Wetenschap

Hoe röntgenstralen betere batterijen kunnen maken

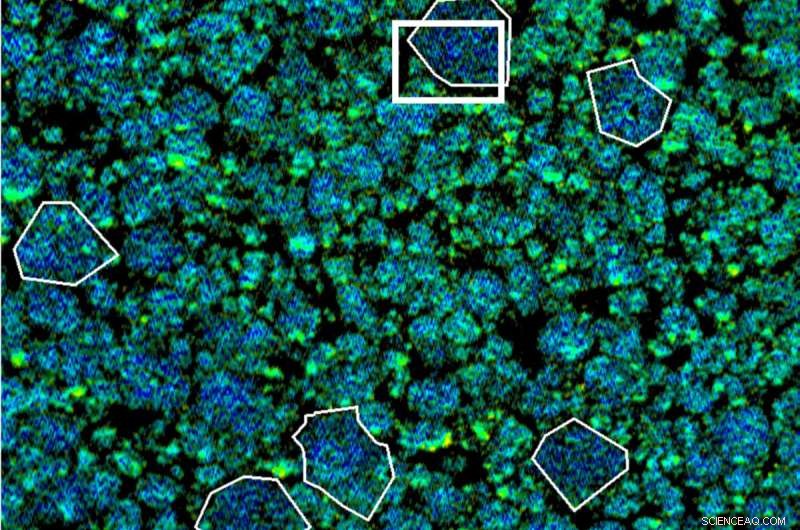

Gedetailleerde röntgenmetingen bij de Advanced Light Source hielpen een onderzoeksteam onder leiding van Berkeley Lab, SLAC en Stanford University om te onthullen hoe zuurstof sijpelt uit de miljarden nanodeeltjes waaruit lithium-ionbatterij-elektroden bestaan. Krediet:Berkeley Lab

Over een periode van drie maanden produceert de gemiddelde auto in de VS één ton koolstofdioxide. Vermenigvuldig dat met alle benzineauto's op aarde, en hoe ziet dat eruit? Een onoverkomelijk probleem.

Maar nieuwe onderzoeksinspanningen zeggen dat er hoop is als we ons inzetten voor een netto-nul CO2-uitstoot tegen 2050, en gasverslindende voertuigen vervangen door elektrische voertuigen, naast vele andere oplossingen voor schone energie.

Om onze natie te helpen dit doel te bereiken, werken wetenschappers zoals William Chueh en David Shapiro samen om nieuwe strategieën te bedenken om veiligere langeafstandsbatterijen te ontwerpen die zijn gemaakt van duurzame, aardrijke materialen.

Chueh is universitair hoofddocent materiaalwetenschap en -techniek aan de Stanford University met als doel de moderne batterij van onderaf opnieuw te ontwerpen. Hij vertrouwt op ultramoderne hulpmiddelen van wetenschappelijke gebruikersfaciliteiten van het Amerikaanse Department of Energy, zoals Berkeley Lab's Advanced Light Source (ALS) en SLAC's Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Light Source - synchrotronfaciliteiten die heldere bundels röntgenlicht genereren - om te onthullen de moleculaire dynamica van batterijmaterialen aan het werk.

Al bijna tien jaar werkt Chueh samen met Shapiro, een senior stafwetenschapper bij de ALS en een toonaangevende synchrotron-expert - en samen heeft hun werk geresulteerd in verbluffende nieuwe technieken die voor het eerst onthullen hoe batterijmaterialen in actie werken, in realtime , op ongekende schaal onzichtbaar voor het blote oog.

In deze Q&A bespreken ze hun pionierswerk.

V:Waardoor ben je geïnteresseerd geraakt in onderzoek naar batterij-/energieopslag?

Chueh:Mijn werk wordt bijna volledig gedreven door duurzaamheid. Ik raakte betrokken bij onderzoek naar energiematerialen toen ik begin jaren 2000 afstudeerde - ik werkte aan brandstofceltechnologie. Toen ik in 2012 bij Stanford kwam werken, werd het me duidelijk dat schaalbare en efficiënte energieopslag cruciaal is.

Vandaag de dag ben ik erg enthousiast om te zien dat de energietransitie weg van fossiele brandstoffen nu realiteit wordt en dat deze op ongelooflijke schaal wordt geïmplementeerd.

Ik heb drie doelen:Ten eerste doe ik fundamenteel onderzoek dat de basis legt om de energietransitie mogelijk te maken, met name op het gebied van materiaalontwikkeling. Ten tweede train ik wetenschappers en ingenieurs van wereldklasse die de echte wereld in gaan om deze problemen op te lossen. En ten derde neem ik de fundamentele wetenschap en vertaal ik deze naar praktisch gebruik door middel van ondernemerschap en technologieoverdracht.

Dus hopelijk geeft dat je een uitgebreid beeld van wat mij drijft en wat ik denk dat er nodig is om een verschil te maken:het zijn de kennis, de mensen en de technologie.

Shapiro:Mijn achtergrond ligt in optica en coherente röntgenverstrooiing, dus toen ik in 2012 voor het eerst bij de ALS begon te werken, stonden batterijen niet echt op mijn radar. Ik kreeg de taak om nieuwe technologieën te ontwikkelen voor röntgenmicroscopie met hoge ruimtelijke resolutie, maar dit leidde al snel tot de toepassingen en het proberen te achterhalen wat onderzoekers van Berkeley Lab en daarbuiten doen en wat hun behoeften zijn.

Destijds, rond 2013, was er veel werk aan de ALS met behulp van verschillende technieken die gebruikmaken van de chemische gevoeligheid van zachte röntgenstralen om fasetransformaties in batterijmaterialen te bestuderen, met name lithiumijzerfosfaat (LiFePO4) in het bijzonder.

Ik was erg onder de indruk van Wills werk, maar ook van Wanli Yang, Jordi Cabana (een voormalig stafwetenschapper in Berkeley Lab's Energy Technologies Area (ETA) die nu universitair hoofddocent is aan de University of Illinois Chicago), en anderen wiens werk ook werk van ETA-onderzoekers Robert Kostecki en Marca Doeff.

I knew nothing about batteries at the time, but the scientific and social impact of this area of research quickly became apparent to me. The synergy of research across Berkeley Lab also struck me as very profound, and I wanted to figure out how to contribute to that. So I started to reach out to people to see what we could do together.

As it turned out, there was a great need to improve the spatial resolution of our battery materials measurements and to look at them during cycling—and Will and I have been working on that for nearly a decade now.

Q:Will, as a battery scientist, what would you say is the biggest challenge to making better batteries?

Chueh:Batteries have on the order of 10 metrics that you have to co-optimize at the same time. It's easy to make a battery that's good on maybe five out of the 10, but to make a battery that's good in every metric is very immensely challenging.

For example, let's say you want a battery that is energy dense so you can drive an electric car for 500 miles per charge. You may want a battery that charges in 10 minutes. And you may want a battery that lasts 20 years. You also want a battery that never explodes. But it's hard to meet all of these metrics at once.

What we're trying to do is understand how we can create a single battery technology that is safe, long-lasting, and can be charged in 10 minutes.

And those are the fundamental insights that our experiments at Berkeley Lab's Advanced Light Source are trying to do:To uncover those unexplained tradeoffs so that we can go beyond today's design rules, which would enable us to identify new materials and new mechanisms so that we can free ourselves from those restrictions.

Q:What unique capabilities does the ALS offer that have helped to push the boundaries of battery or energy storage research?

Chueh:In order to understand what's going on, we need to see it. We need to make observations. A key philosophy of my group is to embrace the dynamics and the heterogeneity of battery materials. A battery material is not like a rock. It's not static. You are charging and discharging it every day for your phones and every week for your electric cars. You're not going to understand how a car works by not driving it.

The second part is that heterogeneous battery materials are extremely length spanning. A battery cell is typically a few centimeters tall, but in order to understand what's going on inside the battery—and I have beautiful images for this—you want to see all the way down to the nanoscale and to the atomic scale. That's about 10 orders of magnitude of length.

What the Advanced Light Source empowers scientists like me to be able to do is to embrace the heterogeneity and dynamics of a battery in very unprecedented ways:We can measure very slow processes. We can measure very fast processes. We can measure things at the scale of many hundreds of microns (millionths of a meter). We can measure things at the nanoscale (billionth of a meter). All with one amazing tool at Berkeley Lab.

Shapiro:Scanning transmission X-ray microscopy (STXM) is a very popular synchrotron-based method. Most synchrotrons around the world have at least one STXM instrument while the ALS has three—and a fourth is on the way through the ALS Upgrade (ALS-U) project.

I think a few things make our program unique. First, we have a portfolio of instruments with specializations. One is optimized for light element spectroscopy so an element like oxygen, which is a critical ingredient in battery chemistry, can be precisely characterized.

Another instrument specializes in mapping chemical composition at very high spatial resolution. We have the highest spatial resolution X-ray microscopy in the world. This is very powerful for zooming in on the chemical reactions happening within a battery's individual nanoparticles and interfaces.

Our third instrument specializes in "operando" measurements of battery chemistry, which you need in order to really understand the physical and chemical evolution that occurs during battery cycling.

We have also worked hard to develop synergies with other facilities at Berkeley Lab. For instance, our high-resolution microscope uses the same sample environments as the electron microscopes at the Molecular Foundry, Berkeley Lab's nanoscience user facility—so it has become feasible to probe the same active battery environment with both X-rays and electrons. Will has used this correlative approach to study relationships between chemical states and structural strain in battery materials. This has never been done before at the length scales we have access to, and it provides new insight.

Q:How will the ALS Upgrade project advance next-gen energy storage technologies? What will the upgraded ALS offer battery/energy-storage researchers that will be unique to Berkeley Lab?

Shapiro:The upgraded ALS will be unique for a few reasons as far as microscopy is concerned. First, it will be the brightest soft X-ray source in the world, providing 100 times more X-rays on th sample than what we have today. Scanning microscopy techniques will benefit from such high brightness.

This is both a huge opportunity and a huge challenge. We can use this brightness to measure the data we get today—but doing this 100 times faster is the challenging part.

Such new capabilities will give us a much more statistically accurate look at battery structure and function by expanding to larger length scales and smaller time scales. Alternatively, we could also measure data at the same rate as today but with about three times finer spatial resolution, taking us from about 10 nanometers to just a few nanometers. This is a very important length scale for materials science, but today it's just not accessible by X-ray microscopy.

Another thing that will make the upgraded ALS unique is its proximity to expertise at the Molecular Foundry; other science areas such as the Energy Technologies Area; and current and future energy research hubs based at Berkeley Lab. This synergy will continue to drive energy storage research.

Chueh:In battery research, one of the challenges we have right now is that we have so many interesting problems to solve, but it takes hours and days to do just one measurement. The ALS-U project will increase the throughput of experiments and allow us to probe materials at higher resolution and smaller scales. Altogether, that adds up to enabling new science. Years ago, I contributed to making the case for ALS-U, so I couldn't be prouder to be part of that—I'm very excited to see the upgraded ALS come online so we can take advantage of its exciting new capabilities to do science that we cannot do today.

Een zilveren randje voor extreme elektronica

Een zilveren randje voor extreme elektronica Leraren maken Frankensteel tijdens Materials Camp bij MIT

Leraren maken Frankensteel tijdens Materials Camp bij MIT Bio-sensing contactlens kan op een dag bloedglucose meten, andere lichaamsfuncties

Bio-sensing contactlens kan op een dag bloedglucose meten, andere lichaamsfuncties Nieuwe katalysator kan betere lithium-zwavelbatterijen mogelijk maken, voeding van de volgende generatie elektronica

Nieuwe katalysator kan betere lithium-zwavelbatterijen mogelijk maken, voeding van de volgende generatie elektronica Het aantal neutronen, protonen en elektronen voor atomen, ionen en isotopen vinden

Het aantal neutronen, protonen en elektronen voor atomen, ionen en isotopen vinden

NASA ziet tropische cycloon Joaninha Mauritius treffen

NASA ziet tropische cycloon Joaninha Mauritius treffen Rode Zee-provincie Egypte gaat plastic voor eenmalig gebruik verbieden

Rode Zee-provincie Egypte gaat plastic voor eenmalig gebruik verbieden Grote wind- en zonneparken in de Sahara zouden de warmte verhogen, regenen, vegetatie

Grote wind- en zonneparken in de Sahara zouden de warmte verhogen, regenen, vegetatie Uit onderzoek blijkt dat de kooldioxide-emissies van de Amazone rivier de opname op het land bijna in evenwicht houden

Uit onderzoek blijkt dat de kooldioxide-emissies van de Amazone rivier de opname op het land bijna in evenwicht houden Hoe een Nederlandse man die zwerfvuil verzamelde in een wetenschappelijk artikel belandde

Hoe een Nederlandse man die zwerfvuil verzamelde in een wetenschappelijk artikel belandde

Hoofdlijnen

- Hoe evolueren bacteriën in de darm in de loop van een jaar?

- Onderzoek identificeert mechanismen die bacteriële overleving bevorderen

- The Anatomy of the Hydra

- Waarom ernstig bedreigde vrouwelijke walvissen moeite hebben om zich voort te planten

- Gedetailleerd overzicht van oude Britse vogels onthult potentiële kandidaten voor herwildering

- Mysteriegen rijpt het skelet van de cel

- Mutualisme (biologie): definitie, types, feiten en voorbeelden

- Kenmerken van een eencellig organisme

- Waarom wordt natrium gebruikt bij DNA-extractie?

- On-demand diensten brengen het openbaar vervoer naar de buitenwijken

- Robotscheidsrechters komen naar honkbal. Zullen ze doorslaan?

- Mariene verkenningsdetectie met licht en geluid

- Een methode om het aantal neuronen in terugkerende neurale netwerken te verminderen

- Groei in datalekken toont noodzaak overheidsregulering aan

DNA-strengen gebruiken om nieuwe polymeermaterialen te ontwerpen

DNA-strengen gebruiken om nieuwe polymeermaterialen te ontwerpen De effecten van silicium op stoomturbines

De effecten van silicium op stoomturbines  Low-cost luchtvaartmaatschappijen hebben zich het beste aangepast aan COVID-19

Low-cost luchtvaartmaatschappijen hebben zich het beste aangepast aan COVID-19 Hoe COVID-19 de komende jaren van invloed kan zijn op reizen

Hoe COVID-19 de komende jaren van invloed kan zijn op reizen Wetenschapper legt uit hoe smeltend ijs op Antarctica Indonesië beïnvloedt

Wetenschapper legt uit hoe smeltend ijs op Antarctica Indonesië beïnvloedt Onlangs ontdekte planeten niet zo veilig voor stellaire uitbarstingen als eerst werd gedacht

Onlangs ontdekte planeten niet zo veilig voor stellaire uitbarstingen als eerst werd gedacht Glucosamineringen veranderen stervormige fluorescerende kleurstoffen in krachtige sondes voor het afbeelden van kankercellen in drie dimensies

Glucosamineringen veranderen stervormige fluorescerende kleurstoffen in krachtige sondes voor het afbeelden van kankercellen in drie dimensies Wat is een wiskundige uitdrukking?

Wat is een wiskundige uitdrukking?

- Elektronica

- Biologie

- Zonsverduistering

- Wiskunde

- French | Italian | Spanish | Portuguese | Swedish | German | Dutch | Danish | Norway |

-

Wetenschap © https://nl.scienceaq.com