Wetenschap

Gas bereikt jonge sterren langs magnetische veldlijnen

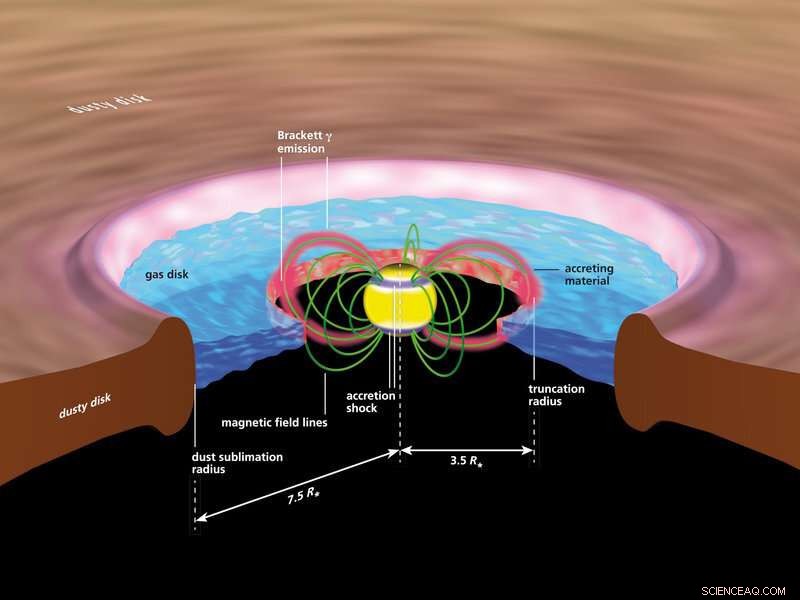

Artistieke impressie van de hete gasstromen die jonge sterren helpen groeien. Magnetische velden leiden materie van de omringende circumstellaire schijf, de geboorteplaats van de planeten, naar het oppervlak van de ster, waar ze intense uitbarstingen van straling produceren. Krediet:A. Mark Garlick

Astronomen hebben het GRAVITY-instrument gebruikt om de directe omgeving van een jonge ster gedetailleerder dan ooit tevoren te bestuderen. Hun waarnemingen bevestigen een dertig jaar oude theorie over de groei van jonge sterren:het magnetische veld dat door de ster zelf wordt geproduceerd, stuurt materiaal van een omringende accretieschijf van gas en stof naar het oppervlak. De resultaten, vandaag gepubliceerd in het tijdschrift Natuur , astronomen helpen beter te begrijpen hoe sterren zoals onze zon worden gevormd en hoe aardachtige planeten worden geproduceerd uit de schijven rond deze stellaire baby's.

Wanneer sterren worden gevormd, ze beginnen relatief klein en bevinden zich diep in een gaswolk. In de loop van de volgende honderdduizenden jaren, ze trekken steeds meer van het omringende gas naar zich toe, het vergroten van hun massa in het proces. Met behulp van het GRAVITY-instrument, een groep onderzoekers waaronder astronomen en ingenieurs van het Max Planck Institute for Astronomy (MPIA), heeft nu het meest directe bewijs gevonden voor hoe dat gas naar jonge sterren wordt geleid:het wordt door het magnetische veld van de ster in een smalle kolom naar het oppervlak geleid.

De relevante lengteschalen zijn zo klein dat zelfs met de beste telescopen die momenteel beschikbaar zijn geen gedetailleerde beelden van het proces mogelijk zijn. Nog altijd, met behulp van de nieuwste observatietechnologie, astronomen kunnen op zijn minst wat informatie verzamelen. Voor de nieuwe studie de onderzoekers maakten gebruik van het buitengewoon hoge oplossend vermogen van het instrument GRAVITY. Het combineert vier 8-meter VLT-telescopen van de European Southern Observatory (ESO) op het Paranal-observatorium in Chili tot een virtuele telescoop die kleine details kan onderscheiden, evenals een telescoop met een 100-meter-spiegel.

ZWAARTEKRACHT gebruiken, de onderzoekers waren in staat om het binnenste deel van de gasschijf rond de ster TW Hydrae te observeren. "Deze ster is speciaal omdat hij heel dicht bij de aarde staat op slechts 196 lichtjaar afstand, en de schijf van materie die de ster omringt, is recht tegenover ons, " zegt Rebeca García López (Max Planck Instituut voor Astronomie, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies en University College Dublin), hoofdauteur en vooraanstaande wetenschapper van deze studie. "Dit maakt het een ideale kandidaat om te onderzoeken hoe materie van een planeetvormende schijf naar het stellaire oppervlak wordt gekanaliseerd."

De waarneming stelde de astronomen in staat om aan te tonen dat nabij-infraroodstraling die door het hele systeem wordt uitgezonden, inderdaad afkomstig is uit het binnenste gebied, waar waterstofgas op het oppervlak van de ster valt. De resultaten wijzen duidelijk in de richting van een proces dat bekend staat als magnetosferische accretie, dat is, invallende materie geleid door het magnetische veld van de ster.

Sterrengeboorte en sterrengroei

Een ster wordt geboren wanneer een dicht gebied binnen een wolk van moleculair gas instort onder zijn eigen zwaartekracht, wordt aanzienlijk dichter, warmt tijdens het proces op, totdat uiteindelijk de dichtheid en temperatuur in de resulterende protoster zo hoog zijn dat de kernfusie van waterstof tot helium begint. Voor protosterren tot ongeveer twee keer de massa van de zon, de ongeveer tien miljoen jaar direct voor de ontsteking van proton-proton kernfusie vormen de zogenaamde T Tauri-fase (genoemd naar de eerste waargenomen ster van dit soort, T Tauri in het sterrenbeeld Stier).

Sterren die we in die fase van hun ontwikkeling zien, bekend als T Tauri-sterren, heel helder schijnen, in het bijzonder in infrarood licht. Deze zogenaamde "jonge stellaire objecten" (YSO's) hebben hun uiteindelijke massa nog niet bereikt:ze zijn omgeven door de overblijfselen van de wolk waaruit ze zijn geboren, in het bijzonder door gas dat is samengetrokken tot een circumstellaire schijf rond de ster. In de buitenste regionen van die schijf, stof en gas klonteren samen en vormen steeds grotere lichamen, die uiteindelijk planeten zullen worden. Grote hoeveelheden gas en stof uit het binnenste schijfgebied, anderzijds, worden op de ster getrokken, zijn massa vergroten. Tenslotte, de intense straling van de ster verdrijft een aanzienlijk deel van het gas als een stellaire wind.

Richtlijnen naar het oppervlak:het magnetische veld van de ster

Naief, men zou kunnen denken dat het transporteren van gas of stof op een massieve, zwaartekrachtlichaam is eenvoudig. In plaats daarvan, het blijkt helemaal niet zo eenvoudig te zijn. Vanwege wat natuurkundigen het behoud van impulsmoment noemen, het is veel natuurlijker dat elk object - of het nu een planeet of een gaswolk is - om een massa draait dan om rechtstreeks op het oppervlak te vallen. Een van de redenen waarom sommige materie toch de oppervlakte weet te bereiken, is een zogenaamde accretieschijf, waarin gas om de centrale massa draait. There is plenty of internal friction inside that continually allows some of the gas to transfer its angular momentum to other portions of gas and move further inward. Nog, at a distance from the star of less than 10 times the stellar radius, the accretion process gets more complex. Traversing that last distance is tricky.

Thirty years ago, Max Camenzind, at the Landessternwarte Königstuhl (which has since become a part of the University of Heidelberg), proposed a solution to this problem. Stars typically have magnetic fields—those of our Sun, bijvoorbeeld, regularly accelerate electrically charged particles in our direction, leading to the phenomenon of Northern or Southern lights. In what has become known as magnetospheric accretion, the magnetic fields of the young stellar object guide gas from the inner rim of the circumstellar disk to the surface in distinct column-like flows, helping them to shed angular momentum in a way that allows the gas to flow onto the star.

In the simplest scenario, the magnetic field looks similar to that of the Earth. Gas from the inner rim of the disk would be funneled to the magnetic North and to the magnetic South pole of the star.

Checking up on magnetospheric accretion

Having a model that explains certain physical processes is one thing. Echter, it is important to be able to test that model using observations. But the length scales in question are of the order of stellar radii, very small on astronomical scales. Until recently, such length scales were too small, even around the nearest young stars, for astronomers to be able to take a picture showing all relevant details.

Schematic representation of the process of magnetospheric accretion of material onto a young star. Magnetic fields produced by the young star carry gas through flow channels from the disk to the polar regions of the star. The ionized hydrogen gas emits intense infrared radiation. When the gas hits the star's surface, shocks occur that give rise to the star's high brightness. Credit:MPIA graphics department

First indication that magnetospheric accretion is indeed present came from examining the spectra of some T Tauri stars. Spectra of gas clouds contain information about the motion of the gas. For some T Tauri stars, spectra revealed disk material falling onto the stellar surface with velocities as high as several hundred kilometers per second, providing indirect evidence for the presence of accretion flows along magnetic field lines. In a few cases, the strength of the magnetic field close to a T Tauri star could be directly measured by a combining high-resolution spectra and polarimetry, which records the orientation of the electromagnetic waves we receive from an object.

Recenter, instruments have become sufficiently advanced—more specifically:have reached sufficiently high resolution, a sufficiently good capability to discern small details—so as to allow direct observations that provide insights into magnetospheric accretion.

The instrument GRAVITY plays a key role here. It was developed by a consortium that includes the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, led by the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics. In operation since 2016, GRAVITY links the four 8-meter-telescopes of the VLT, located at the Paranal observatory of the European Southern Observatory (ESO). The instrument uses a special technique known as interferometry. The result is that GRAVITY can distinguish details so small as if the observations were made by a single telescope with a 100-m mirror.

Catching magnetic funnels in the act

In the Summer of 2019, a team of astronomers led by Jerome Bouvier of the University of Grenobles Alpes used GRAVITY to probe the inner regions of the T Tauri Star with the designation DoAr 44. It denotes the 44th T Tauri star in a nearby star forming region in the constellation Ophiuchus, catalogued in the late 1950s by the Georgian astronomer Madona Dolidze and the Armenian astronomer Marat Arakelyan. The system in question emits considerable light at a wavelength that is characteristic for highly excited hydrogen. Energetic ultraviolet radiation from the star ionizes individual hydrogen atoms in the accretion disk orbiting the star.

The magnetic field then influences the electrically charged hydrogen nuclei (each a single proton). The details of the physical processes that heat the hydrogen gas as it moves along the accretion current towards the star are not yet understood. The observed greatly broadened spectral lines show that heating occurs.

For the GRAVITY observations, the angular resolution was sufficiently high to show that the light was not produced in the circumstellar disk, but closer to the star's surface. Bovendien, the source of that particular light was shifted slightly relative to the centre of the star itself. Both properties are consistent with the light being emitted near one end of a magnetic funnel, where the infalling hydrogen gas collides with the surface of the star. Those results have been published in an article in the journal Astronomie en astrofysica .

The new results, which have now been published in the journal Nature , go one step further. In dit geval, the GRAVITY observations targeted the T Tauri star TW Hydrae, a young star in the constellation Hydra. They are based on GRAVITY observations of the T Tauri star TW Hydrae, a young star in the constellation Hydra. It is probably the best-studied system of its kind.

Too small to be part of the disk

With those observations, Rebeca García López and her colleagues have pushed the boundaries even further inwards. GRAVITY could see the emissions corresponding to the line associated with highly excited hydrogen (Brackett-γ, Brγ) and demonstrate that they stem from a region no more than 3.5 times the radius of the star across (about 3 million km, or 8 times the distance the distance between the Earth and the Moon).

This is a significant difference. According to all physics-based models, the inner rim of a circumstellar disk cannot possibly be that close to the star. If the light originates from that region, it cannot be emitted from any section of the disk. At that distance, the light also cannot be due to a stellar wind blown away by the young stellar object—the only other realistic possibility. Bij elkaar genomen, what is left as a plausible explanation is the magnetospheric accretion model.

Wat is het volgende?

In future observations, again using GRAVITY, the researchers will try to get data that allows them a more detailed reconstruction of physical processes close to the star. "By observing the location of the funnel's lower endpoint over time, we hope to pick up clues as to how distant the magnetic North and South poles are from the star's axis of rotation, " explains Wolfgang Brandner, co-author and scientist at MPIA. If North and South Pole directly aligned with the rotation axis, their position over time would not change at all.

They also hope to pick up clues as to whether the star's magnetic field is really as simple as a North Pole–South Pole configuration. "Magnetic fields can be much more complicated and have additional poles, " explains Thomas Henning, Director at MPIA. "The fields can also change over time, which is part of a presumed explanation for the brightness variations of T Tauri stars."

Globaal genomen, this is an example of how observational techniques can drive progress in astronomy. In dit geval, the new observational techniques embody in GRAVITY were able to confirm ideas about the growth of young stellar objects that were proposed as long as 30 years ago. And future observations are set to help us understand even better how baby stars are being fed.

Soorten afvalwater

Soorten afvalwater Het produceren van kunstmest uit lucht zou vijf keer zo efficiënt kunnen zijn

Het produceren van kunstmest uit lucht zou vijf keer zo efficiënt kunnen zijn Microscoop op een chip kan medische expertise naar verre patiënten brengen

Microscoop op een chip kan medische expertise naar verre patiënten brengen Wetenschappers onderzoeken verouderde verf in microscopisch detail om de conserveringsinspanningen te informeren

Wetenschappers onderzoeken verouderde verf in microscopisch detail om de conserveringsinspanningen te informeren Kaliumjacht op eiwitfabrieken

Kaliumjacht op eiwitfabrieken

Planten die in de oceaan leven Habitat

Planten die in de oceaan leven Habitat Verwachte afname van het zee-ijs in de winter in het Noordpoolgebied gekoppeld aan de Euraziatische circulatie

Verwachte afname van het zee-ijs in de winter in het Noordpoolgebied gekoppeld aan de Euraziatische circulatie NASA's Aqua-satelliet ziet tropische depressie 01W eindigen in de buurt van Zuid-Vietnam

NASA's Aqua-satelliet ziet tropische depressie 01W eindigen in de buurt van Zuid-Vietnam Onderzoek toont de impact van ontbossing en bosverbranding op de biodiversiteit in de Amazone aan

Onderzoek toont de impact van ontbossing en bosverbranding op de biodiversiteit in de Amazone aan Het vaststellen van een tijdschaal voor 10 miljoen jaar geleden

Het vaststellen van een tijdschaal voor 10 miljoen jaar geleden

Hoofdlijnen

- De belangrijkste componenten van het skeletsysteem

- Interessante feiten over DNA-vingerafdrukken

- Een nieuwe regulator van de handel in blaasjes in planten

- Is eclips gelijk aan nacht in het plantenleven? Onderzoekers testen plantritmes tijdens zonsverduistering

- Luiheid heeft deze menselijke voorouder misschien verdoemd

- Soorten instrumenten die worden gebruikt voor het meten van lichaamstemperaturen

- Wat zijn de zes menselijke zintuigen?

- Woestijn in Zuid-Californië overspoeld met de beste superbloei in 20 jaar

- Waarom sommige mensen flauwvallen als ze bloed zien

- SpaceX SN8 om te lanceren en naar 60 te vliegen, volgende week 000 voet

- Nieuwe studie zaait twijfel over de samenstelling van 70 procent van ons universum

- Nieuw onderzoek suggereert explosieve vulkanische activiteit op Venus

- Melkweg heeft banden met buurman in galactische wapenwedloop

- Afbeelding:Noordpool van Enceladus

Voormalige kolenmijngemeenschappen zijn politiek meer ontgoocheld dan andere achtergebleven gebieden

Voormalige kolenmijngemeenschappen zijn politiek meer ontgoocheld dan andere achtergebleven gebieden Milieuwetenschappers nieuwe ozonisatiemethode behandelt water van antibioticaresiduen

Milieuwetenschappers nieuwe ozonisatiemethode behandelt water van antibioticaresiduen Zwaartekrachtgolfinzichten van internetstralende ballonnen

Zwaartekrachtgolfinzichten van internetstralende ballonnen Afvalwater behandelen met ozon kan geneesmiddelen omzetten in giftige stoffen

Afvalwater behandelen met ozon kan geneesmiddelen omzetten in giftige stoffen Wandelstranden, vrijwilligers verzamelen gegevens over dode zeevogels

Wandelstranden, vrijwilligers verzamelen gegevens over dode zeevogels Geen planeet B:tienduizenden doen mee aan wereldwijde jongerendemo voor klimaat

Geen planeet B:tienduizenden doen mee aan wereldwijde jongerendemo voor klimaat Test op halogeen

Test op halogeen  Hoe onze voedselkeuzes in bossen snijden en ons dichter bij virussen brengen

Hoe onze voedselkeuzes in bossen snijden en ons dichter bij virussen brengen

- Elektronica

- Biologie

- Zonsverduistering

- Wiskunde

- French | Italian | Spanish | Portuguese | Swedish | German | Dutch | Danish | Norway |

-

Wetenschap © https://nl.scienceaq.com