Wetenschap

Hulp nodig bij het bouwen van IKEA-meubels? Deze robot kan een handje helpen

Een online schapspel, ontwikkeld als proof-of-concept. Krediet:Universiteit van Zuid-Californië

Naarmate robots steeds meer hun krachten bundelen om met mensen te werken - van verpleeghuizen tot magazijnen tot fabrieken - moeten ze proactief ondersteuning kunnen bieden. Maar eerst moeten robots iets leren dat we instinctief weten:hoe te anticiperen op de behoeften van mensen.

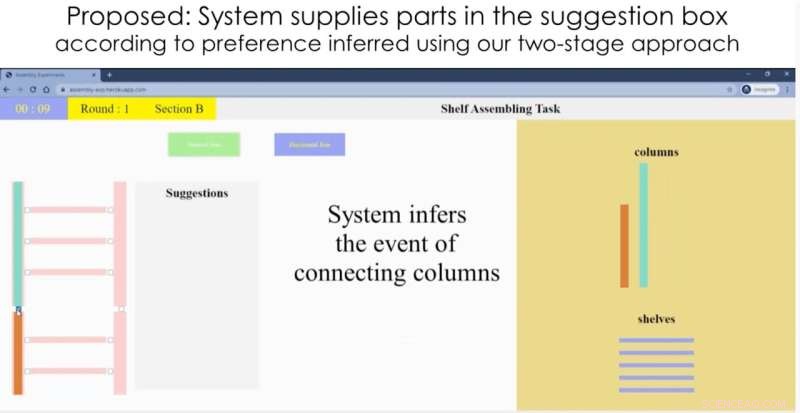

Met dat doel voor ogen hebben onderzoekers van de USC Viterbi School of Engineering een nieuw robotsysteem ontwikkeld dat nauwkeurig voorspelt hoe een mens een IKEA-boekenkast zal bouwen en vervolgens een handje helpt - door de plank, bout of schroef te leveren die nodig is om de taak te voltooien . Het onderzoek werd gepresenteerd op de International Conference on Robotics and Automation op 30 mei 2021.

"We willen dat mens en robot samenwerken - een robot kan je helpen dingen sneller en beter te doen door ondersteunende taken uit te voeren, zoals dingen ophalen", zegt hoofdauteur Heramb Nemlekar van het onderzoek. "Mensen zullen nog steeds de primaire acties uitvoeren, maar kunnen eenvoudigere secundaire acties overdragen aan de robot."

Nemlekar, een Ph.D. student in computerwetenschappen, wordt begeleid door Stefanos Nikolaidis, een assistent-professor in de computerwetenschappen, en co-auteur van het artikel met Nikolaidis en SK Gupta, een professor in lucht- en ruimtevaart, werktuigbouwkunde en informatica die het Smith International Professorship in Mechanical Engineering bekleedt.

Aanpassen aan variaties

In 2018 leerde een door onderzoekers in Singapore gemaakte robot om zelf een IKEA-stoel in elkaar te zetten. In deze nieuwe studie wil het USC-onderzoeksteam zich in plaats daarvan concentreren op de samenwerking tussen mens en robot.

Het combineren van menselijke intelligentie en robotkracht heeft voordelen. In een fabriek kan een menselijke operator bijvoorbeeld de productie aansturen en bewaken, terwijl de robot het fysiek zware werk doet. Mensen zijn ook meer bedreven in die lastige, delicate taken, zoals een schroef ronddraaien om het passend te maken.

The key challenge to overcome:humans tend to perform actions in different orders. For instance, imagine you're building a bookcase—do you tackle the easy tasks first, or go straight for the difficult ones? How does the robot helper quickly adapt to variations in its human partners?

"Humans can verbally tell the robot what they need, but that's not efficient," said Nikolaidis. "We want the robot to be able to infer what the human wants, based on some prior knowledge."

It turns out, robots can gather knowledge much like we do as humans:by "watching" people, and seeing how they behave. While we all tackle tasks in different ways, people tend to cluster around a handful of dominant preferences. If the robot can learn these preferences, it has a head start on predicting what you might do next.

A good collaborator

Based on this knowledge, the team developed an algorithm that uses artificial intelligence to classify people into dominant "preference groups," or types, based on their actions. The robot was fed a kind of "manual" on humans:data gathered from an annotated video of 20 people assembling the bookcase. The researchers found people fell into four dominant preference groups.

In an IKEA furniture assembly task, a human stayed in a “work area” and performed the assembling actions, while the robot brought the required materials from storage area. Krediet:Universiteit van Zuid-Californië

For instance, do you connect all the shelves to the frame on just one side first; or do you connect each shelf to the frame on both sides, before moving onto the next shelf? Depending on your preference category, the robot should bring you a new shelf, or a new set of screws. In a real-life IKEA furniture assembly task, a human stayed in a "work area" and assembled the bookcase, while the robot—a Kinova Gen 2 robot arm—learned the human's preferences, and brought the required materials from a storage area.

"The system very quickly associates a new user with a preference, with only a few actions," said Nemlekar.

"That's what we do as humans. If I want to work to work with you, I'm not going to start from zero. I'll watch what you do, and then infer from that what you might do next."

In this initial version, the researchers entered each action into the robotic system manually, but future iterations could learn by "watching" the human partner using computer vision. The team is also working on a new test-case:humans and robots working together to build—and then fly—a model airplane, a task requiring close attention to detail.

Refining the system is a step towards having "intuitive" helper robots in our daily lives, said Nikolaidis. Although the focus is currently on collaborative manufacturing, the same insights could be used to help people with disabilities, with applications including robot-assisted eating or meal prep.

"If we will soon have robots in our homes, in our work, in care facilities, it's important for robots to infer and adapt to people's preferences," said Nikolaidis. "The robot needs to be a teammate and a good collaborator. I think having some notion of user preference and being able to learn variability is what will make robots more accepted."

Moleculaire simulaties gebruiken om zelf-assemblerende, associërende polymeren te bestuderen

Moleculaire simulaties gebruiken om zelf-assemblerende, associërende polymeren te bestuderen Kankercellen vernietigd met metaal van de asteroïde die de dinosauriërs heeft gedood

Kankercellen vernietigd met metaal van de asteroïde die de dinosauriërs heeft gedood Water efficiënter omzetten in waterstof

Water efficiënter omzetten in waterstof Efficiënte perovskiet fotovoltaïsche energie optimaliseren

Efficiënte perovskiet fotovoltaïsche energie optimaliseren Visslijm:een onaangeboorde bron van potentiële nieuwe antibiotica

Visslijm:een onaangeboorde bron van potentiële nieuwe antibiotica

Waardoor komt er een einde aan een ijstijd?

Waardoor komt er een einde aan een ijstijd? Veranderingen in regenval en temperaturen hebben al invloed gehad op de waterkwaliteit

Veranderingen in regenval en temperaturen hebben al invloed gehad op de waterkwaliteit Hoe de opwarming van de aarde de Noord-Amerikaanse moesson opdroogt

Hoe de opwarming van de aarde de Noord-Amerikaanse moesson opdroogt Kaarten om schattingen van bosbiomassa te verbeteren

Kaarten om schattingen van bosbiomassa te verbeteren Atmosferische ijsdeeltjes kleiner en vallen sneller dan modellen hadden aangenomen

Atmosferische ijsdeeltjes kleiner en vallen sneller dan modellen hadden aangenomen

Hoofdlijnen

- "What is Pascals Triangle?

- Drie decennia van onderzoek mondt uit in meer unieke orchideeënsoorten

- Hoe de droogrot Serpula lacrymans zich aanpasten aan een nieuwe ecologische habitat

- Vroegtijdige waarschuwing gezondheids- en welzijnssysteem kan boeren miljoenen ponden besparen

- Ethics of Genetic Engineering

- Mensen zijn geëvolueerd met hun microbioom. Net als genen gaan je darmmicroben van de ene generatie naar de volgende

- Hoe een cel te splitsen in Two

- Wat is bioculturele diversiteit en waarom is het belangrijk?

- Hoe noteer ik een Karyotype

- Technologie helpt de energiekosten op de boerderij in Indiana te verlagen en tegelijkertijd het milieu te beschermen

- Russische techgigant Yandex onthult eerste smartphone

- Taxi's in Madrid sluiten zich aan bij staking Barcelona tegen Uber

- Hoe Nantes teams 3D-printen de vorm van toekomstige huizen kan veranderen

- Robots kunnen toekomstige boerderijen runnen, onderzoekers zeggen:

Ozonvervuiling bedreigt de gezondheid van planten en maakt het voor bestuivers moeilijker om bloemen te vinden

Ozonvervuiling bedreigt de gezondheid van planten en maakt het voor bestuivers moeilijker om bloemen te vinden Vitale tekens:de kracht van niet te duidelijk zijn

Vitale tekens:de kracht van niet te duidelijk zijn Synthetische lava in laboratorium helpt bij het verkennen van exoplaneten

Synthetische lava in laboratorium helpt bij het verkennen van exoplaneten De regels overtreden:zware chemische elementen veranderen de theorie van de kwantummechanica

De regels overtreden:zware chemische elementen veranderen de theorie van de kwantummechanica Afbeelding:Elfde commerciële bevoorradingsmissie van SpaceX naar ruimtestation klaar voor lancering

Afbeelding:Elfde commerciële bevoorradingsmissie van SpaceX naar ruimtestation klaar voor lancering Dikke mobiele apparaten? Zacht grafeen kan je helpen inkrimpen

Dikke mobiele apparaten? Zacht grafeen kan je helpen inkrimpen Kagome-spinijs realiseren in een gefrustreerde intermetallische verbinding

Kagome-spinijs realiseren in een gefrustreerde intermetallische verbinding Wat zijn de kenmerken van overstromingen?

Wat zijn de kenmerken van overstromingen?

- Elektronica

- Biologie

- Zonsverduistering

- Wiskunde

- French | Italian | Spanish | Portuguese | Swedish | German | Dutch | Danish | Norway |

-

Wetenschap © https://nl.scienceaq.com