Wetenschap

Zorgen over de verspreiding van microben op aarde mogen de zoektocht naar leven op Mars niet vertragen

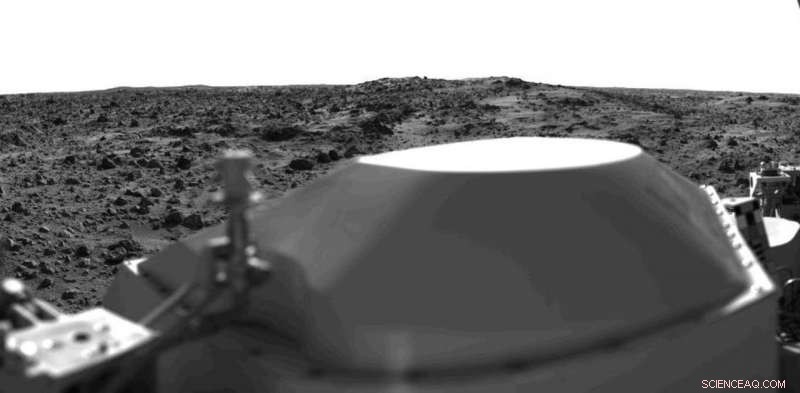

De Viking-landers waren in de jaren zeventig de laatste die rechtstreeks naar leven op Mars zochten. Krediet:NASA/JPL, CC BY

Er is misschien geen grotere vraag dan of we alleen zijn in ons zonnestelsel. Terwijl ons ruimtevaartuig nieuwe aanwijzingen vindt over de aanwezigheid van vloeibaar water nu of in het verleden op Mars, de mogelijkheid van een soort leven daar lijkt waarschijnlijker. Op aarde, water betekent leven, en daarom wordt de verkenning van Mars geleid door het idee om het water te volgen.

Maar de zoektocht naar leven op Mars gaat gepaard met tal van krachtige waarschuwingen over hoe we ons ruimtevaartuig moeten steriliseren om besmetting van onze buurplaneet te voorkomen. Hoe zullen we weten wat de inheemse Mars is als we de plaats onbedoeld bezaaien met aardse organismen? Een populaire analogie wijst erop dat Europeanen zonder het te weten pokken naar de Nieuwe Wereld brachten, en ze namen syfilis mee naar huis. evenzo, er wordt betoogd, onze robotverkenningen zouden Mars kunnen besmetten met terrestrische micro-organismen.

Als astrobioloog die de omgevingen van het vroege Mars onderzoekt, Ik stel voor dat deze argumenten misleidend zijn. Het huidige besmettingsgevaar via onbemande robots is eigenlijk vrij laag. Maar besmetting zal onvermijdelijk worden als astronauten daar eenmaal zijn. nasa, andere instanties en de particuliere sector hopen in de jaren 2030 menselijke missies naar Mars te sturen.

Ruimtevaartorganisaties hebben lang prioriteit gegeven aan het voorkomen van besmetting boven onze jacht op leven op Mars. Dit is het moment om deze strategie opnieuw te beoordelen en bij te werken - voordat mensen daar komen en onvermijdelijk aardse organismen introduceren, ondanks onze inspanningen.

Wat planetaire beschermingsprotocollen doen?

Argumenten die pleiten voor extra voorzichtigheid zijn doorgedrongen tot de verkenningsstrategieën van Mars en hebben geleid tot het creëren van specifiek leidend beleid, bekend als planetaire beschermingsprotocollen.

Er zijn strikte reinigingsprocedures vereist op ons ruimtevaartuig voordat ze gebieden op Mars mogen bemonsteren die een habitat kunnen zijn voor micro-organismen. ofwel inheems op Mars of daar vanaf de aarde gebracht. Deze gebieden worden door de bureaus voor planetaire bescherming bestempeld als 'Speciale Regio's'.

Microbiologen verzamelen vaak wattenstaafjes van de vloer van cleanrooms tijdens de montage van ruimtevaartuigen. Krediet:NASA/JPL-Caltech, CC BY

De zorg is dat, anders, terrestrische indringers kunnen potentieel leven op Mars in gevaar brengen. Ze zouden ook toekomstige onderzoekers kunnen verwarren die proberen onderscheid te maken tussen inheemse levensvormen op Mars en leven dat via het huidige ruimtevaartuig als besmetting van de aarde is aangekomen.

Het trieste gevolg van dit beleid is dat de miljarden dollars kostende Mars-ruimtevaartuigprogramma's van ruimteagentschappen in het Westen sinds het einde van de jaren zeventig niet proactief naar leven op de planeet hebben gezocht.

Toen deden de Viking-landers van NASA de enige poging ooit om leven op Mars te vinden (of op een andere planeet buiten de aarde, wat dat betreft). Ze voerden specifieke biologische experimenten uit op zoek naar bewijs van microbieel leven. Vanaf dat moment, dat beginnende biologische verkenning is verschoven naar minder ambitieuze geologische onderzoeken die alleen proberen aan te tonen dat Mars in het verleden "bewoonbaar" was, wat betekent dat het omstandigheden had die waarschijnlijk het leven zouden kunnen ondersteunen.

Nog erger, als een toegewijd, levenzoekend ruimtevaartuig ooit op Mars komt, planetair beschermingsbeleid zal het mogelijk maken om overal op het oppervlak van Mars naar leven te zoeken, behalve op de plaatsen waarvan we vermoeden dat er leven bestaat:de speciale regio's. De zorg is dat exploratie ze zou kunnen besmetten met terrestrische micro-organismen.

Kan het leven op aarde op Mars komen?

Denk nog eens aan de Europeanen die voor het eerst naar de Nieuwe Wereld reisden en terug. Ja, pokken en syfilis reisden met hen mee, tussen menselijke populaties, leven in warme lichamen op gematigde streken. Maar die situatie is niet relevant voor de verkenning van Mars. Elke analogie die betrekking heeft op mogelijke biologische uitwisseling tussen aarde en Mars, moet rekening houden met het absolute contrast in de omgeving van de planeten.

Een meer accurate analogie zou zijn om 12 Aziatische tropische papegaaien naar het Venezolaanse regenwoud te brengen. Over 10 jaar hebben we zeer waarschijnlijk een invasie van Aziatische papegaaien in Zuid-Amerika. Maar als we dezelfde 12 Aziatische papegaaien naar Antarctica brengen, over 10 uur hebben we 12 dode papegaaien.

Dr. Carl Sagan poseert met een model van de Viking-lander in Death Valley, Californië. Krediet:NASA, CC BY

We zouden aannemen dat elk inheems leven op Mars veel beter zou moeten zijn aangepast aan de stress van Mars dan het leven op aarde, en zou daarom alle mogelijke nieuwkomers op het land overtreffen. Micro-organismen op aarde zijn geëvolueerd om te gedijen in uitdagende omgevingen zoals zoutkorsten in de Atacama-woestijn of hydrothermale bronnen op de diepe oceaanbodem. In the same way, we can imagine any potential Martian biosphere would have experienced enormous evolutionary pressure during billions of years to become expert in inhabiting Mars' today environments. The microorganisms hitchhiking on our spacecraft wouldn't stand much of a chance against super-specialized Martians in their own territory.

So if Earth life cannot survive and, het belangrijkste, reproduce on Mars, concerns going forward about our spacecraft contaminating Mars with terrestrial organisms are unwarranted. This would be the parrots-in-Antarctica scenario.

Anderzijds, perhaps Earth microorganisms can, in feite, survive and create active microbial ecosystems on present-day Mars – the parrots-in-South America scenario. We can then presume that terrestrial microorganisms are already there, carried by any one of the dozens of spacecraft sent from Earth in the last decades, or by the natural exchange of rocks pulled out from one planet by a meteoritic impact and transported to the other.

In dit geval, protection protocols are overly cautious since contamination is already a fact.

Technological reasons the protocols don't make sense

Another argument to soften planetary protection protocols hinges on the fact that current sterilization methods don't actually "sterilize" our spacecraft, a feat engineers still don't know how to accomplish definitively.

The cleaning procedures we use on our robots rely on pretty much the same stresses prevailing on the Martian surface:oxidizing chemicals and radiation. They end up killing only those microorganisms with no chance of surviving on Mars anyway. So current cleaning protocols are essentially conducting an artificial selection experiment, with the result that we carry to Mars only the most hardy microorganisms. This should put into question the whole cleaning procedure.

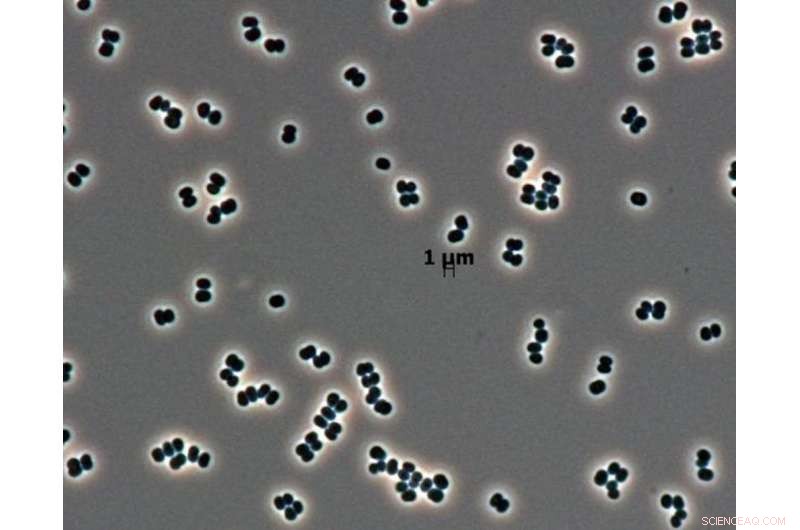

Bacterial species Tersicoccus phoenicis is found in only two places:clean rooms in Florida and South America where spacecraft are assembled for launch. Credit:NASA/JPL-Caltech, CC BY

Verder, technology has advanced enough that distinguishing between Earthlings and Martians is no longer a problem. If Martian life is biochemically similar to Earth life, we could sequence genomes of any organisms located. If they don't match anything we know is on Earth, we can surmise it's native to Mars. Then we could add Mars' creatures to the tree of DNA-based life we already know, probably somewhere on its lower branches. And if it is different, we would be able to identify such differences based on its building blocks.

Mars explorers have yet another technique to help differentiate between Earth and Mars life. The microbes we know persist in clean spacecraft assembly rooms provide an excellent control with which to monitor potential contamination. Any microorganism found in a Martian sample identical or highly similar to those present in the clean rooms would very likely indicate contamination – not indigenous life on Mars.

The window is closing

On top of all these reasons, it's pointless to split hairs about current planetary protection guidelines as applied to today's unmanned robots since human explorers are on the horizon. People would inevitably bring microbial hitchhikers with them, because we cannot sterilize humans. Contamination risks between robotic and manned missions are simply not comparable.

Whether the microbes that fly with humans will be able to last on Mars is a separate question – though their survival is probably assured if they stay within a spacesuit or a human habitat engineered to preserve life. But no matter what, they'll definitely be introduced to the Martian environment. Continuing to delay the astrobiological exploration of Mars now because we don't want to contaminate the planet with microorganisms hiding in our spacecrafts isn't logical considering astronauts (and their microbial stowaways) may arrive within two or three decades.

Prior to landing humans on Mars or bringing samples back to Earth, it makes sense to determine whether there is indigenous Martian life. What might robots or astronauts encounter there – and import to Earth? More knowledge now will increase the safety of Earth's biosphere. Ten slotte, we still don't know if returning samples could endanger humanity and the terrestrial biosphere. Perhaps reverse contamination should be our big concern.

The main goal of Mars exploration should be to try to find life on Mars and address the question of whether it is a separate genesis or shares a common ancestor with life on Earth. Uiteindelijk, if Mars is lifeless, maybe we are alone in the universe; but if there is or was life on Mars, then there's a zoo out there.

Dit artikel is oorspronkelijk gepubliceerd op The Conversation. Lees het originele artikel.

Hoe de PKA te berekenen in titratie

Hoe de PKA te berekenen in titratie  Wetenschappers ontwikkelen duurzame manier om chitine uit garnalenschelpen te extraheren door het te vergisten met fruitafval

Wetenschappers ontwikkelen duurzame manier om chitine uit garnalenschelpen te extraheren door het te vergisten met fruitafval Tijdmachine biedt nieuwe aanpak voor het testen van geneesmiddelen voor alvleesklierkanker

Tijdmachine biedt nieuwe aanpak voor het testen van geneesmiddelen voor alvleesklierkanker Op klei gebaseerde antimicrobiële verpakking houdt voedsel vers

Op klei gebaseerde antimicrobiële verpakking houdt voedsel vers Hoe bereken ik de stijging van de temperatuur?

Hoe bereken ik de stijging van de temperatuur?

Bewijs voor aanhoudende afhankelijkheid van bossen door inheemse volkeren in het historische Sri Lanka

Bewijs voor aanhoudende afhankelijkheid van bossen door inheemse volkeren in het historische Sri Lanka Onderzoek bevestigt de timing van het smelten van tropische gletsjers aan het einde van de laatste ijstijd

Onderzoek bevestigt de timing van het smelten van tropische gletsjers aan het einde van de laatste ijstijd De plastic mythe en de onbegrepen driehoek

De plastic mythe en de onbegrepen driehoek Californische oliepijpleiding had een jaar kunnen lekken:onderzoekers

Californische oliepijpleiding had een jaar kunnen lekken:onderzoekers Hydraulisch breken zelden gekoppeld aan gevoelde seismische trillingen:studie

Hydraulisch breken zelden gekoppeld aan gevoelde seismische trillingen:studie

Hoofdlijnen

- Rangorde gebruiken om complexe genetische interacties te identificeren

- Biologische klok gevonden in schimmelparasiet werpt meer licht op het fenomeen zombiemieren

- Biologen kijken naar het verleden voor vroege genetische ontwikkeling van kleine spinnen- en insectenogen

- Zijn linkshandigen snellere denkers dan rechtshandigen?

- Is het waar dat als je drie weken iets doet, het een gewoonte wordt?

- Een sleutel vinden om geblokkeerde differentiatie in microRNA-deficiënte embryonale stamcellen te ontgrendelen

- Moleculaire genetica (biologie): een overzicht

- Voor een gestreepte mangoest in het noorden van Botswana, communiceren met familie kan dodelijk zijn

- Lovelorn koala gepakt na ontsnapping uit dierentuin op jacht naar partner

- Wetenschappers ontdekken pulserende overblijfselen van een ster in een verduisterend dubbelstersysteem

- Nieuwe energetische pulsar ontdekt in de Kleine Magelhaense Wolk

- Bemanning niet in gevaar nadat ISS-problemen zijn opgelost:Rusland

- NASA-ruimtevaartuig maakt een foto van Jupiter ... vanaf de maan

- Tientallen nieuwe ultradiffuse sterrenstelsels ontdekt in Abell 2744

Hoe een T-statistiek berekenen

Hoe een T-statistiek berekenen  Touwtrekken rond de zwaartekracht

Touwtrekken rond de zwaartekracht Drie kenmerken van de perfecte vlam op een bunsenbrander

Drie kenmerken van de perfecte vlam op een bunsenbrander  2D-eilanden in grafeen zijn veelbelovend voor toekomstige fabricage van apparaten

2D-eilanden in grafeen zijn veelbelovend voor toekomstige fabricage van apparaten Bloed en zweet:draagbare medische sensoren krijgen een grote gevoeligheidsboost

Bloed en zweet:draagbare medische sensoren krijgen een grote gevoeligheidsboost Hoe ziet een door vrouwen gerunde samenleving eruit?

Hoe ziet een door vrouwen gerunde samenleving eruit?  Afbeelding:Momentopname van kosmische pyrotechniek

Afbeelding:Momentopname van kosmische pyrotechniek Een galactisch juweel:FORS2-instrument legt verbluffende details vast van spiraalstelsel NGC 3981

Een galactisch juweel:FORS2-instrument legt verbluffende details vast van spiraalstelsel NGC 3981

- Elektronica

- Biologie

- Zonsverduistering

- Wiskunde

- French | Italian | Spanish | Portuguese | Swedish | German | Dutch | Danish | Norway |

-

Wetenschap © https://nl.scienceaq.com