Wetenschap

Kunnen we zonne-energie gebruiken om kunstmest te maken op de boerderij?

Stanford-onderzoekers leiden een inspanning om op duurzame wijze stikstofrijke meststoffen te produceren. Krediet:iStock/yupiyan

Brood wordt vaak de staf van het leven genoemd, maar dat label kan nauwkeuriger worden toegepast op stikstof, het element dat bodembacteriën uit de atmosfeer plukken en chemisch veranderen om de groei van planten te stimuleren, die uiteindelijk ook vee en mensen voeden.

Tegenwoordig bestaat er een enorme industrie voor het produceren en leveren van op stikstof gebaseerde meststoffen aan boerderijen, die profiteren van hogere gewasopbrengsten, maar helaas, tegen wat milieukosten, omdat overtollige chemische afvoer vaak in rivieren en kustwateren terechtkomt.

Nu leiden Stanford-onderzoekers een meerjarige inspanning om deze vitale groeibooster op een duurzame manier te produceren, door een chemische technologie op zonne-energie uit te vinden die deze meststof rechtstreeks op de boerderij kan maken en rechtstreeks op gewassen kan toepassen, druppelirrigatiestijl.

"Ons team ontwikkelt een productieproces voor kunstmest dat de wereld op een ecologisch duurzame manier kan voeden. " zegt chemisch ingenieur Jens Norskov, directeur van het SUNCAT Center for Interface Science and Catalysis, een samenwerking tussen onderzoekers van Stanford Engineering en het SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory.

Dit achtjarige SUNCAT-project wordt ondersteund door een subsidie van $ 7 miljoen van de Villum Foundation, een internationale wetenschappelijke en ecologische filantropie. De duurzame stikstofinspanning maakt deel uit van een breder, $20 miljoen Villum-gesteund initiatief om Stanford-onderzoekers samen te brengen met Deense wetenschappers om duurzame technologieën te ontwikkelen om niet alleen meststoffen te produceren, maar brandstoffen en andere essentiële industriële chemicaliën.

"Een rode draad in deze projecten is de noodzaak om katalysatoren te identificeren die chemische processen kunnen bevorderen die worden aangedreven door zonlicht, in plaats van te vertrouwen op de fossiele brandstoffen die nu algemeen worden gebruikt als energiebronnen en, vaak, als grondstof voor reacties, " zegt Norskov, een professor in chemische technologie en fotonenwetenschap aan Stanford.

Katalysatoren – verbindingen die reacties stimuleren zonder te worden verbruikt – worden al meer dan een eeuw op industriële schaal gebruikt. De meststoffen van tegenwoordig worden gewoonlijk afgeleid van petrochemicaliën via een energie-intensief proces dat afhankelijk is van katalysatoren om reacties die plaatsvinden onder hoge drukken en temperaturen te versnellen. Het ontwikkelen van een energiezuinige, op zonne-energie gebaseerd proces om stikstofmeststoffen te maken, kan miljarden mensen ten goede komen, vooral die in de derde wereld. Maar om daar te komen, zullen SUNCAT-onderzoekers baanbrekend moeten zijn in de wetenschap van katalyse.

"We kennen geen door de mens gemaakte katalysatoren die kunnen doen wat we nodig hebben, ' zegt Norskov. 'We zullen ze moeten ontwerpen.'

Stikstof en leven

Stikstof is letterlijk verweven in het weefsel van het leven. Door chemische combinaties met koolstof, waterstof en zuurstof, stikstof helpt bij het vormen van aminozuren, die zelf de bouwstenen zijn van eiwitten, die veelzijdige familie van moleculen die essentieel zijn voor elk levend wezen. We mogen bodembacteriën bedanken voor het bruikbaar maken van stikstof. In de loop van de tijd ontwikkelden micro-organismen een biochemisch ecosysteem om stikstof uit de atmosfeer te halen en te combineren met waterstof uit water om verbindingen te vormen zoals ammoniak die door planten kunnen worden opgenomen, hun groei te bevorderen en dit atmosferische gas naar de voedselketen te leiden.

We weten niet wanneer boeren voor het eerst de voordelen van bemesting ontdekten, maar de praktijk is oud. Moderne studies van de bodem rond neolithische nederzettingen suggereren dat, al vanaf 6 000 jaar geleden, boeren probeerden de opbrengst te verhogen door gewassen te bemesten met dierlijk afval - waarvan nu bekend is dat het stikstofrijk ureum (ammoniak plus koolstof) bevat. Andere traditionele bemestingspraktijken omvatten het verbouwen van gewassen zoals klaver en luzerne die goed zijn in het fixeren van bruikbare stikstof in de bodem, of simpelweg velden braak laten liggen om bodembacteriën de voorraad van de natuur te laten aanvullen. Overuren, toen de bevolking groeide en naar steden verhuisde, industrieën ontstonden om boeren te voorzien van op stikstof gebaseerde meststoffen. Soms betekende dit het sturen van schepen om guano-afzettingen van vogels op afgelegen eilanden te scheppen, of mijnbouwchemicaliën zoals natriumnitraat of ammoniumsulfaat die kunnen worden geraffineerd tot additieven voor plantengroei.

In het eerste decennium van de 20e eeuw, echter, bevolkingsgroei dreigde dergelijke praktijken te zwaar te belasten. Het was op dit cruciale moment dat de Duitse chemicus Fritz Haber, werken met chemisch ingenieur Carl Bosch, ontdekte hoe ammoniak massaal geproduceerd kon worden in gigantische vaten met behulp van aardgas, wat het startpunt of de grondstof van het proces was. Onder extreme druk en hitte, chemische katalysatoren kunnen aardgasmoleculen kraken, het vrijmaken van de waterstofatomen en het verbinden met stikstof uit de lucht om NH3 te vormen, of synthetische ammoniak die gemakkelijk door planten kan worden opgenomen. De Haber-Bosch-technologie is geprezen als een van de belangrijkste ontdekkingen van de 20e eeuw.

"We voeden de wereld letterlijk met meststoffen die zijn afgeleid van het Haber-Bosch-proces, ' zegt Norskov.

Schaal en milieu-impact

Tom Jaramillo, adjunct-directeur van het SUNCAT Center en lid van het stikstofsyntheseproject, de jaarlijkse kunstmestproductie in perspectief te plaatsen.

"Elk jaar produceren we meer dan 20 kilogram ammoniak per persoon voor elke persoon op de planeet, en het grootste deel van die ammoniak wordt gebruikt voor kunstmest, " zegt Jaramillo, een universitair hoofddocent chemische technologie en fotonenwetenschap aan Stanford.

Maar deze enorme mestproductie heeft verschillende kosten, beginnend met productie Vanwege de hitte en druk die nodig zijn voor het Haber-Bosch-proces, ammoniakkatalyse is goed voor ongeveer 1% van al het wereldwijde energieverbruik. Daarbovenop, tussen 3% en 5% van 's werelds aardgas wordt gebruikt als grondstof voor de waterstof voor de synthese van ammoniak.

Dan komen de milieukosten. De meststoffen van tegenwoordig worden massaal geproduceerd in gecentraliseerde fabrieken, geleverd aan boerderijen en toegediend met behulp van gemechaniseerde strooiers. Regen- en irrigatiewater kunnen overtollige mest in stromen spoelen, rivieren en kustwateren. Ophopingen van afvloeiing van kunstmest kunnen de hypergroei van waterplanten stimuleren, het creëren van een negatieve milieuspiraal waarin de planten het zeeleven kunnen verstikken om "dode zones" in rivieren te creëren, meren en zoutwaterbaaien.

SUNCAT-onderzoekers streven ernaar om de voordelen van bemesting te bieden zonder deze kosten. Het idee is om de gecentraliseerde, Het op fossiele brandstoffen gebaseerde Haber-Bosch-proces met een gedistribueerd netwerk van ammoniak-on-demand productiemodules draaien op hernieuwbare energie. Deze modules zouden zonne-energie gebruiken om stikstof uit de atmosfeer te halen en ook om de splitsing van watermoleculen te katalyseren om waterstof en zuurstof te krijgen. De katalytische processen zouden dan één stikstofatoom met drie waterstofatomen verenigen om ammoniak te produceren, met zuurstof als afvalproduct.

"We zullen zonne-energie gebruiken in de aanwezigheid van goed ontworpen katalysatoren om ammoniak te creëren in de landbouw, " zegt Norskov. "Zie het als een druppelirrigatiemethode om ammoniak te synthetiseren, waar het doorsijpelt in de wortels van de gewassen."

This effort comes as attention is being focused on industrialized agriculture's heavy reliance on fossil fuels and the many environmental ramifications of that dependence.

"You won't need tremendous quantities of fossil fuels as an ammonia feedstock, or to drive the trucks that deliver the fertilizers or the tractors that apply it, " Norskov says. "And you won't have a problem with excess application and fertilizer runoff, because virtually all the fertilizer that is produced will be consumed completely by the crops."

Such a process would have a global payoff. In the developed economies with mechanized agriculture, solar-based nitrogen catalysis would deliver fertilizers with dramatically lower environmental costs. In regions like sub-Saharan Africa, where depleted soils have stymied efforts at sustainable agriculture and reforestation, a solar-based fertilization technology could help subsistence farmers boost crop yields and alleviate hunger.

Next-generation catalysis

Developing a solar-powered technology to produce nitrogen-based fertilizers is an enormous challenge that begins with designing the necessary catalysts.

"It is remarkable how much economic and industrial activity depends on catalysis and how little this is appreciated, " Norskov says.

Catalysts are chemistry's multitaskers:They must target specific molecules, break certain chemical bonds and, often, create new bonds to remake from the atomic jumble whatever end molecule is desired. It is understandably rare to find a chemical agent that can perform all this breaking and making without becoming exhausted – in this case a technical reference to the fact that a catalyst must carry out these chemical reactions without changing the atomic structure that enabled it to perform its multitasking magic in the first place.

"While the catalyst must bind strongly enough to the target molecule to do the work required, it also has to release the end product, " says Stacey Bent, a professor of chemical engineering at Stanford and key member of the SUNCAT team. "We have to design catalysts that can make and break bonds with atomic precision, and we have to ensure these materials can be mass produced at the necessary scales and price points, and are durable and simple to use in the fields."

This is especially true in the case of the fertilizer-production process envisioned here, Jaramillo explains, because of the complexity of the process.

"We have to design a series of reactions to cleave the nitrogen molecule from air, separate the hydrogen from water and combine them to form ammonia, with the only input energy coming from solar power, " Jaramillo says, toevoegen, "We're really just at the beginning."

Computation, visualization, experimenteren

The close working relationship between Stanford engineers and researchers at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is an important part of the story.

SLAC particle accelerators and imaging technologies can capture and visualize chemical reactions at the atomic scale. Dat, in combination with SLAC's computational assets, will allow the SUNCAT team to use a variety of techniques, including artificial intelligence, machine learning and simulation, to identify promising materials, and then predict how slight alterations to their atomic structures might optimize them for use as catalysts.

"We plan to simulate the properties of materials that could perform the necessary reactions, " says Bent, "and then come up with a short list of the best candidates for experimentalists to synthesize and test."

The magnitude of the task requires a wide range of talents. In addition to Norskov, Jaramillo and Bent, other participating Stanford researchers include chemical engineering faculty Zhenan Bao and Matteo Cargnello. SLAC collaborators include Thomas Bligaard, senior staff scientist and deputy director of theory at SUNCAT, and staff scientist Frank Abild-Pedersen. A group of Danish researchers led by professor Ib Chorkendorff at the Technical University of Denmark are key members of the project.

"We are part of a very strong team, attacking some of the biggest challenges in chemistry, chemical engineering and sustainability, " says Jaramillo.

The ultimate goal is to create a catalytic process that can spur the various ammonia-producing chemical reactions with no inputs other than air, water and sunlight. Bovendien, these inexhaustible catalysts, and indeed every component in these ammonia-production modules, must be inexpensive to mass produce, durable in the field and easy to operate. It's a tall order but the potential payoff is huge.

"Sustainable nitrogen production will only become possible with the cross-disciplinary collaboration of people working in fields such as materials science, chemical engineering and computer science, " Bent says. "It could literally change the world."

If the project's goal seems worth the effort, the same is true for its research methodology. Team-based discovery that combines theoretical insight, atomic-level visualization and computational simulation can be applied to designing other sustainable processes to create fuels and industrial chemicals, as envisioned by the broader Villum initiative.

Norskov framed that broader objective against the backdrop of global warming in a recent paper co-authored with Arun Majumdar, a professor of mechanical engineering at Stanford, co-director of the Precourt Institute for Energy and former founding director of the Advanced Research Projects Agency–Energy.

In an essay for the Scientific Philanthropy Alliance, Norskov and Majumdar posit that civilization has reached the point at which the technologies that have allowed our population to grow may now threaten life's underpinnings. The essential challenge of the 21st century is to develop new technologies that meet human needs in ways that are environmentally sustainable.

"Essentially we are attempting to restore the balance in the Earth's carbon and nitrogen cycles that has been lost through the exponential increase in the demand for food and fossil fuels, " Norskov and Majumdar write, toevoegen, "The time to act is now."

Hoofdlijnen

- Onderzoekers willen weten waarom beluga-walvissen nog niet zijn hersteld

- Genetische modificatie: definitie, soorten, proces, voorbeelden

- Fun Biology Presentatie Onderwerpen

- Wat zijn enkele kenmerken van DNA?

- Eenvoudige manieren om de structuren van de Skull

- Ontdekking van gewasgenen raakt de wortel van voedselzekerheid

- Een natte winter kan de invasieve soorten van San Francisco Bay opschudden

- Hoe ribosomen het proteoom vormen

- Een onwaarschijnlijke held vergiftigen bij het afweren van exotische indringers?

- Hogesnelheidsfilm helpt wetenschappers bij het ontwerpen van gloeiende moleculen

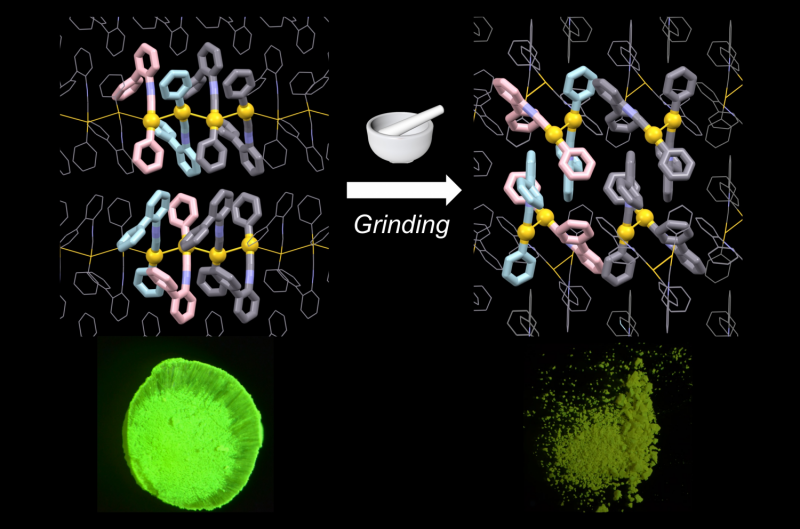

- Nieuwe strategie om mechanisch reagerende lichtgevende materialen te ontwerpen

- Stuifmeel omzetten in 3D-printinkt voor biomedische toepassingen

- Nieuwe sensortechnologie maakt supergevoelige live monitoring van menselijke biomoleculen mogelijk

- Stam gebruiken om oxynitride-eigenschappen te beheersen

Een bijna enkelvoudige matrix corrigeren

Een bijna enkelvoudige matrix corrigeren  Dieren in de Middellandse Zee

Dieren in de Middellandse Zee  NASA-beelden tonen ongeorganiseerde tropische depressie 8E

NASA-beelden tonen ongeorganiseerde tropische depressie 8E Indiase brandweerlieden strijden tegen luchtvervuiling in New Delhi

Indiase brandweerlieden strijden tegen luchtvervuiling in New Delhi In een eerste, onderzoekers identificeren roodachtige kleuren in een oud fossiel

In een eerste, onderzoekers identificeren roodachtige kleuren in een oud fossiel Spookachtige sporen van enorme oude rivier onthuld

Spookachtige sporen van enorme oude rivier onthuld Honderdduizenden mensen kiezen namen voor exoplaneetsystemen

Honderdduizenden mensen kiezen namen voor exoplaneetsystemen Vervuiling bij Cape Fear River

Vervuiling bij Cape Fear River

- Elektronica

- Biologie

- Zonsverduistering

- Wiskunde

- French | Spanish | Swedish | German | Dutch | Danish | Norway | Italian | Portuguese |

-

Wetenschap © https://nl.scienceaq.com