Wetenschap

Wetenschappers bieden bedrijven een nieuwe chemie voor groener polyurethaan

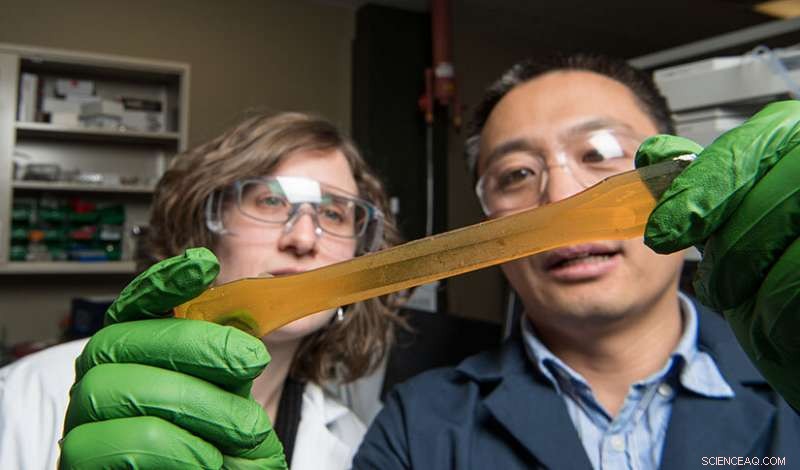

Een baanbrekende hernieuwbare formule - NREL-onderzoeker Tao Dong (rechts) en voormalig stagiair Stephanie Federle (links) onderzoeken biogebaseerde, niet-toxische polyurethaanhars, een veelbelovend alternatief voor conventioneel polyurethaan. Krediet:Dennis Schroeder, NREL

Zonder het, de wereld is misschien een beetje minder zacht en een beetje minder warm. Onze recreatieve kleding kan minder water afstoten. De inlegzolen in onze sneakers bieden mogelijk niet dezelfde therapeutische ondersteuning van de voetboog. De houtnerf in afgewerkte meubels "knalt" misschien niet.

Inderdaad, polyurethaan - een veelgebruikt plastic in toepassingen variërend van spuitbare schuimen tot kleefstoffen tot synthetische kledingvezels - is een hoofdbestanddeel van de 21e eeuw geworden, gemak toevoegen, comfort, en zelfs schoonheid tot tal van aspecten van het dagelijks leven.

De enorme veelzijdigheid van het materiaal, die momenteel grotendeels wordt gemaakt van aardoliebijproducten, heeft van polyurethaan het go-to-plastic gemaakt voor een reeks producten. Vandaag, Jaarlijks wordt er wereldwijd meer dan 16 miljoen ton polyurethaan geproduceerd.

"Er zijn maar weinig aspecten van ons leven die niet worden aangeraakt door polyurethaan, ’ weerspiegelde Phil Pienkos, een chemicus die onlangs met pensioen ging bij het National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) na bijna 40 jaar onderzoek.

Maar Pienkos - die een carrière opbouwde in het onderzoeken van nieuwe manieren om biogebaseerde brandstoffen en materialen te produceren - zei dat er een groeiende druk is om te heroverwegen hoe polyurethaan wordt geproduceerd.

"De huidige methoden zijn grotendeels afhankelijk van giftige chemicaliën en niet-hernieuwbare aardolie, " zei hij. "We wilden een nieuw plastic ontwikkelen met alle nuttige eigenschappen van conventioneel poly, maar zonder de kostbare bijwerkingen voor het milieu."

Was het mogelijk? Resultaten van het laboratorium geven een volmondig ja.

Door een nieuwe chemie met behulp van niet-toxische bronnen zoals lijnolie, afval vet, of zelfs algen, Pienkos en zijn NREL-collega Tao Dong, een expert in chemische technologie, hebben een baanbrekende methode ontwikkeld voor de productie van hernieuwbaar polyurethaan zonder giftige voorlopers.

Het is een doorbraak met het potentieel om de markt groener te maken voor producten variërend van schoenen, aan auto's, naar matrassen, en verder.

Maar om het enorme gewicht van de prestatie te begrijpen, het is nuttig om terug te kijken naar hoe de wetenschappelijke vooruitgang tot stand kwam, een verhaal dat afdwaalt van de chemische fundamenten van conventioneel polyurethaan, naar het algenlab waar een idee voor een nieuwe chemie ontstond, en baant zich een weg naar nieuwe zakelijke partnerschappen die de weg vrijmaken voor een veelbelovende toekomst van commercialisering.

Een kwestie van scheikunde

Toen polyurethaan in de jaren vijftig voor het eerst op de markt kwam, het groeide snel in populariteit voor gebruik in tal van producten en toepassingen. Dat was niet in de laatste plaats te danken aan de dynamische en afstembare eigenschappen van het materiaal, evenals de beschikbaarheid en betaalbaarheid van de op aardolie gebaseerde componenten die worden gebruikt om het te maken.

Door een slim chemisch proces met behulp van polyolen en isocyanaten - de basisbouwstenen van conventionele polyurethanen - konden fabrikanten hun formuleringen aanpassen om een verbluffende verscheidenheid aan polyurethaanmaterialen te produceren, elk met unieke en nuttige eigenschappen.

Geproduceerd uit een polyol met lange keten, bijvoorbeeld, kan flexibel schuim opleveren voor een zachte matras. Een andere formulering kan een rijke vloeistof opleveren die, wanneer uitgespreid op meubels, zowel beschermt als onthult de inherente schoonheid van houtnerf. Een derde batch kan kooldioxide (CO 2 ) om het materiaal uit te breiden, het produceren van een spuitbaar schuim dat opdroogt tot stijve en poreuze isolatie, perfect om warmte vast te houden in huis.

"Dat is het mooie van isocyanaat, " zei Dong toen hij nadacht over conventioneel polyurethaan, "zijn vermogen om schuim te vormen."

Maar Dong zei dat isocyanaten aanzienlijke nadelen met zich meebrengen, te. Hoewel deze chemicaliën een hoge reactiviteit hebben, waardoor ze zeer geschikt zijn voor vele industriële toepassingen, ze zijn ook zeer giftig, en ze worden geproduceerd uit een nog giftiger grondstof, fosgeen. Bij inademing, isocyanaten kunnen leiden tot een reeks nadelige gezondheidseffecten, zoals huid, oog, en keelirritatie, astma, en andere ernstige longproblemen.

"Als producten met conventionele polyurethanen worden verbrand, die isocyanaten vervluchtigen en komen vrij in de atmosfeer, " Pienkos toegevoegd. Zelfs gewoon polyurethaan spuiten voor gebruik als isolatie, Pienkos zei, kan isocyanaat vernevelen, werknemers verplichten om zorgvuldige voorzorgsmaatregelen te nemen om hun gezondheid te beschermen.

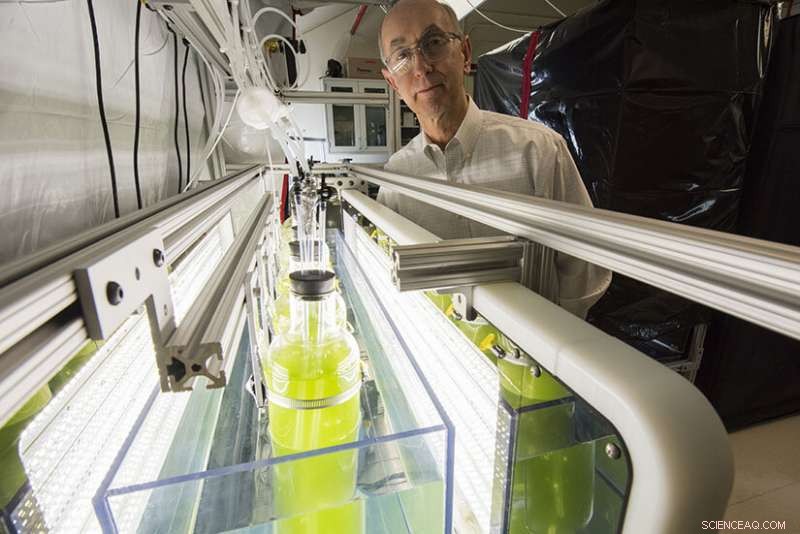

Onlangs met pensioen, Phil Pienkos (foto) richtte een nieuw bedrijf op, Polaris hernieuwbare energiebronnen, om de commercialisering van het nieuwe polyurethaan te helpen versnellen, an idea that originally grew out of his algae biofuel research at NREL. Krediet:Dennis Schroeder, NREL

To try and tackle these and other issues—such as reliance on petrochemicals—scientists from labs around the world have begun looking for new ways to synthesize polyurethane using bio-based resources. But these efforts have largely had mixed results. Some lacked the performance needed for industry applications. Others were not completely renewable.

The challenge to improve polyurethane, dan, remained ripe for innovation.

"We can do better than this, " thought Pienkos five years ago when he first encountered the predicament. Energized by the opportunity, he joined with Dong and Lieve Laurens, also of NREL, on a search for a better polyurethane chemistry.

Rethinking the Building Blocks of Polyurethane

The idea grew from a seemingly unrelated laboratory problem:lowering the cost of algae biofuels. As with many conventional petrochemical refining processes, biofuel refiners look for ways to use the coproducts of their processes as a source of revenue.

The question becomes much the same for algae biorefining. Can the waste lipids and amino acids from the process become ingredients for a prized recipe for polyurethane that is both renewable and nontoxic?

For Dong, answering the question at the basic chemical level was the easy part—of course they could. Scientists in the 1950s had shown it was possible to synthesize polyurethane from non-isocyanate pathways.

The real challenge, Dong said, was figuring out how to speed up that reaction to compete with conventional processes. He needed to produce polymers that performed at least as well as conventional materials, a major technical barrier to commercializing bio-based polyurethanes.

"The reactivity of the non-isocyanate, bio-based processes described in the literature is slower, " Dong explained. "So we needed to make sure we had reactivity comparable to conventional chemistry."

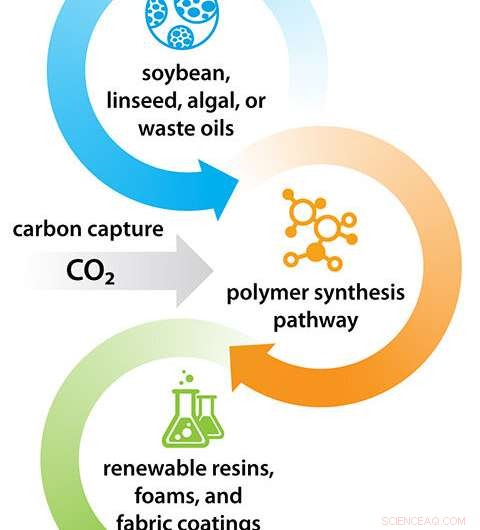

NREL's process overcomes the barrier by developing bio-based formulas through a clever chemical process. It begins with an epoxidation process, which prepares the base oil—anything from canola oil or linseed oil to algae or food waste—for further chemical reactions. By reacting these epoxidized fatty acids with CO 2 from the air or flue gas, carbonated monomers are produced. als laatste, Dong combines the carbonated monomers with diamines (derived from amino acids, another bio-based source) in a polymerization process that yields a material that cures into a resin—non-isocyanate polyurethane.

By replacing petroleum-based polyols with select natural oils, and toxic isocyanates with bio-based amino acids, Dong had managed to synthesize polymers with properties comparable to conventional polyurethane. Met andere woorden, he had developed a viable renewable, nontoxic alternative to conventional polyurethane.

And the chemistry had an added environmental benefit, te.

"As much of 30% by weight of the final polymer is CO 2 , " Pienkos said, adding that the numbers are even more impressive when considering the CO 2 absorbed by the plants or algae used to create the oils and amino acids in the first place.

CO 2 , a ubiquitous greenhouse gas, is often considered an unfortunate waste product of various industrial processes, prompting many companies to look for ways to absorb it, eliminate it, or even put it to good use as a potential source of profit. By incorporating CO 2 into the very structure of their polyurethane, Pienkos and Dong had provided a pathway for boosting its value.

"That means less raw material per pound of polymer, lagere kost, and a lower overall carbon footprint, " Pienkos continued. "It looks to us that this offers remarkable sustainability opportunities."

A Sought-After Renewable Solution Finds Its Commercial Feet

The next step was to see if the process could be commercialized, scaled up to meet the demands of the market.

The building blocks of poly—NREL's chemistry reacts natural oils with readily available carbon dioxide to produce renewable, nontoxic polyurethanes—a pathway for creating a variety of green materials and products. Credit:National Renewable Energy Laboratory

Ten slotte, renewable or not, polyurethane needs to demonstrate the properties that consumers expect from brand-name products. The process to create it must also match companies' manufacturing processes, allowing them to "drop in" the new material without prohibitively costly upgrades to facilities or equipment.

"That's why we need to work with industry partners, " Dong explained, "to make sure our research aligns with their manufacturing processes."

In the two short years since Pienkos and Dong first demonstrated the viability of producing fully renewable, nontoxic polyurethane, several companies have already contributed resources and research partnerships in the push for its commercialization.

A 2020 U.S. Department of Energy Technology Commercialization Fund award, bijvoorbeeld, brought in $730, 000 of federal funding to help develop the technology, as well as matching "in kind" cost share from the outdoor clothing company Patagonia, the mattress company Tempur Sealy, and a start-up biotechnology company called Algix.

And Pienkos says companies from other industries have shown preliminary interest, te. "These companies believe there is promise in this, " hij zei.

Their interest could partly be due to the tunability of Pienkos and Dong's approach, which lets them, much like conventional methods, create polymers that match industry standards.

"We've demonstrated that the chemistry is tunable, " Dong said. "We can control the final performance through our approach."

By controlling the epoxidation process or amount of carbonization, bijvoorbeeld, the process can be suited to meet the performance needs of a product. That may give the outsoles of a pair of running shoes enough flexibility and strength to endure many miles pounding into hot or cold asphalt. Or it may give a mattress a balance of stiffness and support.

"It's got regulation push. It's got market pull. It's got the potential to compete with non-renewables on the basis of cost. It's got a lower carbon footprint. It's got everything, " Pienkos said of the opportunities for commercialization. "This became the most exciting aspect of my career at NREL. Dus, when I retired, I decided that I want to make this real. I want to see this technology actually make it into the marketplace."

After retiring last April, Pienkos went on to establish a company, Polaris Renewables, to help accelerate the commercialization of the novel polyurethane. Dus, while he continues with his responsibilities as an NREL emeritus researcher, he is also doing outreach to industry to find additional corporate partners, especially in the fashion industry through the international sustainability initiative Fashion for Good.

"In the fashion industry, customers are demanding sustainability, " he explained. "They will pay something of a green premium if you can demonstrate a lower carbon footprint, better end of life disposition."

Inderdaad, for both Pienkos and Dong, the breakthrough in renewable, nontoxic polyurethane has become more than an exciting scientific venture. It offers the world a pathway for products that leave a lighter mark on the environment.

"I think this is a great opportunity to solve the plastic pollution problem, " Dong said. "We need to save our environment, and part of that begins with making plastic renewable."

Pienkos, te, thinks that a commercial success in this venture could be a catalyst that spurs further growth and further success in bringing renewable, greener products to the market.

"This could be a success story for NREL, " he said. "A success here means a great deal to the world."

In dit geval, success might be measured in more than the affordability of the production process or the carbon uptake of the polyurethane chemistry. In a world with NREL's renewable, nontoxic polyurethane, success might be something we can truly feel in the durability of our clothing, in the comfort our shoes provide, or in the rejuvenation we feel after sleeping on a memory foam mattress.

Hoofdlijnen

- Wat zijn de functies van Triglyceride Phospholipid & Sterol?

- Antropologen beschrijven derde orang-oetansoort

- Onderzoekers ontdekken hoe een aan microtubuli gerelateerd gen de neurale ontwikkeling beïnvloedt

- Wat is het belang van virtual reality voor artsen en chirurgen?

- Hoe beïnvloeden Genotype en Fenotype hoe je eruit ziet?

- Mannelijke mammoeten vielen vaker in natuurlijke vallen en stierven, DNA-bewijs suggereert:

- Pogingen om te vangen, red het bedreigde einde van de bruinvis in Mexico

- Science Fair Ideas With the Topic Dance

- Onderzoekers brengen het menselijk genoom in 4-D in kaart terwijl het vouwt

Wat is het spectrum van TL-licht?

Wat is het spectrum van TL-licht?  Ongebruikte gebouwen zullen goede huisvesting zijn in de wereld van COVID-19

Ongebruikte gebouwen zullen goede huisvesting zijn in de wereld van COVID-19 Dodental moesson India stijgt tot 159 tientallen nog vermist

Dodental moesson India stijgt tot 159 tientallen nog vermist Recycling van fotovoltaïsch afval stimuleert circulaire economie

Recycling van fotovoltaïsch afval stimuleert circulaire economie De sleutel tot het verminderen van de uitstoot van kooldioxide is gemaakt van metaal

De sleutel tot het verminderen van de uitstoot van kooldioxide is gemaakt van metaal Ingenieurs zetten tienduizenden kunstmatige hersensynapsen op een enkele chip

Ingenieurs zetten tienduizenden kunstmatige hersensynapsen op een enkele chip Toekomstige weersvoorspelling - het zit allemaal in de MRI van wolken

Toekomstige weersvoorspelling - het zit allemaal in de MRI van wolken Onderzoek test nieuwe methoden voor waterrecycling in de ruimte

Onderzoek test nieuwe methoden voor waterrecycling in de ruimte

- Elektronica

- Biologie

- Zonsverduistering

- Wiskunde

- French | Italian | Portuguese | Swedish | Dutch | Norway | Spanish | German | Danish |

-

Wetenschap © https://nl.scienceaq.com