het om gaat, is wanneer je de hitte-index weer in kaart brengt op fysiologische toestanden en je realiseert je, oh, deze mensen worden gestrest tot een toestand van een zeer verhoogde doorbloeding van de huid, waarbij het lichaam bijna geen trucjes meer heeft om te compenseren voor dit soort hitte en vochtigheid. Dus we zijn dichter bij die rand dan we eerst dachten."

Romps en afgestudeerde student Yi-Chuan Lu hebben hun analyse gedetailleerd beschreven in een paper dat is geaccepteerd door het tijdschrift Environmental Research Letters en online geplaatst op 12 augustus.

De hitte-index werd in 1979 bedacht door een textielfysicus, Robert Steadman, die eenvoudige vergelijkingen maakte om te berekenen wat hij de relatieve "zwoelheid" noemde van warme en vochtige, evenals hete en droge omstandigheden tijdens de zomer. Hij zag het als een aanvulling op de gevoelstemperatuurfactor die in de winter vaak wordt gebruikt om in te schatten hoe koud het aanvoelt.

Zijn model hield rekening met hoe mensen hun interne temperatuur regelen om thermisch comfort te bereiken onder verschillende externe omstandigheden van temperatuur en vochtigheid - door bewust de dikte van kleding te veranderen of onbewust de ademhaling, transpiratie en bloedstroom van de kern van het lichaam naar de huid aan te passen.

In his model, the apparent temperature under ideal conditions—an average-sized person in the shade with unlimited water—is how hot someone would feel if the relative humidity were at a comfortable level, which Steadman took to be a vapor pressure of 1,600 pascals.

For example, at 70% relative humidity and 68 F—which is often taken as average humidity and temperature—a person would feel like it's 68 F. But at the same humidity and 86 F, it would feel like 94 F.

The heat index has since been adopted widely in the United States, including by the NWS, as a useful indicator of people's comfort. But Steadman left the index undefined for many conditions that are now becoming increasingly common. For example, for a relative humidity of 80%, the heat index is not defined for temperatures above 88 F or below 59 F. Today, temperatures routinely rise above 90 F for weeks at a time in some areas, including the Midwest and Southeast.

To account for these gaps in Steadman's chart, meteorologists extrapolated into these areas to get numbers, Romps said, that are correct most of the time, but not based on any understanding of human physiology.

"There's no scientific basis for these numbers," Romps said.

He and Lu set out to extend Steadman's work so that the heat index is accurate at all temperatures and all humidities between zero and 100%.

"The original table had a very short range of temperature and humidity and then a blank region where Steadman said the human model failed," Lu said. "Steadman had the right physics. Our aim was to extend it to all temperatures so that we have a more accurate formula."

One condition under which Steadman's model breaks down is when people perspire so much that sweat pools on the skin. At that point, his model incorrectly had the relative humidity at the skin surface exceeding 100%, which is physically impossible.

"It was at that point where this model seems to break, but it's just the model telling him, hey, let sweat drip off the skin. That's all it was," Romps said. "Just let the sweat drop off the skin."

That and a few other tweaks to Steadman's equations yielded an extended heat index that agrees with the old heat index 99.99% of the time, Romps said, but also accurately represents the apparent temperature for regimes outside those Steadman originally calculated. When he originally published his apparent temperature scale, he considered these regimes too rare to worry about, but high temperatures and humidities are becoming increasingly common because of climate change.

Romps and Lu had published the revised heat index equation earlier this year. In the most recent paper, they apply the extended heat index to the top 100 heat waves that occurred between 1984 and 2020. The researchers find mostly minor disagreements with what the NWS reported at the time, but also some extreme situations where the NWS heat index was way off.

One surprise was that seven of the 10 most physiologically stressful heat waves over that time period were in the Midwest—mostly in Illinois, Iowa and Missouri—not the Southeast, as meteorologists assumed. The largest discrepancies between the NWS heat index and the extended heat index were seen in a wide swath, from the Great Lakes south to Louisiana.

During the July 1995 heat wave in Chicago, for example, which killed at least 465 people, the maximum heat index reported by the NWS was 135 F, when it actually felt like 154 F. The revised heat index at Midway Airport, 141 F, implies that people in the shade would have experienced blood flow to the skin that was 170% above normal. The heat index reported at the time, 124 F, implied only a 90% increase in skin blood flow. At some places during the heat wave, the extended heat index implies that people would have experienced an increase of 820% above normal skin blood flow.

"I'm no physiologist, but a lot of things happen to the body when it gets really hot," Romps said. "Diverting blood to the skin stresses the system because you're pulling blood that would otherwise be sent to internal organs and sending it to the skin to try to bring up the skin's temperature. The approximate calculation used by the NWS, and widely adopted, inadvertently downplays the health risks of severe heat waves."

Physiologically, the body starts going haywire when the skin temperature rises to equal the body's core temperature, typically taken as 98.6 F. After that, the core temperature begins to increase. The maximum sustainable core temperature is thought to be 107 F—the threshold for heat death. For the healthiest of individuals, that threshold is reached at a heat index of 200 F.

Luckily, humidity tends to decrease as temperature increases, so Earth is unlikely to reach those conditions in the next few decades. Less extreme—though still deadly—conditions are nevertheless becoming common around the globe.

"A 200 F heat index is an upper bound of what is survivable," Romps said. "But now that we've got this model of human thermoregulation that works out at these conditions, what does it actually mean for the future habitability of the United States and the planet as a whole? There are some frightening things we are looking at." + Verder verkennen

Hot and getting hotter:Five essential reads on high temps and human bodies

Machine-learning maakt een voorheen ongeziene kijk op polymeren die nuttig zijn op biomedisch gebied mogelijk

Machine-learning maakt een voorheen ongeziene kijk op polymeren die nuttig zijn op biomedisch gebied mogelijk Zelfgemaakte lijm uit melk maken voor een wetenschappelijk project

Zelfgemaakte lijm uit melk maken voor een wetenschappelijk project Zilver verbetert de efficiëntie van monograinlaagzonnecellen

Zilver verbetert de efficiëntie van monograinlaagzonnecellen Hoe de atomaire structuur van Helium

Hoe de atomaire structuur van Helium Een eencijferige houten luidspreker met een dikte van één micrometer

Een eencijferige houten luidspreker met een dikte van één micrometer

Biologisch afbreekbaar alternatief ter vervanging van microplastics in cosmetica en toiletartikelen

Biologisch afbreekbaar alternatief ter vervanging van microplastics in cosmetica en toiletartikelen Lachgas, een broeikasgas, zit in de lift:studeren

Lachgas, een broeikasgas, zit in de lift:studeren De soorten slangen gevonden in Oost-Tennessee

De soorten slangen gevonden in Oost-Tennessee Het verwijderen van plastic zwerfvuil op zee is kostbaar voor kleine eilandstaten

Het verwijderen van plastic zwerfvuil op zee is kostbaar voor kleine eilandstaten Euraziatische instorting ijskap verhoogde zeeën acht meter:studie

Euraziatische instorting ijskap verhoogde zeeën acht meter:studie

Hoofdlijnen

- Paring induceert seksuele remming bij vrouwelijke springspinnen

- Ingenieurs hacken celbiologie om 3D-vormen te maken van levend weefsel

- Klonten als tijdelijke opslag

- Alles-in-één reparatiekit maakt CRISPR-genbewerking nauwkeuriger

- Lovelorn koala gepakt na ontsnapping uit dierentuin op jacht naar partner

- Laat me je bladeren zien - Gezondheidscontrole voor stadsbomen

- 5 manieren waarop je hersenen je emoties beïnvloeden

- Zijn getrouwde mensen gelukkiger dan alleenstaanden?

- Is het Ida-fossiel de ontbrekende schakel?

- NASA vindt een piekerige, door de wind geschoren tropische depressie 06W

- Uitgebreid onderzoeken wat de dinosauriërs heeft gedood

- Het is geen aurora, zijn STEVE

- Palmoliecertificering levert gemengde resultaten op voor naburige gemeenschappen

- Reservoirbeheer verandert de overstromingsfrequentie op regionale schaal

Levenscyclusanalyse gebruiken om de impact op het klimaat te verminderen

Levenscyclusanalyse gebruiken om de impact op het klimaat te verminderen Technologie maakt brandstofcellen krachtiger, duurzamer, minder duur

Technologie maakt brandstofcellen krachtiger, duurzamer, minder duur Artemis:hoe het steeds veranderende Amerikaanse ruimtebeleid de volgende maanlanding kan terugdringen

Artemis:hoe het steeds veranderende Amerikaanse ruimtebeleid de volgende maanlanding kan terugdringen 3D-printen echt 3D maken

3D-printen echt 3D maken Oprichter van India's belegerde Jet Airways neemt ontslag

Oprichter van India's belegerde Jet Airways neemt ontslag Klimaatbesprekingen moeten van mislukking worden gered, waarschuwt VN-chef

Klimaatbesprekingen moeten van mislukking worden gered, waarschuwt VN-chef Fairtrade-deals bieden vangnet voor Ivoriaanse cacaoproducenten

Fairtrade-deals bieden vangnet voor Ivoriaanse cacaoproducenten Strandresorts in Egypte bestrijden wereldwijde plaag van plastic afval

Strandresorts in Egypte bestrijden wereldwijde plaag van plastic afval

- Elektronica

- Biologie

- Zonsverduistering

- Wiskunde

- French | Italian | Spanish | Portuguese | Swedish | German | Dutch | Danish | Norway |

-

Wetenschap © https://nl.scienceaq.com