Wetenschap

Altruïsme bij vogels? Eksters zijn wetenschappers te slim af geweest door elkaar te helpen trackingapparaten te verwijderen

Tegoed:Shutterstock

Toen we kleine, rugzakachtige volgapparatuur aan vijf Australische eksters bevestigden voor een pilotstudie, hadden we niet verwacht dat we een geheel nieuw sociaal gedrag zouden ontdekken dat zelden bij vogels wordt gezien.

Ons doel was om meer te leren over de beweging en sociale dynamiek van deze zeer intelligente vogels, en om deze nieuwe, duurzame en herbruikbare apparaten te testen. In plaats daarvan waren de vogels ons te slim af.

Zoals ons nieuwe onderzoeksartikel uitlegt, begonnen de eksters bewijs te vertonen van coöperatief "reddings" -gedrag om elkaar te helpen de tracker te verwijderen.

Hoewel we weten dat eksters intelligente en sociale wezens zijn, was dit de eerste keer dat we wisten dat dit soort schijnbaar altruïstisch gedrag vertoonde:een ander lid van de groep helpen zonder een onmiddellijke, tastbare beloning te krijgen.

Spannende nieuwe apparaten testen

Als academische wetenschappers zijn we eraan gewend dat experimenten op de een of andere manier mislopen. Vervallen stoffen, defecte apparatuur, besmette monsters, een ongeplande stroomuitval - dit kan allemaal maanden (of zelfs jaren) zorgvuldig gepland onderzoek vertragen.

Voor degenen onder ons die dieren bestuderen, en vooral gedrag, maakt onvoorspelbaarheid deel uit van de functieomschrijving. Dit is de reden waarom we vaak pilotstudies nodig hebben.

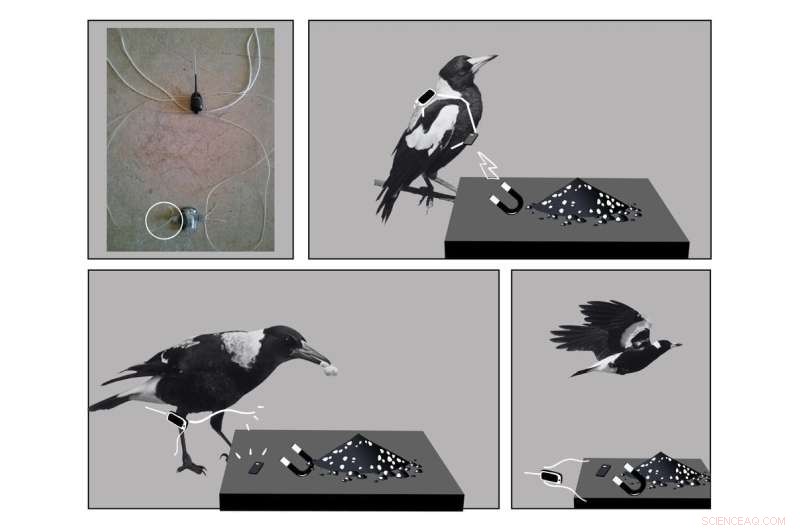

Een van de trackers die we hebben vastgemaakt aan vijf eksters, die minder dan één gram wegen. Krediet:Dominique Potvin, auteur verstrekt

Onze pilotstudie was een van de eerste in zijn soort:de meeste trackers zijn te groot om op middelgrote tot kleine vogels te passen, en degenen die dat wel doen, hebben meestal een zeer beperkte capaciteit voor gegevensopslag of levensduur van de batterij. Ze zijn ook meestal alleen voor eenmalig gebruik.

Een nieuw aspect van ons onderzoek was het ontwerp van het harnas dat de tracker vasthield. We bedachten een methode waarbij vogels niet opnieuw hoefden te worden gevangen om kostbare gegevens te downloaden of de kleine apparaten opnieuw te gebruiken.

We hebben een groep lokale eksters getraind om naar een "buitenstation" te komen dat de batterij van de tracker draadloos kan opladen, gegevens kan downloaden of de tracker en het harnas kan ontgrendelen met behulp van een magneet.

Het harnas was taai, met slechts één zwak punt waar de magneet kon functioneren. Om het harnas te verwijderen, had je die magneet nodig, of een heel goede schaar. We waren enthousiast over het ontwerp, omdat het veel mogelijkheden voor efficiëntie opende en veel gegevens kon verzamelen.

We wanted to see if the new design would work as planned, and discover what kind of data we could gather. How far did magpies go? Did they have patterns or schedules throughout the day in terms of movement, and socialising? How did age, sex or dominance rank affect their activities?

All this could be uncovered using the tiny trackers—weighing less than one gram—we successfully fitted five of the magpies with. All we had to do was wait, and watch, and then lure the birds back to the station to gather the valuable data.

It was not to be

Many animals that live in societies cooperate with one another to ensure the health, safety and survival of the group. In fact, cognitive ability and social cooperation has been found to correlate. Animals living in larger groups tend to have an increased capacity for problem solving, such as hyenas, spotted wrasse, and house sparrows.

Australian magpies are no exception. As a generalist species that excels in problem solving, it has adapted well to the extreme changes to their habitat from humans.

Australian magpies generally live in social groups of between two and 12 individuals, cooperatively occupying and defending their territory through song choruses and aggressive behaviors (such as swooping). These birds also breed cooperatively, with older siblings helping to raise young.

During our pilot study, we found out how quickly magpies team up to solve a group problem. Within ten minutes of fitting the final tracker, we witnessed an adult female without a tracker working with her bill to try and remove the harness off of a younger bird.

Within hours, most of the other trackers had been removed. By day 3, even the dominant male of the group had its tracker successfully dismantled.

We don't know if it was the same individual helping each other or if they shared duties, but we had never read about any other bird cooperating in this way to remove tracking devices.

Our new tracker design was innovative, allowing a magnet to release the harness. Credit:Dominique Potvin, Author provided

The birds needed to problem solve, possibly testing at pulling and snipping at different sections of the harness with their bill. They also needed to willingly help other individuals, and accept help.

The only other similar example of this type of behavior we could find in the literature was that of Seychelles warblers helping release others in their social group from sticky Pisonia seed clusters. This is a very rare behavior termed "rescuing."

Saving magpies

So far, most bird species that have been tracked haven't necessarily been very social or considered to be cognitive problem solvers, such as waterfowl and raptors. We never considered the magpies may perceive the tracker as some kind of parasite that requires removal.

Tracking magpies is crucial for conservation efforts, as these birds are vulnerable to the increasing frequency and intensity of heatwaves under climate change.

In a study published this week, Perth researchers showed the survival rate of magpie chicks in heatwaves can be as low as 10%.

Importantly, they also found that higher temperatures resulted in lower cognitive performance for tasks such as foraging. This might mean cooperative behaviors become even more important in a continuously warming climate.

Just like magpies, we scientists are always learning to problem solve. Now we need to go back to the drawing board to find ways of collecting more vital behavioral data to help magpies survive in a changing world.

pinMOS:nieuw geheugenapparaat kan optisch of elektrisch worden beschreven en uitgelezen

pinMOS:nieuw geheugenapparaat kan optisch of elektrisch worden beschreven en uitgelezen Wetenschappers ontwikkelen technologie om tumorcellen te vangen

Wetenschappers ontwikkelen technologie om tumorcellen te vangen De cryo-elektronenmicroscopiestructuur van huntingtine

De cryo-elektronenmicroscopiestructuur van huntingtine De kern van hoe uien je aan het huilen maken

De kern van hoe uien je aan het huilen maken Een goede zaak beter maken:een zuurtest die niet in water verdrinkt

Een goede zaak beter maken:een zuurtest die niet in water verdrinkt

Luchthavens op de Canarische Eilanden gaan weer open als de nevel optrekt

Luchthavens op de Canarische Eilanden gaan weer open als de nevel optrekt NASA-sneeuwcampagne loopt af voor 2021

NASA-sneeuwcampagne loopt af voor 2021 Geesten van gletsjers in het verleden wijzen op toekomstige klimaatuitdagingen

Geesten van gletsjers in het verleden wijzen op toekomstige klimaatuitdagingen EU sluit game changer-deal af en stelt CO2-reductiedoel vast

EU sluit game changer-deal af en stelt CO2-reductiedoel vast Australië lanceert droogteplan van miljard dollar

Australië lanceert droogteplan van miljard dollar

Hoofdlijnen

- Kunnen we leren om van slakken en slakken te houden in onze tuinen?

- Plantaardige hulpbronnen bedreigd door plagen en ziekten

- Onderzoekers identificeren combinatie van factoren voor biologische cacaoopbrengst

- Simpele microscoopexperimenten

- Hoe schimmel te identificeren in petrischalen

- Hoe maak je een werkend hart Model

- Studie toont aan dat boomspitsen evolutionaire regels overtreden

- Waar bevinden lipiden zich in het lichaam?

- Ademhaling bij planten en dieren

Post-Tropical Storm Teddy in nachtelijk zicht op NASA Newfoundland

Post-Tropical Storm Teddy in nachtelijk zicht op NASA Newfoundland Beheersing van warmte- en deeltjesstromen in nanodevices door kwantumobservatie

Beheersing van warmte- en deeltjesstromen in nanodevices door kwantumobservatie Verloren generatie? De crisis van 2008 weegt nog steeds op millennials

Verloren generatie? De crisis van 2008 weegt nog steeds op millennials Nieuwe tool om het ontdekken van medicijnen te versnellen

Nieuwe tool om het ontdekken van medicijnen te versnellen Simulaties suggereren dat geo-engineering de opwarming van de aarde niet zou stoppen als de broeikasgassen blijven toenemen

Simulaties suggereren dat geo-engineering de opwarming van de aarde niet zou stoppen als de broeikasgassen blijven toenemen Aankondiging van kwartet draadloze oplaadproducten voor thuis, kantoor, auto

Aankondiging van kwartet draadloze oplaadproducten voor thuis, kantoor, auto Nieuwe studie toont correlatie aan tussen microscopische structuren en macroscopische eigenschappen

Nieuwe studie toont correlatie aan tussen microscopische structuren en macroscopische eigenschappen Afbeelding:Tropische storm Khanun (Zuid-Chinese Zee)

Afbeelding:Tropische storm Khanun (Zuid-Chinese Zee)

- Elektronica

- Biologie

- Zonsverduistering

- Wiskunde

- French | Italian | Spanish | Portuguese | Swedish | German | Dutch | Danish | Norway |

-

Wetenschap © https://nl.scienceaq.com