Wetenschap

Onderzoekers versnellen beeldvormingstechnieken voor het vastleggen van kleine moleculenstructuren

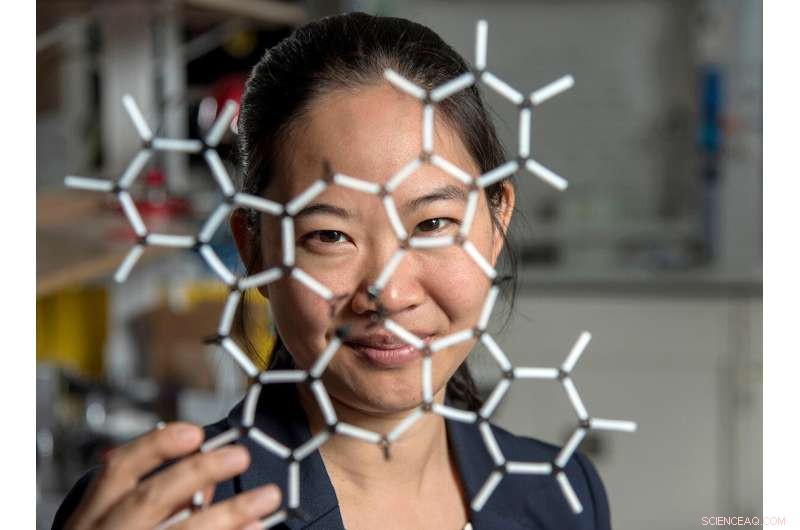

Pinshane Huang, uiterst links, sluit zich aan, Priti Kharel, tweede van links, Justin Bae en Patrick Carmichael, uiterst rechts, bij het Materials Research Laboratory. Afgebeeld op de tablet is Blanka Janicek. Credit:Heather Coit/The Grainger College of Engineering

Een onderzoeksinspanning van de University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign onder leiding van Pinshane Huang versnelt beeldvormingstechnieken om structuren van kleine moleculen duidelijk te visualiseren - een proces dat ooit voor onmogelijk werd gehouden. Hun ontdekking ontketent een eindeloos potentieel bij het verbeteren van toepassingen in het dagelijks leven, van plastic tot farmaceutica.

De universitair hoofddocent van het Department of Materials Science and Engineering werkt samen met co-lead auteurs Blanka Janicek, een '21 alumna en post-doc aan het Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in Berkeley, Californië, en Priti Kharel, een afgestudeerde student van het Department of Chemistry, om de methodologie te bewijzen waarmee onderzoekers kleine moleculaire structuren kunnen visualiseren en de huidige beeldvormingstechnieken kunnen versnellen.

Andere co-auteurs zijn onder meer afgestudeerde student Sang hyun Bae en studenten Patrick Carmichael en Amanda Loutris. Hun peer-reviewed onderzoek is onlangs gepubliceerd in Nano Letters .

De inspanningen van het team leggen de atomaire structuur van het molecuul bloot, waardoor onderzoekers kunnen begrijpen hoe het reageert, de chemische processen leren kennen en zien hoe de chemische verbindingen kunnen worden gesynthetiseerd.

"De structuur van een molecuul is zo fundamenteel voor zijn functie", zei Huang. "Wat we in ons werk hebben gedaan, is het mogelijk maken om die structuur direct te zien."

Het vermogen om de structuur van een klein molecuul te zien is van vitaal belang. Kharel deelt hoe belangrijk het is door het voorbeeld te geven van een medicijn dat bekend staat als thalidomide.

thalidomide, ontdekt in de jaren '60, werd voorgeschreven aan zwangere vrouwen om ochtendmisselijkheid te behandelen en bleek later ernstige geboorteafwijkingen of, in sommige gevallen, zelfs de dood te veroorzaken.

Wat ging er mis? Het medicijn had gemengde moleculaire structuren, waarvan de ene verantwoordelijk was voor de behandeling van ochtendmisselijkheid en de andere die helaas verwoestende, nadelige effecten op de foetus veroorzaakte.

De behoefte aan proactieve, niet reactieve wetenschap heeft Huang en haar studenten ertoe aangezet om deze onderzoeksinspanning voort te zetten die oorspronkelijk uit pure nieuwsgierigheid begon.

"Het is zo cruciaal om de structuren van deze moleculen nauwkeurig te bepalen," zei Kharel.

Meestal worden moleculaire structuren bepaald met indirecte technieken, een tijdrovende en moeilijke benadering die gebruik maakt van nucleaire magnetische resonantie of röntgendiffractie. Erger nog, indirecte methoden kunnen onjuiste structuren produceren die wetenschappers decennialang een verkeerd begrip geven van de samenstelling van een molecuul. The ambiguity surrounding small molecules' structures could be eliminated by using direct imaging methods.

In the last decade, Huang has seen significant advancements in cryogenic electron microscopy technology, where biologists freeze the large molecules to capture high-quality images of their structures.

"The question that I had was:What's keeping them from doing that same thing for small molecules?" Huang said. "If we could do that, you might be able to solve the structure (and) figure out how to synthesize a natural compound that a plant or animal makes. This could turn out to be really important, like a great disease-fighter," Huang said.

The challenge is that small molecules are often 100 or even 1,000 times smaller than large molecules, making their structures difficult to detect.

Determined, Huang's students began using existing large molecule methodology as a starting point for developing imaging techniques to make the small molecules' structures appear.

Unlike large molecules, the imaging signals from small molecules are easily overwhelmed by their surroundings. Instead of using ice, which typically serves as a layer of protection from the harsh environment of the electron microscope, the team devised another plan for keeping the small molecules' structures intact.

Pinshane Huang and her researchers discovered how to view structures in molecules, which opens a whole new realm of scientific possibilities. Credit:Heather Coit/The Grainger College of Engineering

How can you temper a molecule's environment? By using graphene.

Graphene, a single layer of carbon atoms that form a tight, hexagon-shaped honeycomb lattice, dissipates damaging reactions during imaging.

Stabilizing the small molecule's environment was only one issue the Illinois researchers had to manage. The team also had to limit its use of electrons, as low as one-millionth the number of electrons normally used, to illuminate the molecules.

Low doses of electrons ensure that the molecules are still moving enough for the researchers to capture an image.

"The way I like to think about it is the molecule doesn't like to be bombarded by higher-energy electrons, but we need to do that to be able to see the structure, and graphene helps dissipate some of that charge away from the molecule so that we can actually get a nice image of it," Janicek said.

Unfortunately, once captured, the molecules were nearly invisible in the image.

"When they take a low-dose image, it initially looks like noise or TV static—almost like nothing is there," Huang said.

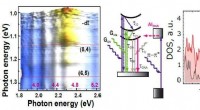

The trick was to isolate the atomic structures from that noise by using a Fourier transform—a mathematical function that breaks down the small molecule's image—to see its spatial frequency.

"We took images of hundreds of thousands of molecules and added them together to build a single, clear image," Kharel said.

This averaging approach allowed the team to create crisp images of the molecules' atoms without damaging the integrity of any individual molecule.

"Month after month, week after week, our resolution improved," Huang said. "And then one day, my students came in and showed me the individual carbon atoms—that's a major achievement. And of course, it comes after all this deep knowledge that they have gained to design an imaging experiment and how to unlock data from what looks like nothing."

This collective discovery is paving the way for many more structural molecule imaging findings.

"There's been this whole field of small molecules that have been left out in the cold, so to speak. We're shining a light on how do we get there as a field? How do we make this thing that for us right now is so hard?" Huang said. "One day it won't be—that's the hope."

The Illinois researchers' efforts are the first big step in turning that dream into reality.

"One day, this will be the way we solve the structure of a small molecule," Huang said. "People will simply throw the molecule in the electron microscope, take a picture and be done."

That dream inspires Huang and her Illinois team to keep the course.

"That's potentially life-changing, and we've made it exist," Huang said. "We haven't yet made it easy, but imaging techniques like this will change so much of science and technology." + Verder verkennen

ESR-STM op afzonderlijke moleculen en op moleculen gebaseerde structuren

Lab op een chip kan gezondheid monitoren, ziektekiemen en verontreinigende stoffen

Lab op een chip kan gezondheid monitoren, ziektekiemen en verontreinigende stoffen Droogijs versus Vloeibare stikstof

Droogijs versus Vloeibare stikstof  Hoe men één deeloplossing mengt met vier delen water

Hoe men één deeloplossing mengt met vier delen water  Studie gebruikt neutronen om licht te laten schijnen op het afsluiten van kankercellen

Studie gebruikt neutronen om licht te laten schijnen op het afsluiten van kankercellen Onderzoekers maken complexe molecule die spontaan vouwt als een eiwit

Onderzoekers maken complexe molecule die spontaan vouwt als een eiwit

EU-klimaatleiderschap in twijfel omdat blok het doel voor 2030 gaat missen

EU-klimaatleiderschap in twijfel omdat blok het doel voor 2030 gaat missen Geologen suggereren dat Horseshoe Abyssal Plain het begin kan zijn van een subductiezone

Geologen suggereren dat Horseshoe Abyssal Plain het begin kan zijn van een subductiezone NASA's volgen de grote orkaan Douglas in Hawaï

NASA's volgen de grote orkaan Douglas in Hawaï Wat nu nadat de financiering van 100 Resilient Cities is afgelopen?

Wat nu nadat de financiering van 100 Resilient Cities is afgelopen? Als u het raam in uw huis opent, worden de chemicaliën in de lucht niet weggespoeld

Als u het raam in uw huis opent, worden de chemicaliën in de lucht niet weggespoeld

Hoofdlijnen

- Genieten criminele psychopaten van de angst van andere mensen?

- De functies van de linker temporale kwab

- Wat maakt bodem, bodem? Onderzoekers vinden verborgen aanwijzingen in DNA

- Wasbloemen en hun complexe relatie

- Onderzoekers identificeren combinatie van factoren voor biologische cacaoopbrengst

- Studie van gierende kraanvogels onthult een band tussen paren zelfs voordat ze de paringsleeftijd hebben bereikt

- Hoe slapende listeria zich in cellen verbergt

- Japanse wetenschappers kweken medicijnen in kippeneieren

- Top 5 manieren om plezier te hebben in 2050

- Grafeen maakt kloksnelheden in het terahertz-bereik mogelijk

- Nieuw instrument houdt nanodeeltjes in de gaten

- Rode wijn kan de sleutel zijn tot draagbare technologie van de volgende generatie

- Onderzoekers ontwikkelen sondes op nanoschaal voor ssDNA-duurzaamheid onder UV-straling

- Volg het ... en ze zullen komen

Röntgenstralen onthullen chiraliteit in wervelende elektrische wervels

Röntgenstralen onthullen chiraliteit in wervelende elektrische wervels AI leren om te leren van niet-experts

AI leren om te leren van niet-experts Welke rol speelt chlorofyl in fotosynthese?

Welke rol speelt chlorofyl in fotosynthese?  Een storm met welke naam dan ook:het slaperige orkaanseizoen kan in september ontwaken

Een storm met welke naam dan ook:het slaperige orkaanseizoen kan in september ontwaken Onderzoekers ontwikkelen 3D-geprinte gelei

Onderzoekers ontwikkelen 3D-geprinte gelei Nieuwe ontdekking is veelbelovend voor het verminderen van bedreigingen voor klimaatverandering

Nieuwe ontdekking is veelbelovend voor het verminderen van bedreigingen voor klimaatverandering Archeologie kan ons helpen om van de geschiedenis te leren om een duurzame toekomst voor voedsel op te bouwen

Archeologie kan ons helpen om van de geschiedenis te leren om een duurzame toekomst voor voedsel op te bouwen Bangladesh heeft duizenden levens gered van een verwoestende cycloon - dit is hoe

Bangladesh heeft duizenden levens gered van een verwoestende cycloon - dit is hoe

- Elektronica

- Biologie

- Zonsverduistering

- Wiskunde

- French | Italian | Spanish | Portuguese | Swedish | German | Dutch | Danish | Norway |

-

Wetenschap © https://nl.scienceaq.com