Wetenschap

Handschriftexaminatoren in het digitale tijdperk

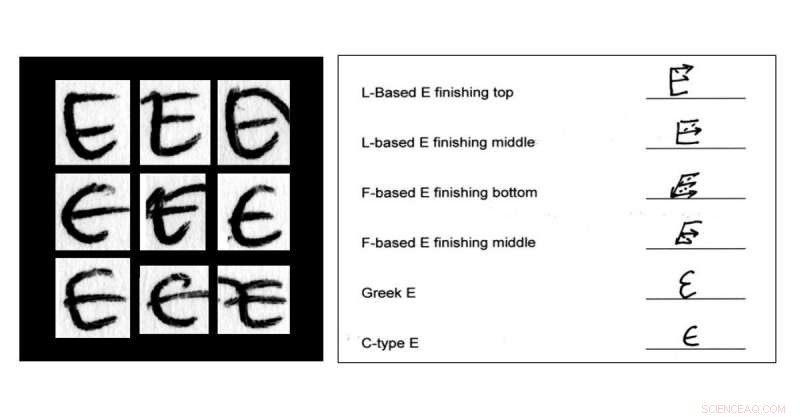

Een reeks natuurlijke variaties in de hoofdletter 'E' van één schrijver. Krediet:NIST

Mensen schrijven meer dan ooit met hun toetsenborden en telefoons, maar handgeschreven notities zijn zeldzaam geworden. Zelfs handtekeningen raken uit de mode. Voor de meeste creditcardaankopen zijn ze niet langer nodig, en als ze dat doen, je kunt er meestal gewoon een uitkrabben met je vingernagel. De eeuwenoude kunst van het handschrift is in verval.

Dit markeert een diepgaande verschuiving in de manier waarop we communiceren, maar voor een groep experts roept het ook een existentiële vraag op. Forensische handschriftonderzoekers verifiëren handgeschreven notities en handtekeningen - of onthullen ze als vervalsingen - door onderscheidende kenmerken in ons schrijven te analyseren. Omdat mensen minder met de hand schrijven, wordt handschriftonderzoek irrelevant?

Een recent rapport van het National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) suggereert dat het antwoord nee is - als het veld verandert om bij de tijd te blijven. Maar de tijden veranderen in meer dan één opzicht, en de afname van het handschrift is slechts een van de uitdagingen waarmee het vakgebied rekening zal moeten houden.

Hoe de experts het doen

Emily Will is een gecertificeerde handschriftexaminator in een privépraktijk in North Carolina. Ze heeft handtekeningen op talloze cheques onderzocht, testamenten, daden en trusts. Zij heeft medisch dossier ingezien om te beoordelen of de handtekening van een arts mogelijk op een later tijdstip dan aangegeven is geplaatst, misschien nadat er een rechtszaak was aangespannen. Ze heeft ook langere vormen van schrijven onderzocht, zoals dreigende of intimiderende brieven en zelfmoordbriefjes. Als het schijnbare zelfmoordslachtoffer het briefje niet heeft geschreven, de politie kan een moord op hun handen hebben.

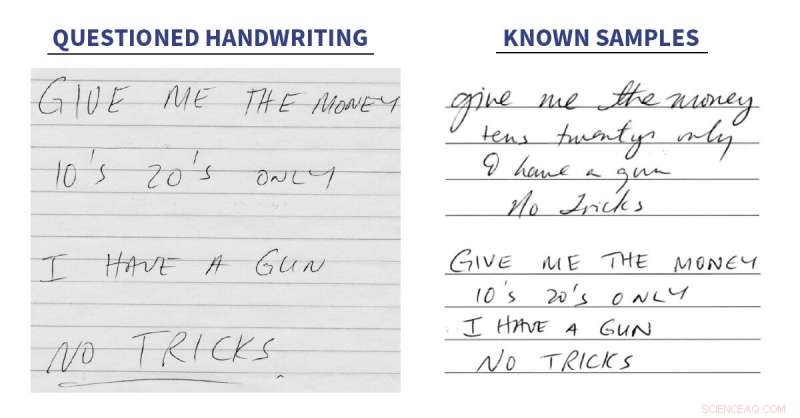

Om te beoordelen of een handschrift door een bepaalde persoon is geschreven, examinatoren hebben iets nodig om het mee te vergelijken, dus verzamelen ze schrijfvoorbeelden waarvan bekend is dat ze van die persoon afkomstig zijn. Het type schrift moet hetzelfde zijn, of een handtekening, schuinschrift, of met de hand afdrukken. De bekende voorbeelden moeten uit ongeveer dezelfde tijdsperiode komen als het betreffende handschrift, omdat ons handschrift in de loop van de tijd evolueert. En het is essentieel om meerdere bekende voorbeelden te hebben om mee te vergelijken, omdat de examinator dan rekening kan houden met de variabiliteit in iemands schrijfstijl.

"Je bent geen robot, dus elke keer dat je je naam tekent, het zal er anders uitzien, ' zei Will. 'Dat maakt handschriftonderzoek zo interessant.'

Niet-professionals denken misschien dat, aangezien de meeste mensen weten hoe ze handschrift moeten maken, vrijwel iedereen kan het onderzoeken. Ze zouden kunnen aannemen dat de deskundige zaken vergelijkt als de grootte, helling en afstand van de letters en de verbindingen daartussen. Inderdaad, examinatoren doen dat. Maar ze kijken ook verder dan die kenmerken van schrijven voor subtielere tekenen van hoe het schrijven is gemaakt.

"Stel dat je een handtekening wilt vervalsen, ' zei Will. 'Misschien kun je een goede facsimile maken. Maar is de "O' met de klok mee wanneer het tegen de klok in zou moeten zijn? Zijn er penliften waar dat niet zou moeten zijn? Als je je naam tekent, is het allemaal spiergeheugen. Maar een handtekening smeden vereist overleg. De pen vertraagt. Hij stopt en begint ." Die aarzelingen verschijnen onder een microscoop als kleine plasjes inkt.

"Het gaat er niet zozeer om hoe de handtekening eruitziet, maar hoe het werd uitgevoerd dat is belangrijk, ' zei Wil.

Dit is wat Will in haar tas meeneemt:een juweliersloep, een kleine optische microscoop en een draagbare digitale microscoop. Een zaklamp. Een papiermicrometer, om de dikte van papier te meten. Een laptop en draagbare scanner. Een camera die aansluit op haar microscopen. "En eerlijk gezegd " ze zegt, "Ik gebruik mijn iPhone tegenwoordig veel."

De praktijk van Will strekt zich uit tot het bredere veld van "onderzoek van twijfelachtige documenten, " wat inhoudt dat een heel document wordt onderzocht op tekenen van fraude. In haar lab, ze heeft apparatuur om papier en inkt te analyseren en onder verschillende soorten licht te bekijken. Sommige inkten die er bij daglicht identiek uitzien, zien er onder infrarood heel anders uit. Ze identificeert uitwissingen, wijzigingen en vernietigingen en onthult ingesprongen schrift - de indrukken achtergelaten op vellen papier onder de geschreven notitie.

Maar het meeste van Wills werk omvat handschrift en handtekeningen, en dat zijn er tegenwoordig veel minder. Fraude met het verzilveren van cheques is ver weg nu loonstrookjes en socialezekerheidscheques direct worden gestort. Medical malpractice lawsuits involve fewer signatures since electronic health records have become the norm. Even celebrities have noticed the change. In a 2014 opinion article in The Wall Street Journal, Taylor Swift wrote, "I haven't been asked for an autograph since the invention of the iPhone with a front-facing camera."

Enough handwriting still passes under Will's microscope to keep her in business. Maar, ze zegt, "If I were a young person starting out today, I might consider cybersecurity."

Forensic handwriting examiners can only compare writing of the same type. In dit geval, only the second known sample can be compared to the questioned handwriting. Credit:NIST

A Roadmap for Staying Relevant

The field of forensic handwriting examination may have trouble attracting new blood. A report from NIST earlier this year found that the median age for handwriting examiners is 60, compared with 42 to 44 for people in similar scientific and technical occupations. That report, Forensic Handwriting Examination and Human Factors:Improving the Practice Through a Systems Approach, was published by NIST, but was written by 23 outside experts, including Will.

To increase recruitment, the report recommends replacing the unpaid apprenticeships that have been the traditional route of entry into the field with grants and fellowships. The report also recommends cross-training with other forensic disciplines that involve pattern matching, such as fingerprint examination.

The "human factors" in the report's title refers to a field of study that seeks to understand the factors that affect human capability and job performance. In forensic science, these include training, communicatie, technology and management policies, to name just a few.

Melissa Taylor, the NIST human factors expert who led the group of authors, said that the report provides the forensic handwriting community with a road map for staying relevant. But the threat of irrelevance doesn't come only from the decline in handwriting. Part of the challenge, ze zegt, arises from the field of forensic science itself.

"There is a big push toward greater reliability and more rigorous research in forensic science, " zei Taylor, whose research is aimed at reducing errors and improving job performance in handwriting examination and other forensic disciplines, including fingerprints and DNA. "To stay relevant, the field of handwriting examination will have to change with the times."

Among other changes, the report recommends more research to estimate error rates for the field. This will allow juries and others to consider the potential for error when weighing an examiner's testimony. The report also recommends that experts avoid testifying in absolute terms or saying that an individual has written something to the exclusion of all other writers. In plaats daarvan, experts should report their findings in terms of relative probabilities and degrees of certainty.

These recommendations are consistent with findings in a landmark 2009 report from the National Academy of Sciences. Called Strengthening Forensic Science in the United States:A Path Forward, that report said that "there may be a scientific basis for handwriting comparison, " but that there has been only limited research on its reliability.

Knowing When to Not Make a Call

Children used to learn handwriting in school by copying letters and phrases from books that contained models of ideal penmanship. Different copybooks had different styles, and an expert could often tell from a person's handwriting whether they were trained in the Palmer style, the Spencer style, or something else. By identifying a specific copybook style, an examiner could quickly narrow the range of potential writers.

Many children no longer learn cursive writing in school, and whether this helps or hinders handwriting examination is unknown. "It might actually make handwriting more identifiable because it allows people to develop their own individual styles of writing, " said Linton Mohammed, author of the widely used textbook Forensic Examination of Signatures, and a co-author of the NIST-led study.

Anderzijds, it might make the task harder by depriving experts of a system for classifying writing styles. This is one reason why research on error rates is needed. The way people learn to write has changed, and error-rate studies can show whether handwriting examiners are successfully adapting to those changes. "We claim to be good at this, " Mohammed said. "But how good are we really?"

Several studies have attempted to answer this question by testing whether experts are more competent at handwriting examination than people with no training. The results reveal a great deal about both handwriting examination and human psychology.

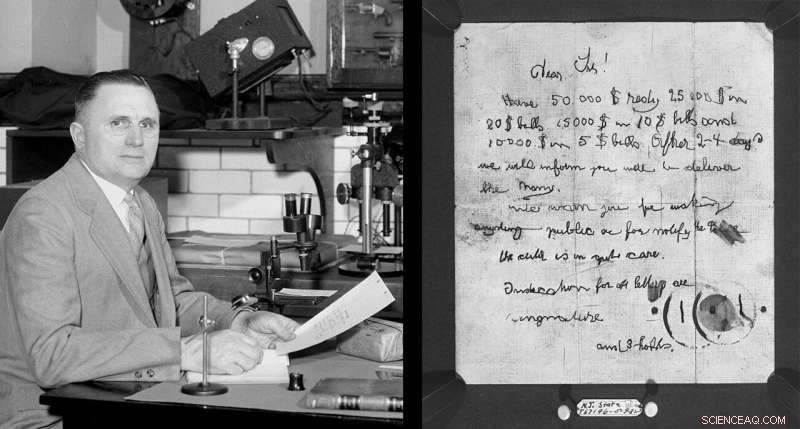

In the 1930s, a physicist at NIST, then known as the National Bureau of Standards, became a leading handwriting expert. His name was Wilmer Souder, and the most famous case he worked on was 1932 the kidnapping of Charles Lindberg Jr., the infant son of the famous aviator. Despite the notoriety of this case, Souder himself kept an extremely low profile — so much so that when he retired, a profile in "Reader's Digest" referred to him as Detective X. Credit:NBS/NIST; source:NARA

In many of these studies, participants are shown pairs of signatures and asked to determine whether they are both by the same person or if one is a fake. Calculating overall error rates from multiple studies is difficult due to differences in study design. But consistently, across studies, both experts and novices made roughly the same proportion of correct decisions, according to a 2018 metastudy led by Alice Towler at the University of New South Wales, Australia. The novices, echter, made a much higher proportion of errors, while the experts more frequently declined to make a call. If a signature lacked complexity or was otherwise difficult to compare, the experts would more readily find the evidence inconclusive. This ability to defer judgment is critical to reducing errors in forensic science.

The tendency of novices to rush to judgment in cases where experts defer reflects a quirk of human psychology. People with limited knowledge or expertise in a subject often overestimate their own competence. This is called the Dunning-Kruger effect, for the psychologists who first described it. In the case of handwriting, people might be particularly susceptible. After all, pretty much anyone can produce handwriting. How hard can it be to examine?

But error rate studies show that at least some experts recognize their limitations when faced with a difficult task. "I've been doing this for 30-plus years, and I realized early on that there's a lot that we don't know, " Mohammed said. "So we have to be very careful in reaching our conclusions."

The End of Handwriting Examination, or a New Beginning?

Like Emily Will, Mohammed has examined many wills, deeds and trusts. He has also analyzed ransom notes, threatening letters, and one hit list. Being based in the San Francisco Bay Area, where the tech boom has minted many fortunes, he has also examined many stock-option grants and prenuptial agreements.

Although Mohammed started his career with the San Diego County Sheriff's Department, today he is in private practice. In his current home base of northern California, hij zegt, there are no government laboratories that still examine questioned documents. This reflects a nationwide trend—a report from the Department of Justice found that only 14% of publicly funded crime labs did their own questioned document examinations in 2014, down from 24% in 2002.

Those numbers may mean that the field is consolidating rather than disappearing. If smaller labs can no longer support in-house experts due to a diminishing caseload, they can farm out work to private sector experts like Will and Mohammed. Tegelijkertijd, larger federal labs, including the FBI Laboratory and the U.S. Army's Defense Forensic Science Center, continue to maintain questioned document units. This is in part because their focus includes international terrorism, where handwritten documents are still a source of valuable intelligence, and in part because the United States is a big place. Nationwide, crimes involving handwriting still occur frequently enough that federal labs need to keep experts on staff.

When asked if handwriting examiners will soon become irrelevant, one federal expert said that as long as greed and fraud exist, there will be a need for handwriting examiners.

When asked the same question, Mohammed noted that changing technology did not doom the field in the past. "When the ballpoint pen came out, people said, "That's the end of handwriting examination, '" he said. People mostly stopped using fountain pens, but handwriting examination survived the transition.

Melissa Taylor, the NIST expert, agrees that handwriting examination is still a needed skill and will remain relevant—if the field successfully adapts to changing expectations around research and reliability. And if the new report, which counts many leading handwriting experts among its authors, is any indication, the needed changes may already be underway.

"There will still be documents. There will still be signatures, " Taylor said. "And most people don't print stickup notes on their laser printer. They scribble them on the dashboard before running into the bank."

Some things will never change.

Voedselzekerheid:bestraling en etherische oliedampen voor de behandeling van granen

Voedselzekerheid:bestraling en etherische oliedampen voor de behandeling van granen Eenvoudige test kan fluoridegerelateerde ziekte voorkomen

Eenvoudige test kan fluoridegerelateerde ziekte voorkomen Video:Betere pannenkoeken door chemie

Video:Betere pannenkoeken door chemie Nieuwe elektronenbril verscherpt onze kijk op kenmerken op atomaire schaal

Nieuwe elektronenbril verscherpt onze kijk op kenmerken op atomaire schaal Polymeer dat geneest als een huid, zeer dicht bij productie op industriële schaal

Polymeer dat geneest als een huid, zeer dicht bij productie op industriële schaal

Indonesië verhoogt alarmniveau voor vulkaan Bali

Indonesië verhoogt alarmniveau voor vulkaan Bali Het is tijd dat milieuactivisten spraken over het bevolkingsprobleem

Het is tijd dat milieuactivisten spraken over het bevolkingsprobleem Siciliaans dorp ruimt as op, stenen van de uitbarsting van de Etna

Siciliaans dorp ruimt as op, stenen van de uitbarsting van de Etna Overstromingsrisico's:Nauwkeurigere gegevens door COVID-19

Overstromingsrisico's:Nauwkeurigere gegevens door COVID-19 Het prehistorische verleden verbinden met de wereldwijde toekomst

Het prehistorische verleden verbinden met de wereldwijde toekomst

Hoofdlijnen

- Europa zet $ 1,18 miljard in om het leven in zee beter te beschermen

- Your Brain On: Empathy

- Top 5 manieren om slimmer te worden

- Wat is het principe van parsimony in de biologie?

- Knoflook kan chronische infecties bestrijden

- Hoe regelt het lichaam de hartslag?

- Kevers felle kleuren gebruikt voor camouflage in plaats van roofdieren te waarschuwen

- Epigenetica legt uit waarom je DNA je lot niet voorspelt

- Een gemakkelijke manier om de schedelzenuwen te leren

- Onderzoeker onderzoekt waarom kaarten viraal gaan op internet

- De voordelen van een asteroïde bombarderen

- 10 Afro-Amerikanen genaamd Rhodes-geleerden, meest ooit

- Staten schorten gestandaardiseerde tests op nu scholen sluiten

- Zet pay-to-play sport, buitenschoolse activiteiten die voor sommige studenten buiten bereik zijn?

Fabricage van krachtige telescoop begint

Fabricage van krachtige telescoop begint Onderzoek test welk nanosysteem het beste werkt bij kankerbehandeling

Onderzoek test welk nanosysteem het beste werkt bij kankerbehandeling Studie identificeert het belang van atmosferische rivieren voor Nieuw-Zeeland

Studie identificeert het belang van atmosferische rivieren voor Nieuw-Zeeland EU-orgaan:klimaatverandering brengt steeds grotere risico's met zich mee

EU-orgaan:klimaatverandering brengt steeds grotere risico's met zich mee Milieuvriendelijke vlamvertrager kan worden afgebroken tot minder veilige verbindingen

Milieuvriendelijke vlamvertrager kan worden afgebroken tot minder veilige verbindingen New York neemt het verkeer serieus met het eerste stadsbrede tariefplan voor congestie in de VS

New York neemt het verkeer serieus met het eerste stadsbrede tariefplan voor congestie in de VS Uitgebreide elektronische structuurmethoden voor materiaalontwerp

Uitgebreide elektronische structuurmethoden voor materiaalontwerp Klimaatverandering heeft een storm van onzekerheid veroorzaakt. Deze onderzoekers hebben er zin in.

Klimaatverandering heeft een storm van onzekerheid veroorzaakt. Deze onderzoekers hebben er zin in.

- Elektronica

- Biologie

- Zonsverduistering

- Wiskunde

- French | Italian | Spanish | Portuguese | Swedish | German | Dutch | Danish | Norway |

-

Wetenschap © https://nl.scienceaq.com