Wetenschap

Nanoratels zorgen voor nieuwe mogelijkheden voor ziektedetectie

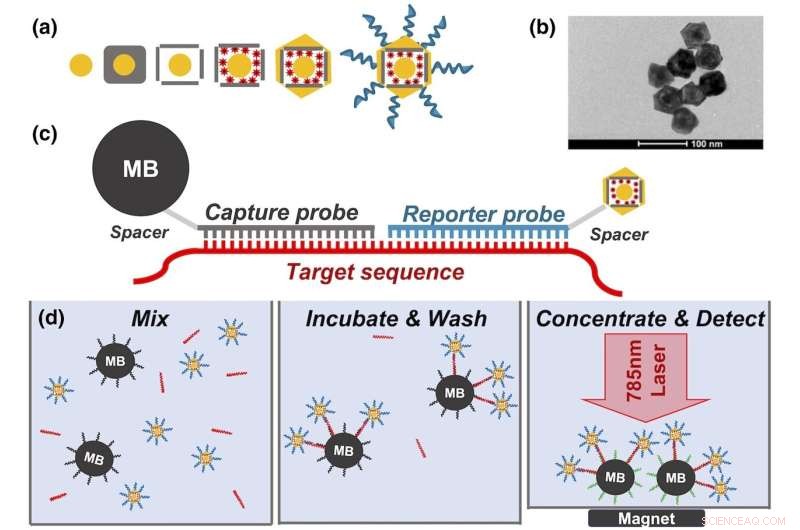

(a) Stappen in nanorattle-synthese:20 nm Au-bollen, groei van Ag-kubus, galvanische vervanging resulterend in Au@Ag-kooi, kleurstoflading, uiteindelijke Au-coating en DNA-probe-functionalisatie. (b) TEM van nanorammelaar. (c) Hybridisatieschema van hybridisatietest met nanorattle en magnetische kralen. (d) Nanorattle-teststappen:meng magnetische kralen, nanorattles en doelwit; incuberen; concentreren; en detecteren. TEM, transmissie-elektronenmicroscopie. Krediet:Journal of Raman Spectroscopy (2022). DOI:10.1002/jrs.6447

Onderzoekers van de Duke University hebben een uniek type nanodeeltje ontwikkeld, een 'nanorattle' genaamd, dat het licht dat wordt uitgestraald vanuit de buitenste schil aanzienlijk verbetert.

Geladen met lichtverstrooiende kleurstoffen, Raman-reporters genaamd, die vaak worden gebruikt om biomarkers van ziekte in organische monsters te detecteren, kan de aanpak signalen van verschillende soorten nanosondes versterken en detecteren zonder dat een dure machine of medische professional nodig is om de resultaten te lezen.

In een kleine proof-of-concept-studie identificeerden de nanorattles nauwkeurig hoofd- en nekkankers via een AI-enabled point-of-care-apparaat dat een revolutie teweeg kan brengen in de manier waarop deze kankers en andere ziekten worden gedetecteerd in gebieden met weinig middelen om de wereldwijde gezondheid te verbeteren.

De resultaten verschenen op 2 september online in het Journal of Raman Spectroscopy .

"Het concept om Raman-reporters in deze zogenaamde nanorattles te vangen, is al eerder gedaan, maar de meeste platforms hadden moeite om de binnenafmetingen te beheersen", zegt Tuan Vo-Dinh, de R. Eugene en Susie E. Goodson Distinguished Professor of Biomedical Engineering bij Hertog.

"Onze groep heeft een nieuw type sonde ontwikkeld met een nauwkeurig afstembare opening tussen de binnenste kern en de buitenste schil, waardoor we meerdere soorten Raman-reporters kunnen laden en hun emissie van licht, oppervlakteversterkte Raman-verstrooiing genaamd, kunnen versterken," Vo-Dinh zei.

Om nanorammelaars te maken, beginnen onderzoekers met een massief gouden bol van ongeveer 20 nanometer breed. Nadat ze een laag zilver rond de gouden kern hebben aangebracht om een grotere bol (of kubus) te maken, gebruiken ze een corrosieproces dat galvanische vervanging wordt genoemd en dat het zilver uitholt, waardoor een kooiachtige schaal rond de kern ontstaat. De structuur wordt vervolgens gedrenkt in een oplossing die positief geladen Raman-reporters bevat, die door de negatief geladen gouden kern in de buitenste kooi worden getrokken. De buitenste rompen worden dan bedekt met een extreem dunne laag goud om de Raman-reporters binnenin op te sluiten.

Het resultaat is een nanosfeer (of nanokubus) van ongeveer 60 nanometer breed met een architectuur die lijkt op een rammelaar - een gouden kern die is opgesloten in een grotere buitenste zilver-gouden schaal. De kloof tussen de twee is slechts enkele nanometers, net groot genoeg voor de Raman-reporters.

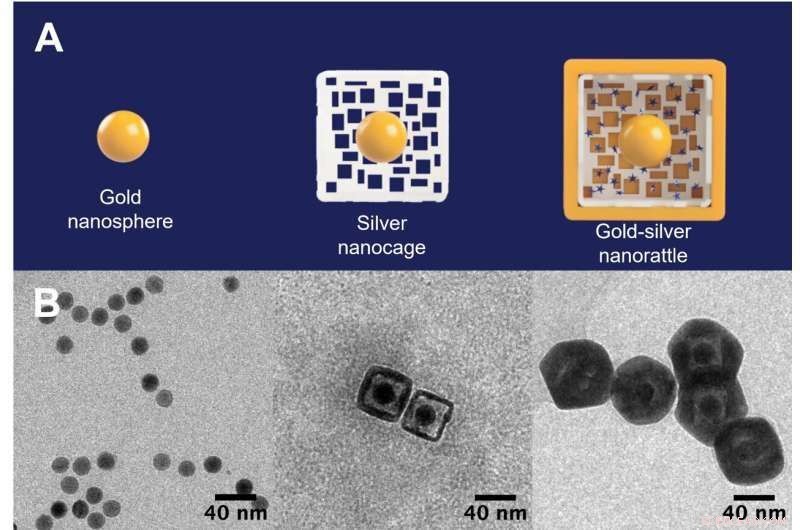

De beginnende gouden nanosfeerzaden (links) zijn omgeven door een holle, poreuze zilveren kooi (midden) en worden een nanorammelaar gevuld met lichtverstrooiende kleurstoffen in een gouden buitenste schil (rechts). De nanoratels kunnen signalen van verschillende soorten nanosondes versterken en detecteren zonder dat een dure machine of medische professional nodig is om de resultaten te lezen. Krediet:Tuan Vo-Dinh, Duke University

Die nauwe toleranties zijn essentieel voor het beheersen van de Raman-signaalversterking die de nanorammelaars produceren.

When a laser shines on the nanorattles, it travels through the extremely thin outer shell and hits the Raman reporters within, causing them to emit light of their own. Because of how close the surfaces of the gold core and the outer gold/silver shell are together, the laser also excites groups of electrons on the metallic structures, called plasmons. These groups of electrons create an extremely powerful electromagnetic field due to the plasmons' interaction of the metallic core-shell architecture, a process called plasmonic coupling, which amplifies the light emitted by the Raman reporters millions of times over.

"Once we had the nanorattles working, we wanted to make biosensing devices to detect infectious diseases or cancers before people even know they're sick," Vo-Dinh said. "With how powerful the signal enhancement of the nanorattles is, we thought we could make a simple test that could be easily read by anybody at the point-of-care."

In the new paper, Vo-Dinh and his collaborators apply the nanorattle technology to a lab-on-a-stick device capable of detecting head and neck cancers, which appear anywhere between the shoulders and the brain, typically in the mouth, nose and throat. Survival rate for these cancers have hovered between 40 and 60 percent for decades. While those statistics have improved in recent years in the United States, they have gotten worse in low-resource settings, where risk factors such as smoking, drinking and betel nut chewing are much more prevalent.

"In low-resource settings, these cancers often present in advanced stages and result in poor outcomes due in part to limited examination equipment, lack of trained healthcare workers and essentially non-existent screening programs," said Walter Lee, professor of head and neck surgery and communication sciences and radiation oncology at Duke, and a collaborator on the research.

"Having the ability to detect these cancers early should lead to earlier treatment and improvement in outcomes, both in survival and quality of life," Lee said. "This approach is exciting since it does not depend on a pathologist review and potentially could be used at the point of care."

The prototype device uses specific genetic sequences that act like Velcro for the biomarkers the researchers are looking for—in this case, a specific mRNA that is overly abundant in people with head and neck cancers. When the mRNA in question is present, it acts like a tether that binds nanorattles to magnetic beads. These beads are then concentrated and held in place by another magnet while everything else gets rinsed away. Researchers can then use a simple, inexpensive handheld device to look for light emitted from the nanorattles to see if any biomarkers were caught.

In the experiments, the test determined whether or not 20 samples came from patients that had head and neck cancer with 100% accuracy. The experiments also showed that the nanorattle platform is capable of handling multiple types of nanoprobes, thanks to a machine learning algorithm that can tease apart the separate signals, meaning they can target multiple biomarkers at once. This is the goal of the group's current project funded by the National Institutes of Health.

"Many mRNA biomarkers are overly abundant in multiple types of cancers, while other biomarkers can be used to evaluate patient risk and future treatment outcome," Vo-Dinh said. "Detecting multiple biomarkers at once would help us differentiate between cancers, and also look for other prognostic markers such as Human Papillomavirus (HPV), and both positive and negative controls. Combining mRNA detection with novel nanorattle biosensing will result in a paradigm shift in achieving a diagnostic tool that could revolutionize how these cancers and other diseases are detected in low-resource areas." + Verder verkennen

Silver-plated gold nanostars detect early cancer biomarkers

Wat is de vergelijking van de fotosynthese?

Wat is de vergelijking van de fotosynthese?  Een piepschuim maken Kaliumatomen voor school

Een piepschuim maken Kaliumatomen voor school Kooldioxide transformeren

Kooldioxide transformeren Neutronen onderzoeken zuurstofgenererend enzym voor een groenere benadering van schoon water

Neutronen onderzoeken zuurstofgenererend enzym voor een groenere benadering van schoon water Wetenschappers stellen een flexibel interface-ontwerp voor een silicium-grafiet dual-ion batterij voor

Wetenschappers stellen een flexibel interface-ontwerp voor een silicium-grafiet dual-ion batterij voor

Arctic was ooit weelderig en groen, en zou weer kunnen zijn, nieuw onderzoek toont aan

Arctic was ooit weelderig en groen, en zou weer kunnen zijn, nieuw onderzoek toont aan Een iets warmer kantoor maakt het niet te warm om na te denken

Een iets warmer kantoor maakt het niet te warm om na te denken Waarom zwemmen zalm en andere vissen stroomopwaarts?

Waarom zwemmen zalm en andere vissen stroomopwaarts?  Warmere winters zorgen ervoor dat sommige meren niet bevriezen

Warmere winters zorgen ervoor dat sommige meren niet bevriezen Bloomageddon - zeven slimme manieren waarop boshyacinten de oorlog in het bos winnen

Bloomageddon - zeven slimme manieren waarop boshyacinten de oorlog in het bos winnen

Hoofdlijnen

- Landbouwproductiviteit dreef de Euro-Amerikaanse nederzetting van Utah

- Hoe wordt recombinant DNA gemaakt?

- De definitie van moleculaire celbiologie

- Bee it bekend:Biodiversiteit is van cruciaal belang voor ecosystemen

- Je hoeft geen schattige koala te zijn om een Instagram-beïnvloeder te zijn. Geef hagedissen en insecten een kans

- Is intelligentie een genetisch kenmerk?

- Drie van de meest bizarre relaties van de natuur

- Onderzoekers identificeren Ku-eiwitten als nieuwe co-sensoren van cyclische GMP-AMP-synthase

- T-cellen gebruiken geweld om kankercellen te vernietigen

- Onderzoekers onthullen waarom nanodraden aan elkaar kleven

- Grafeen kan de weg vrijmaken voor Australische productie

- Snelle afbraak van verontreinigende stoffen door nanosheets

- Wetenschappers tonen de kwetsbaarheid van een veelbelovende tweedimensionale halfgeleider voor lucht, en ontdek nieuwe katalysator

- Beperken tot massaproductie van nanotechnologie?

Kooi met doppen:selectieve opsluiting van hydraten van zeldzame aardmetalen in gastheermoleculen

Kooi met doppen:selectieve opsluiting van hydraten van zeldzame aardmetalen in gastheermoleculen Geminiaturiseerde massaspectrometer voor verkenning van Mars heeft een enorm potentieel

Geminiaturiseerde massaspectrometer voor verkenning van Mars heeft een enorm potentieel Een legering die zijn geheugen behoudt bij hoge temperaturen

Een legering die zijn geheugen behoudt bij hoge temperaturen Segregatie en lokale financieringstekorten zorgen voor verschillen in drinkwater

Segregatie en lokale financieringstekorten zorgen voor verschillen in drinkwater SARS-CoV-2 in vaste stoffen in afvalwater kan de verspreiding van COVID-19 helpen monitoren

SARS-CoV-2 in vaste stoffen in afvalwater kan de verspreiding van COVID-19 helpen monitoren Afbeelding:Atlantische scheepssporen

Afbeelding:Atlantische scheepssporen Een populatie-gemiddelde

Een populatie-gemiddelde op een dag, zelfs natte bossen kunnen verbranden door klimaatverandering

op een dag, zelfs natte bossen kunnen verbranden door klimaatverandering

- Elektronica

- Biologie

- Zonsverduistering

- Wiskunde

- French | Italian | Spanish | Portuguese | Swedish | German | Dutch | Danish | Norway |

-

Wetenschap © https://nl.scienceaq.com