Wetenschap

Heeft democratie een aparte oorsprong in Amerika?

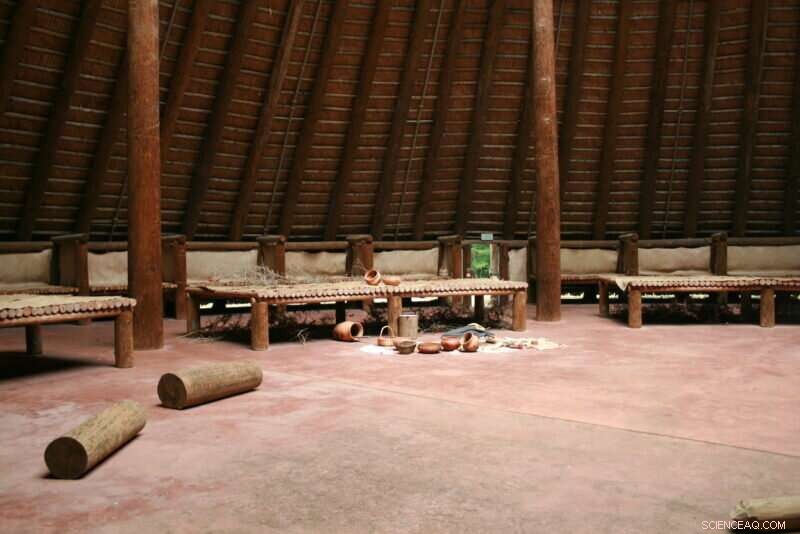

Inheemse gemeentehuizen (zoals dit gereconstrueerde voorbeeld in Mission San Luis de Apalachee in Tallahassee, Florida) waren de locatie van openbare bijeenkomsten en ceremonies voor vroege Amerikaanse gemeenschappen, en het bewijs daarvoor is op veel locaties in het zuidoosten gevonden. Credit:UGA Laboratorium voor Archeologie

Algemeen wordt aangenomen dat democratie ongeveer 2500 jaar geleden in de mediterrane wereld is ontstaan voordat ze zich via cultureel contact naar andere delen van de wereld verspreidde. Maar nieuw onderzoek van het Laboratorium voor Archeologie van de Universiteit van Georgia, samen met zijn partners in de Muscogee Nation, geeft aan dat inwoners van Amerika mogelijk al minstens een millennium vóór Europees contact democratisch collectief bestuur praktiseerden.

Volgens een nieuw artikel gepubliceerd in het tijdschrift American Antiquity , wijzen artefacten van de Cold Springs-site in centraal Georgië op de aanwezigheid van een "raadshuis" op de site, die ongeveer 1500 jaar geleden werd bewoond, volgens radiokoolstofdatering. Nog steeds in gebruik door afstammelingen van die vroege Amerikaanse gemeenschappen, waren raadshuizen grote, cirkelvormige structuren die plaats konden bieden aan honderden, zelfs duizenden deelnemers aan geritualiseerde bijeenkomsten waarbij collectieve besluitvorming betrokken was.

De Iroquois Confederatie, een bond van vijf inheemse naties die woonachtig zijn in wat het noordoosten van de Verenigde Staten zou worden, wordt beschouwd als een voorbeeld van een vroege Amerikaanse democratie. Sommige archeologen dateren de opkomst van de Iroquois Confederatie echter pas in het midden van de 15e eeuw, slechts enkele decennia vóór Europees contact. Op basis van de analyse van de Cold Springs-materialen suggereert het UGA-team dat democratische instellingen die verband houden met collectief bestuur veel eerder zijn ontstaan.

"De belangrijkste conclusie is dat dit soort democratische instellingen zeer lang bestond en bestond - misschien al millennia - vóór de komst van Europa", zegt Victor Thompson, Distinguished Research Professor en directeur van het Laboratorium voor Archeologie. "Dat is een heel ander perspectief op het inheemse bestuur in deze regio dan de meeste archeologen hebben."

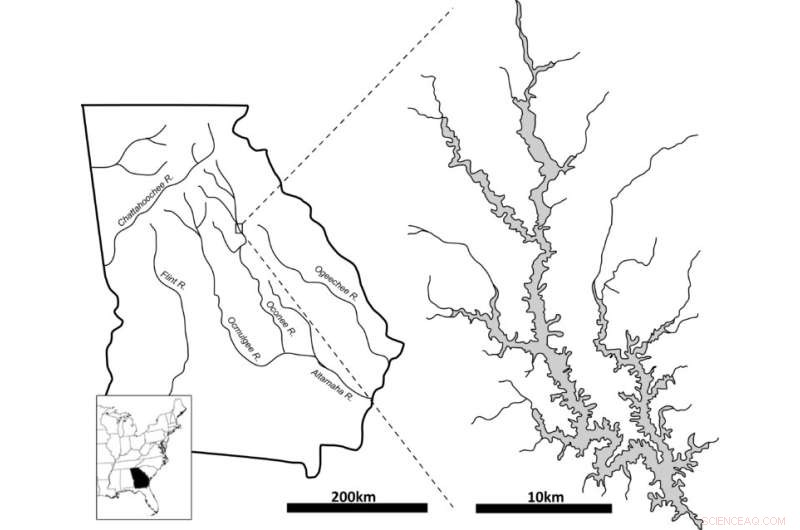

De Cold Springs-site, ongeveer 120 kilometer ten oosten van Atlanta, was gedeeltelijk ondergedompeld in wat nu Lake Oconee is toen de Oconee-rivier in de jaren zeventig werd afgedamd. Sinds de opgraving van de site bijna 50 jaar geleden, waren de artefacten van Cold Springs gearchiveerd in de collecties van het Laboratorium voor Archeologie totdat het UGA-team ze opnieuw onderzocht met nieuwe interesse en nieuwe technologieën. Credit:UGA Laboratorium voor Archeologie

Historisch gezien, zei Thompson, is de interpretatie van gemeentehuizen gekoppeld aan die van aarden platformheuvels; concentrische cirkels van paalgaten, het veelbetekenende archeologische bewijs voor gemeentehuizen, zijn vaak gevonden in de buurt van of bovenop terpen. Over the centuries since European arrival, a consensus emerged that, up until about 1,000 years ago, mounds and houses were purely ceremonial in purpose and constructed by largely egalitarian peoples, but at one point they suddenly transformed into political structures dominated by the village "chief."

"[The predominant view holds that] prior to 1,000 A.D., platform mounds are communal and they're built by these societies that don't have chiefs or anything like that," Thompson said. "But as soon as 1,000 A.D. hits, everyone has a chief, and the chief lives on top of the platform. Very convenient. Our new work adds more depth to this perspective and sheds light on the fact that while different positions existed in these governmental structures it is vastly more complicated, and democratic, than the traditional models posed by archaeologists since the 1970s."

Indeed, ever since Spanish explorers reported the first eyewitness accounts, indigenous American cultures have been portrayed as chiefdoms, led by autocratic-style individuals imbued with significant power over their people. However, according to UGA's tribal partners, this view conflicts with the forms of collective governance they still practice today and which, tradition has taught them, long predate the arrival of Europeans.

"We still have a National Council in our council house, which meets within it and passes national laws—it's been this way for hundreds of generations," said Turner Hunt, preservation officer for Muscogee (Creek) Nation and a co-author on the paper. "[The idea of chiefdoms] is a nuisance, and it's a grand narrative that's been very hard to overcome."

Today the Cold Springs site lies partially submerged by Lake Oconee, a human-made reservoir about 75 miles east of Atlanta. The site was excavated in the early 1970s prior to completion of the dam on the Oconee River that created the lake. For their current research, Thompson and his colleagues reexamined artifacts from that dig that have been in the Laboratory of Archaeology's collections for nearly 50 years.

Also referred to as rotundas or townhouses depending on the region, council houses often had highly structured seating arrangements denoting rank and status, as well as painted histories of the community on their walls. Credit:UGA Laboratory of Archaeology

"That's the beauty of museum collections," Thompson said. "They've just been sitting there, and they can tell you so much. All it really takes is new ideas, new methods, to be able to go back and look at these collections again."

The researchers performed new radiocarbon dating on the existing physical artifacts—44 new dates in all, which make Cold Springs now one of the best-dated early mound sites in the Southeast. The testing placed primary occupation of the site between A.D. 500 and 700, with construction of the council house beginning sometime around 500 A.D. As Thompson and his colleagues sifted through artifacts and other evidence, they stayed in continual contact with their Muscogee partners in Oklahoma.

"We were meeting on Zoom and looking at pictures of post holes—tons of pictures of post holes," said RaeLynn Butler, manager of the Historic and Cultural Preservation Department for the Muscogee Nation. "Our major contributions were to digest the information and provide the traditional knowledge and perspectives as tribal people that helped bring to this research some much-needed context of our social organization and traditional forms of government."

At the end of the day, both Hunt and Butler said, they hope to emphasize that sites like Cold Springs are not removed from contemporary society in a way similar to Stonehenge or the pyramids of Egypt. They are not relics of long-dead cultures with only historical or archaeological relevance.

"This is a paper about Ancestral Muskogean institutions, but there is a living, active culture that is directly connected to it," Hunt said. "We believe our governments, our democratic institutions, have been practicing this way of life for thousands of years. We are connected to these people through the way we still conduct ourselves today."

NASA ziet krachtige tropische cycloon Enawo Madagascar bedreigen

NASA ziet krachtige tropische cycloon Enawo Madagascar bedreigen Verwacht een bovengemiddeld Atlantisch orkaanseizoen, Amerikaanse voorspellers zeggen:

Verwacht een bovengemiddeld Atlantisch orkaanseizoen, Amerikaanse voorspellers zeggen: Nieuw model voor het evalueren van lanceringen van rangeland-systemen

Nieuw model voor het evalueren van lanceringen van rangeland-systemen Dagelijkse regenval boven Sumatra gekoppeld aan groter atmosferisch fenomeen

Dagelijkse regenval boven Sumatra gekoppeld aan groter atmosferisch fenomeen Te veel eten en wegwerpmentaliteit verminderen de wereldwijde voedselzekerheid en schaden het milieu

Te veel eten en wegwerpmentaliteit verminderen de wereldwijde voedselzekerheid en schaden het milieu

Hoofdlijnen

- Wat is Ceramide?

- Luipaard gevangen na 36 uur op jacht naar fabriek in India

- Honden likken hun mond om te communiceren met boze mensen

- Enzymen: wat is het? & Hoe werkt het?

- Ambtenaren:walvissen, na een dodelijk jaar, zou kunnen uitsterven

- De methoden van inventarisatie in Microbes

- Tagged slakken om onderzoekers te helpen de groei van de slakkenpopulatie te volgen

- Nieuwe genetische variatie van oude en exotische variëteiten voor milieuvriendelijke tarweteelt

- Nieuw onderzoek onthult de enige tuimelaars in Engeland

- Centurion hoofdgevechtstank

- Wiskundehoogleraar creëert kritische discussies rond COVID in nieuw boek

- Op ecologie gebaseerde economieën kunnen toekomstige catastrofes voorkomen

- Wat zorgde ervoor dat de torens van het World Trade Center op 9/11 instortten?

- Zorgen meditatiepodcasts en -apps voor authentiek boeddhisme?

Export van Zwitserse horloges blijft stijgen in april

Export van Zwitserse horloges blijft stijgen in april Opvouwbaar Motorola domineert patentbesprekingen als frissere comeback

Opvouwbaar Motorola domineert patentbesprekingen als frissere comeback Hoe Thermokoppelgevoeligheid te berekenen

Hoe Thermokoppelgevoeligheid te berekenen  Lichtgevende gammastraling gedetecteerd door de blazar DA 193

Lichtgevende gammastraling gedetecteerd door de blazar DA 193 Terrasvormig grafeen voor ultragevoelige magnetische veldsensor

Terrasvormig grafeen voor ultragevoelige magnetische veldsensor Ex-tropische cycloon Ann beweegt over het Australische schiereiland Cape York

Ex-tropische cycloon Ann beweegt over het Australische schiereiland Cape York Medische richtlijnen voor astronauten die in de VS worden gelanceerd

Medische richtlijnen voor astronauten die in de VS worden gelanceerd De meren verdrievoudigen de hoeveelheid koolstof die ze begraven als reactie op de menselijke verstoring van de wereldwijde nutriëntenkringlopen

De meren verdrievoudigen de hoeveelheid koolstof die ze begraven als reactie op de menselijke verstoring van de wereldwijde nutriëntenkringlopen

- Elektronica

- Biologie

- Zonsverduistering

- Wiskunde

- French | Italian | Spanish | Portuguese | Swedish | German | Dutch | Danish | Norway |

-

Wetenschap © https://nl.scienceaq.com