Wetenschap

Overgang van water naar land bij vroege tetrapoden

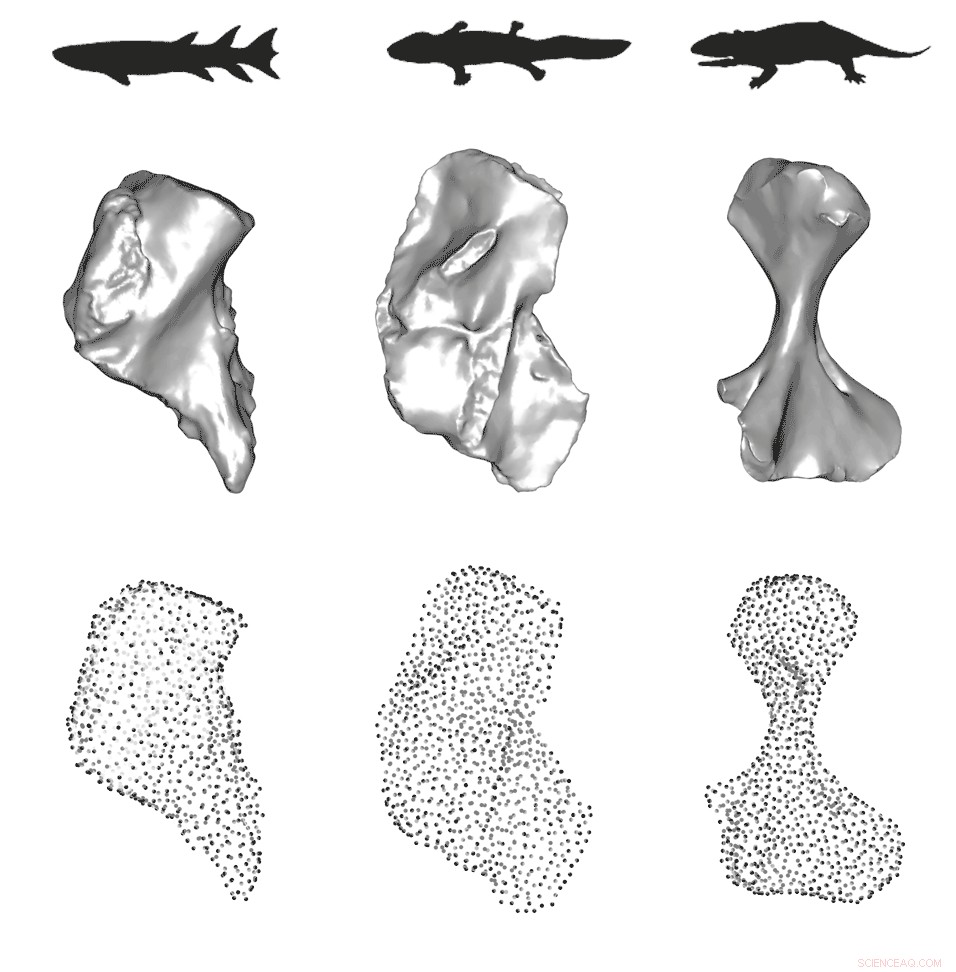

Drie belangrijke stadia van de evolutie van de humerusvorm:van de geblokte humerus van watervissen, naar de L-vormige humerus van overgangs-tetrapoden, en de gedraaide humerus van terrestrische tetrapoden. Kolommen (van links naar rechts) =watervissen, tijdelijke tetrapod, en terrestrische tetrapoden. Rijen =Boven:silhouetten van uitgestorven dieren; Midden:3D humerusfossielen; Onder:oriëntatiepunten die worden gebruikt om de vorm te kwantificeren. Krediet:Blake Dickson

De overgang van water naar land is een van de belangrijkste en meest inspirerende overgangen in de evolutie van gewervelde dieren. En de vraag hoe en wanneer tetrapoden overgingen van water naar land, is al lang een bron van verwondering en wetenschappelijk debat.

Vroege ideeën stelden dat opdrogende poelen van water vissen op het land strandden en dat het uit het water zijn de selectieve druk verschafte om meer ledematenachtige aanhangsels te ontwikkelen om terug naar het water te lopen. In de jaren negentig suggereerden nieuw ontdekte exemplaren dat de eerste tetrapoden veel aquatische kenmerken behielden, als kieuwen en een staartvin, en dat ledematen mogelijk in het water zijn geëvolueerd voordat tetrapoden zich aanpasten aan het leven op het land. Er is, echter, nog steeds onzekerheid over wanneer de overgang van water naar land plaatsvond en hoe terrestrische vroege tetrapoden werkelijk waren.

Een paper gepubliceerd op 25 november in Natuur behandelt deze vragen met behulp van fossiele gegevens met een hoge resolutie en laat zien dat hoewel deze vroege tetrapoden nog steeds aan water waren gebonden en aquatische kenmerken hadden, ze hadden ook aanpassingen die wijzen op enig vermogen om op het land te bewegen. Hoewel, ze waren er misschien niet zo goed in, althans naar de huidige maatstaven.

Hoofdauteur Blake Dickson, doctoraat '20 in de afdeling Organismische en Evolutionaire Biologie aan de Harvard University, en senior auteur Stephanie Pierce, Thomas D. Cabot Universitair hoofddocent bij de afdeling Organismic and Evolutionary Biology en curator van paleontologie van gewervelde dieren in het Museum of Comparative Zoology aan de Harvard University, onderzocht 40 driedimensionale modellen van fossiele humeri (bovenarmbeen) van uitgestorven dieren die de overgang van water naar land overbruggen.

"Omdat het fossielenbestand van de overgang naar land in tetrapoden zo slecht is, gingen we naar een bron van fossielen die de volledige overgang van een volledig aquatische vis naar een volledig terrestrische tetrapod beter zou kunnen vertegenwoordigen, ' zei Dickson.

Tweederde van de fossielen kwam uit de historische collecties die zijn ondergebracht in het Museum of Comparative Zoology van Harvard, die afkomstig zijn van over de hele wereld. Om de ontbrekende gaten op te vullen, Pierce reikte contact met collega's met belangrijke exemplaren uit Canada, Schotland, en Australië. Van belang voor de studie waren nieuwe fossielen die onlangs werden ontdekt door co-auteurs Dr. Tim Smithson en professor Jennifer Clack, Universiteit van Cambridge, VK, als onderdeel van het TW:eed-project, een initiatief dat is ontworpen om de vroege evolutie van landgaande tetrapoden te begrijpen.

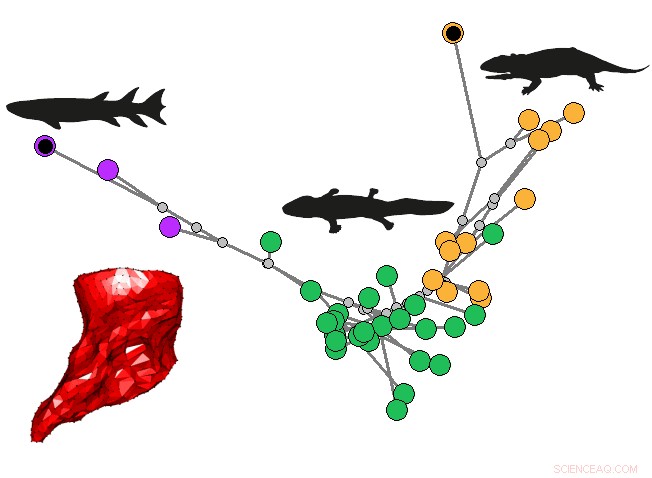

Het evolutionaire pad en de vorm veranderen van een opperarmbeen van een aquatische vis in een terrestrische tetrapod-opperarmbeen. Krediet:Blake Dickson.

De onderzoekers kozen voor het humerusbot omdat het niet alleen overvloedig en goed bewaard is gebleven in het fossielenarchief, maar het is ook aanwezig in alle sarcopterygiërs - een groep dieren die coelacanth-vissen omvat, longvis, en alle tetrapoden, inclusief al hun fossiele vertegenwoordigers. "We verwachtten dat de humerus een sterk functioneel signaal zou dragen als de dieren overgingen van een volledig functionele vis naar volledig terrestrische tetrapoden, en dat we dat konden gebruiken om te voorspellen wanneer tetrapoden zich op het land begonnen te verplaatsen, " zei Pierce. "We ontdekten dat aardse vaardigheden samenvallen met de oorsprong van ledematen, dat is echt spannend."

De humerus verankert het voorbeen op het lichaam, herbergt veel spieren, en moet veel stress kunnen weerstaan tijdens beweging op basis van ledematen. Daarom, het bevat veel kritische functionele informatie met betrekking tot de beweging en ecologie van een dier. Researchers have suggested that evolutionary changes in the shape of the humerus bone, from short and squat in fish to more elongate and featured in tetrapods, had important functional implications related to the transition to land locomotion. This idea has rarely been investigated from a quantitative perspective—that is, tot nu.

When Dickson was a second-year graduate student, he became fascinated with applying the theory of quantitative trait modeling to understanding functional evolution, a technique pioneered in a 2016 study led by a team of paleontologists and co-authored by Pierce. Central to quantitative trait modeling is paleontologist George Gaylord Simpson's 1944 concept of the adaptive landscape, a rugged three-dimensional surface with peaks and valleys, like a mountain range. On this landscape, increasing height represents better functional performance and adaptive fitness, and over time it is expected that natural selection will drive populations uphill towards an adaptive peak.

Dickson and Pierce thought they could use this approach to model the tetrapod transition from water to land. They hypothesized that as the humerus changed shape, the adaptive landscape would change too. Bijvoorbeeld, fish would have an adaptive peak where functional performance was maximized for swimming and terrestrial tetrapods would have an adaptive peak where functional performance was maximized for walking on land. "We could then use these landscapes to see if the humerus shape of earlier tetrapods was better adapted for performing in water or on land" said Pierce.

"We started to think about what functional traits would be important to glean from the humerus, " said Dickson. "Which wasn't an easy task as fish fins are very different from tetrapod limbs." In the end, they narrowed their focus on six traits that could be reliably measured on all of the fossils including simple measurements like the relative length of the bone as a proxy for stride length and more sophisticated analyses that simulated mechanical stress under different weight bearing scenarios to estimate humerus strength.

"If you have an equal representation of all the functional traits you can map out how the performance changes as you go from one adaptive peak to another, " Dickson explained. Using computational optimization the team was able to reveal the exact combination of functional traits that maximized performance for aquatic fish, terrestrial tetrapods, and the earliest tetrapods. Their results showed that the earliest tetrapods had a unique combination of functional traits, but did not conform to their own adaptive peak.

"What we found was that the humeri of the earliest tetrapods clustered at the base of the terrestrial landscape, " said Pierce. "indicating increasing performance for moving on land. But these animals had only evolved a limited set of functional traits for effective terrestrial walking."

The researchers suggest that the ability to move on land may have been limited due to selection on other traits, like feeding in water, that tied early tetrapods to their ancestral aquatic habitat. Once tetrapods broke free of this constraint, the humerus was free to evolve morphologies and functions that enhanced limb-based locomotion and the eventual invasion of terrestrial ecosystems

"Our study provides the first quantitative, high-resolution insight into the evolution of terrestrial locomotion across the water-land transition, " said Dickson. "It also provides a prediction of when and how [the transition] happened and what functions were important in the transition, at least in the humerus."

"Moving forward, we are interested in extending our research to other parts of the tetrapod skeleton, " Pierce said. "For instance, it has been suggested that the forelimbs became terrestrially capable before the hindlimbs and our novel methodology can be used to help test that hypothesis."

Dickson recently started as a Postdoctoral Researcher in the Animal Locomotion lab at Duke University, but continues to collaborate with Pierce and her lab members on further studies involving the use of these methods on other parts of the skeleton and fossil record.

Onderweg lithiumionen achtervolgen in een snelladende batterij

Onderweg lithiumionen achtervolgen in een snelladende batterij Op Mars of de aarde, biohybride kan koolstofdioxide omzetten in nieuwe producten

Op Mars of de aarde, biohybride kan koolstofdioxide omzetten in nieuwe producten Water verandert hoe een op kobalt gebaseerd molecuul koolstofdioxide omzet in een veelbelovende chemische stof

Water verandert hoe een op kobalt gebaseerd molecuul koolstofdioxide omzet in een veelbelovende chemische stof Hit-to-lead-onderzoeken naar een nieuwe reeks kleine molecuulremmers van DHODH

Hit-to-lead-onderzoeken naar een nieuwe reeks kleine molecuulremmers van DHODH Theoretici bewijzen eindelijk dat gekrulde pijlen de waarheid vertellen over chemische reacties

Theoretici bewijzen eindelijk dat gekrulde pijlen de waarheid vertellen over chemische reacties

Vulkaanuitbarstingen hadden het afgelopen millennium grote en aanhoudende gevolgen voor het wereldwijde hydroklimaat

Vulkaanuitbarstingen hadden het afgelopen millennium grote en aanhoudende gevolgen voor het wereldwijde hydroklimaat Guatemala-redders haasten zich om de laatste vulkaanoverlevenden te vinden

Guatemala-redders haasten zich om de laatste vulkaanoverlevenden te vinden Sociaal-economisch, milieueffecten van COVID-19 gekwantificeerd

Sociaal-economisch, milieueffecten van COVID-19 gekwantificeerd Verzuring van de oceaan treft krabvisserij West Coast Dungeness, nieuwe beoordeling toont

Verzuring van de oceaan treft krabvisserij West Coast Dungeness, nieuwe beoordeling toont Factoren van ecologische successie

Factoren van ecologische successie

Hoofdlijnen

- Alles in de familie:gerichte genomische vergelijkingen

- Hoe beïnvloeden Genotype en Fenotype hoe je eruit ziet?

- Orkaan verscheurde het gerenommeerde onderzoekscentrum van Monkey Island

- Wat is het Malthusiaanse uitgangspunt?

- Lijst met ingekapselde bacteriën

- Hoe de griezelige verkenningen van de zomer

- Campylobacter gebruikt andere organismen als Trojaans paard om nieuwe gastheren te infecteren

- Ziektekiemen kunnen onze persoonlijkheid helpen vormen

- Waarom creëren Britse wetenschappers een hybride mens-varken?

Wat is Interquartile in Math?

Wat is Interquartile in Math?  Welke soorten dieren leven in de staat Californië?

Welke soorten dieren leven in de staat Californië?  Verschillende soorten licht creëren met manipuleerbare kwantumeigenschappen

Verschillende soorten licht creëren met manipuleerbare kwantumeigenschappen Bevestiging van een bron van het proces achter poollicht en de vorming van sterren

Bevestiging van een bron van het proces achter poollicht en de vorming van sterren Instagram-test van het verbergen van likes die zich naar de VS verspreiden

Instagram-test van het verbergen van likes die zich naar de VS verspreiden Luchtkwaliteitsmetingen:nieuwe productiemethode voor nanogassensoren opent deuren

Luchtkwaliteitsmetingen:nieuwe productiemethode voor nanogassensoren opent deuren Ruby Vs. Rubellite

Ruby Vs. Rubellite Grand Canyon test verandering in watersysteem voor bezoekers (update)

Grand Canyon test verandering in watersysteem voor bezoekers (update)

- Elektronica

- Biologie

- Zonsverduistering

- Wiskunde

- French | Italian | Spanish | Portuguese | Swedish | German | Dutch | Danish | Norway |

-

Wetenschap © https://nl.scienceaq.com