Wetenschap

Natuurkunde Nobel-beloningen werken aan complexe systemen, zoals klimaat

Secretaris-generaal van de Koninklijke Zweedse Academie van Wetenschappen Goran Hansson, centrum, links geflankeerd door lid van het Nobelcomité voor Natuurkunde Thors Hans Hansson, links, en lid van het Nobelcomité voor Natuurkunde John Wettlaufer, Rechtsaf, maakt de winnaars bekend van de Nobelprijs voor Natuurkunde 2021 aan de Koninklijke Zweedse Academie van Wetenschappen, in Stockholm, Zweden, Dinsdag, 5 oktober 2021. De Nobelprijs voor natuurkunde is toegekend aan wetenschappers uit Japan, Duitsland en Italië. Syukuro Manabe en Klaus Hasselmann werden geciteerd voor hun werk in "de fysieke modellering van het klimaat op aarde, het kwantificeren van variabiliteit en het betrouwbaar voorspellen van de opwarming van de aarde". De tweede helft van de prijs werd toegekend aan Giorgio Parisi voor "de ontdekking van het samenspel van wanorde en fluctuaties in fysieke systemen van atomaire tot planetaire schalen." Credit:Pontus Lundahl/TT via AP

Drie wetenschappers wonnen dinsdag de Nobelprijs voor natuurkunde voor werk dat orde vond in schijnbare wanorde. helpen bij het verklaren en voorspellen van complexe natuurkrachten, inclusief het vergroten van ons begrip van klimaatverandering.

Syukuro Manabe, oorspronkelijk uit Japan, en Klaus Hasselmann uit Duitsland werden geciteerd voor hun werk bij het ontwikkelen van voorspellingsmodellen van het klimaat op aarde en 'het betrouwbaar voorspellen van de opwarming van de aarde'. De tweede helft van de prijs ging naar Giorgio Parisi uit Italië voor het verklaren van stoornissen in fysieke systemen, variërend van die zo klein als de binnenkant van atomen tot de grootte van een planeet.

Hasselmann vertelde The Associated Press dat hij "liever geen opwarming van de aarde en geen Nobelprijs had."

Manabe zei dat het uitzoeken van de fysica achter klimaatverandering "1, 000 keer" gemakkelijker dan de wereld er iets aan te laten doen. Hij zei dat de fijne kneepjes van het beleid en de samenleving veel moeilijker te doorgronden zijn dan de complexiteit van kooldioxide in wisselwerking met de atmosfeer, die vervolgens de omstandigheden in de oceaan en op het land verandert, die vervolgens de lucht weer verandert in een constante cyclus.

Hij noemde klimaatverandering 'een grote crisis'.

De prijs komt minder dan vier weken voor de start van klimaatonderhandelingen op hoog niveau in Glasgow, Schotland, waar wereldleiders zal worden gevraagd hun toezeggingen op te voeren om de opwarming van de aarde te beteugelen.

De Nobel-winnende wetenschappers gebruikten hun moment in de schijnwerpers om aan te dringen op actie.

"Het is zeer dringend dat we zeer krachtige beslissingen nemen en in een zeer hoog tempo doorgaan" bij het aanpakken van de opwarming van de aarde, zei Parisi. Hij deed de oproep, ook al was zijn deel van de prijs voor werk op een ander gebied van de natuurkunde.

Alle drie de wetenschappers werken aan wat bekend staat als "complexe systemen, " waarvan klimaat maar één voorbeeld is. Maar de prijs ging naar twee vakgebieden die in veel opzichten tegengesteld zijn, hoewel ze het doel delen om betekenis te geven aan wat willekeurig en chaotisch lijkt, zodat het kan worden voorspeld.

Parisi's onderzoek concentreert zich grotendeels op subatomaire deeltjes, voorspellen hoe ze zich op schijnbaar chaotische manieren bewegen en waarom, en is enigszins esoterisch, terwijl het werk van Manabe en Hasselmann gaat over grootschalige mondiale krachten die ons dagelijks leven vormgeven.

-

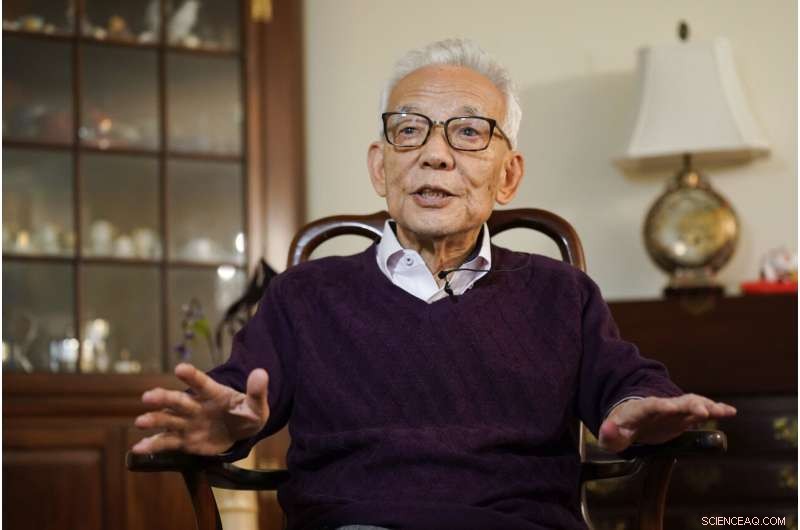

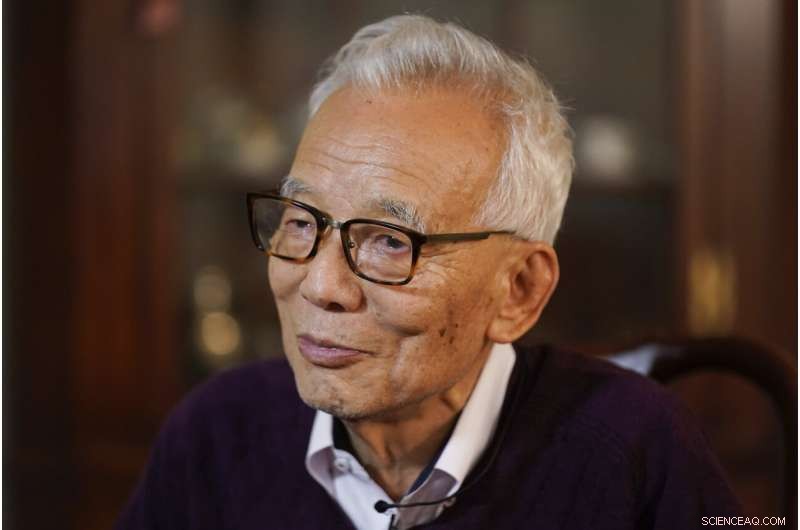

Syukuro Manabe, Rechtsaf, spreekt met verslaggevers in zijn huis in Princeton, NJ, Dinsdag, 5 oktober 2021. Manabe en twee andere wetenschappers hebben de Nobelprijs voor natuurkunde gewonnen voor werk dat orde vond in schijnbare wanorde, helpen bij het verklaren en voorspellen van complexe natuurkrachten, inclusief het vergroten van ons begrip van klimaatverandering. Krediet:AP Photo/Seth Wenig

-

Italiaanse theoretisch natuurkundige Giorgio Parisi, centrum, poseert voor een selfie foto met zijn collega's in de Accademia dei Lincei, Dinsdag, 5 oktober 2021, in Rome, na de toekenning van de Nobelprijs voor Natuurkunde 2021, samen met Syukuro Manabe en Klaus Hasselmann, door de Koninklijke Zweedse Academie van Wetenschappen in Stockholm. Krediet:AP Photo/Domenico Stinellis

De rechters zeiden Manabe, 90, en Hasselmann, 89, "legde de basis van onze kennis van het klimaat op aarde en hoe menselijke acties het beïnvloeden."

Vanaf de jaren 60, Manabe, nu gevestigd aan de Princeton University, creëerden de eerste klimaatmodellen die voorspelden wat er zou gebeuren als kooldioxide zich ophoopte in de atmosfeer.

Decennialang hadden wetenschappers aangetoond dat koolstofdioxide warmte vasthoudt, maar het werk van Manabe bood bijzonderheden. Het stelde wetenschappers in staat om uiteindelijk te laten zien hoe de klimaatverandering zal verergeren en hoe snel, afhankelijk van hoeveel koolstofvervuiling wordt uitgespuwd.

Manabe is zo'n pionier dat andere klimaatwetenschappers zijn paper uit 1967 met wijlen Richard Wetherald "de meest invloedrijke klimaatpaper ooit, " zei NASA-hoofd klimaatmodeller Gavin Schmidt. Manabe's Princeton-collega Tom Delworth noemde Manabe "de Michael Jordan van het klimaat."

Giorgio Parisi poseert voor foto's in Rome, Dinsdag, 5 oktober 2021. De Nobelprijs voor natuurkunde is toegekend aan wetenschappers uit Japan, Duitsland en Italië. Syukuro Manabe en Klaus Hasselmann werden geciteerd voor hun werk in "de fysieke modellering van het klimaat op aarde, het kwantificeren van variabiliteit en het betrouwbaar voorspellen van de opwarming van de aarde". De tweede helft van de prijs werd toegekend aan Giorgio Parisi voor "de ontdekking van het samenspel van wanorde en fluctuaties in fysieke systemen van atomaire tot planetaire schalen." Credit:Cecilia Fabiano/LaPresse via AP

"Suki heeft de weg geëffend voor de hedendaagse klimaatwetenschap, niet alleen het gereedschap, maar ook hoe het te gebruiken, " zei collega-klimaatwetenschapper Gabriel Vecchi van Princeton. "Ik kan de keren niet tellen dat ik dacht dat ik met iets nieuws kwam, en het staat in een van zijn papieren."

Manabe's modellen van 50 jaar geleden "voorspelden nauwkeurig de opwarming die daadwerkelijk plaatsvond in de volgende decennia, " zei klimaatwetenschapper Zeke Hausfather van het Breakthrough Institute. Het werk van Manabe dient "als een waarschuwing voor ons allemaal dat we hun projecties van een veel warmere toekomst moeten nemen als we koolstofdioxide vrij serieus blijven uitstoten."

"Ik had nooit gedacht dat dit ding dat ik zou gaan bestuderen zo'n enorme consequentie zou hebben, "Zei Manabe op een persconferentie in Princeton. "Ik deed het gewoon uit nieuwsgierigheid."

Ongeveer een decennium na het eerste werk van Manabe, Hasselmann, van het Max Planck Instituut voor Meteorologie in Hamburg, Duitsland, hielp verklaren waarom klimaatmodellen betrouwbaar kunnen zijn ondanks de schijnbaar chaotische aard van het weer. Hij ontwikkelde ook manieren om te zoeken naar specifieke tekenen van menselijke invloed op het klimaat.

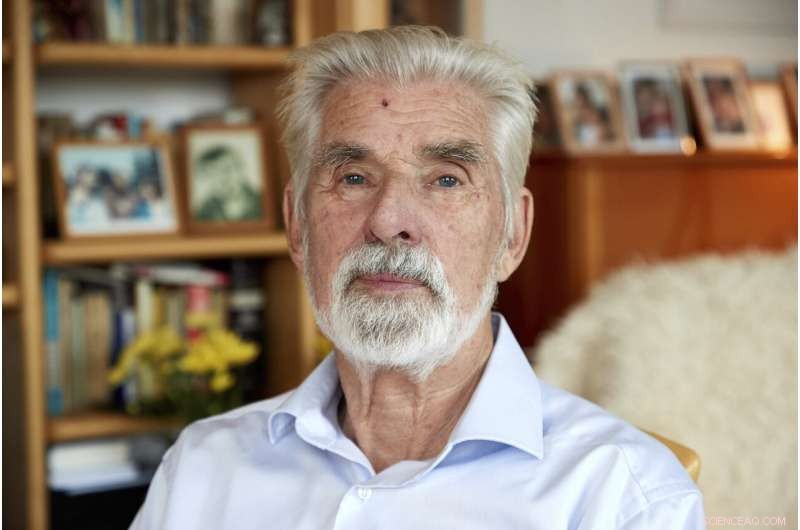

Klimaatonderzoeker Klaus Hasselmann staat op het balkon van zijn appartement in Hamburg, Duitsland, Dinsdag, 5 oktober 2021. De Nobelprijs voor Natuurkunde gaat dit jaar naar de Duitser Klaus Hasselmann, Syukuro Manabe (VS) en de Italiaan Giorgio Parisi voor fysieke modellen van het klimaat op aarde. Krediet:Georg Wendt/dpa via AP

In de tussentijd, Parijs, van de Sapienza Universiteit van Rome, "bouwde een diep fysiek en wiskundig model" dat het mogelijk maakte om complexe systemen te begrijpen op gebieden die zo verschillend zijn als wiskunde, biologie, neurowetenschap en machine learning.

Zijn werk was oorspronkelijk gericht op het zogenaamde spinglas, een soort metaallegering waarvan het gedrag wetenschappers lang verbijsterd heeft. Parijs, 73, ontdekte verborgen patronen die de manier waarop het handelde verklaarden, het creëren van theorieën die kunnen worden toegepast op andere onderzoeksgebieden, te.

Alle drie de natuurkundigen gebruikten complexe wiskunde om te verklaren en te voorspellen wat leek op chaotische natuurkrachten. Dat heet modelleren.

"Op fysica gebaseerde klimaatmodellen maakten het mogelijk om de hoeveelheid en het tempo van de opwarming van de aarde te voorspellen, inclusief enkele van de gevolgen zoals stijgende zeeën, toegenomen extreme regenval en sterkere orkanen, decennia voordat ze konden worden waargenomen, " zei de Duitse klimaatwetenschapper en modelleur Stefan Rahmstorf. Hij noemde Hasselmann en Manabe pioniers op dit gebied.

De Italiaanse theoretisch natuurkundige Giorgio Parisi spreekt met journalisten als hij aankomt bij de Accademia dei Lincei, Dinsdag, 5 oktober 2021, in Rome, na de toekenning van de Nobelprijs voor Natuurkunde 2021, samen met Syukuro Manabe en Klaus Hasselmann, door de Koninklijke Zweedse Academie van Wetenschappen in Stockholm. Krediet:AP Photo / Domenico Stinellis

Toen klimaatwetenschappers met het Intergouvernementeel Panel over klimaatverandering van de Verenigde Naties en de voormalige Amerikaanse vice-president Al Gore in 2007 de Nobelprijs voor de Vrede wonnen, sommigen die de opwarming van de aarde ontkennen, verwierpen het als een politieke zet. Misschien anticiperend op controverse, leden van de Zweedse Academie van Wetenschappen, die de Nobelprijs toekent, benadrukte dat dinsdag een wetenschapsprijs was.

"Wat we zeggen is dat de modellering van het klimaat stevig gebaseerd is op fysische theorie en bekende fysica, ' zei de Zweedse natuurkundige Thors Hans Hansson bij de aankondiging.

Voor een wetenschapper die handelt in voorspellingen, Hasselmann zei dat de prijs hem overrompelde.

"Ik was nogal verrast toen ze belden, "zei hij. "Ik bedoel, dit is iets wat ik vele jaren geleden heb gedaan."

Maar Parisi zei:"Ik wist dat er een niet te verwaarlozen mogelijkheid" was om te winnen.

-

Syukuro Manabe spreekt met verslaggevers in zijn huis in Princeton, NJ, Dinsdag, 5 oktober 2021. Manabe en twee andere wetenschappers hebben de Nobelprijs voor natuurkunde gewonnen voor werk dat orde vond in schijnbare wanorde, helpen bij het verklaren en voorspellen van complexe natuurkrachten, inclusief het vergroten van ons begrip van klimaatverandering. Krediet:AP Photo/Seth Wenig

-

De Italiaanse theoretisch natuurkundige Giorgio Parisi spreekt met journalisten als hij aankomt bij de Accademia dei Lincei, Dinsdag, 5 oktober 2021, in Rome, na de toekenning van de Nobelprijs voor Natuurkunde 2021, samen met Syukuro Manabe en Klaus Hasselmann, door de Koninklijke Zweedse Academie van Wetenschappen in Stockholm. Krediet:AP Photo/Domenico Stinellis

-

Syukuro Manabe spreekt met verslaggevers in zijn huis in Princeton, NJ, Dinsdag, 5 oktober 2021. Manabe en twee andere wetenschappers hebben de Nobelprijs voor natuurkunde gewonnen voor werk dat orde vond in schijnbare wanorde, helpen bij het verklaren en voorspellen van complexe natuurkrachten, inclusief het vergroten van ons begrip van klimaatverandering. Krediet:AP Photo/Seth Wenig

-

Klimaatonderzoeker Klaus Hasselmann zit in zijn appartement in Hamburg, Duitsland, Dinsdag, 5 oktober 2021. De Nobelprijs voor Natuurkunde gaat dit jaar naar de Duitser Klaus Hasselmann, Syukuro Manabe (VS) en de Italiaan Giorgio Parisi voor fysieke modellen van het klimaat op aarde. Krediet:Georg Wendt/dpa via AP

-

Italiaanse wetenschapper Giorgio Parisi gebruikt zijn telefoon op het balkon van zijn huis in Rome, Dinsdag, 5 oktober 2021. De Nobelprijs voor natuurkunde is toegekend aan wetenschappers uit Japan, Duitsland en Italië. Syukuro Manabe en Klaus Hasselmann werden geciteerd voor hun werk in "de fysieke modellering van het klimaat op aarde, het kwantificeren van variabiliteit en het betrouwbaar voorspellen van de opwarming van de aarde". De tweede helft van de prijs werd toegekend aan Giorgio Parisi voor "de ontdekking van het samenspel van wanorde en fluctuaties in fysieke systemen van atomaire tot planetaire schalen." Credit:AP Photo/Alessandra Tarantino

-

Giorgio Parisi, centrum, opent een fles mousserende wijn aan de wetenschappelijke instelling Accademia dei Lincei in Rome, Dinsdag, 5 oktober 2021. De Nobelprijs voor natuurkunde is toegekend aan wetenschappers uit Japan, Duitsland en Italië. Syukuro Manabe en Klaus Hasselmann werden geciteerd voor hun werk in "de fysieke modellering van het klimaat op aarde, het kwantificeren van variabiliteit en het betrouwbaar voorspellen van de opwarming van de aarde". De tweede helft van de prijs werd toegekend aan Giorgio Parisi voor "de ontdekking van het samenspel van wanorde en fluctuaties in fysieke systemen van atomaire tot planetaire schalen." Credit:Cecilia Fabiano/LaPresse via AP

-

Italiaanse theoretisch natuurkundige Giorgio Parisi, Rechtsaf, telefoontjes krijgt van collega Massimo Inguscio, voorzitter van de Italiaanse Nationale Onderzoeksraad, als hij aankomt bij de Accademia dei Lincei, Dinsdag, 5 oktober 2021, in Rome, na de toekenning van de Nobelprijs voor Natuurkunde 2021, samen met Syukuro Manabe en Klaus Hasselmann, door de Koninklijke Zweedse Academie van Wetenschappen in Stockholm. Krediet:AP Photo / Domenico Stinellis

-

Voetgangers nemen kopieën van een extra editie van de Yomiuri-krant, waarin wordt gemeld dat wetenschapper Syukuro Manabe de Nobelprijs voor natuurkunde 2021 heeft gekregen in Tokio, Dinsdag, 5 oktober 2021. Krediet:AP Photo/Koji Sasahara

De prijs wordt geleverd met een gouden medaille en 10 miljoen Zweedse kronen (meer dan $ 1,14 miljoen). Het geld komt van een legaat dat is achtergelaten door de maker van de prijs, Zweedse uitvinder Alfred Nobel, die in 1895 stierf.

Op maandag, de Nobelprijs voor de geneeskunde werd toegekend aan de Amerikanen David Julius en Ardem Patapoutian voor hun ontdekkingen over hoe het menselijk lichaam temperatuur en aanraking waarneemt.

De komende dagen worden prijzen uitgereikt op het gebied van scheikunde, literatuur, vrede en economie.

******

Persbericht Nobelcomité:De Nobelprijs voor de Natuurkunde 2021

De Koninklijke Zweedse Academie van Wetenschappen heeft besloten de Nobelprijs voor Natuurkunde 2021 toe te kennen

"voor baanbrekende bijdragen aan ons begrip van complexe fysieke systemen"

met de ene helft gezamenlijk aan

Syukuro Manabe

Princeton Universiteit, VS

Klaus Hasselmann

Max Planck Instituut voor Meteorologie, Hamburg, Duitsland

"voor de fysieke modellering van het klimaat op aarde, het kwantificeren van variabiliteit en het betrouwbaar voorspellen van de opwarming van de aarde"

en de andere helft om

Giorgio Parisi

Sapienza-universiteit van Rome, Italië

"voor de ontdekking van het samenspel van wanorde en fluctuaties in fysieke systemen van atomaire tot planetaire schalen"

Natuurkunde voor klimaat en andere complexe fenomenen

Drie laureaten delen dit jaar de Nobelprijs voor natuurkunde voor hun onderzoek naar chaotische en schijnbaar willekeurige verschijnselen. Syukuro Manabe en Klaus Hasselmann hebben de basis gelegd voor onze kennis van het klimaat op aarde en hoe de mensheid dit beïnvloedt. Giorgio Parisi wordt beloond voor zijn revolutionaire bijdragen aan de theorie van ongeordende materialen en willekeurige processen.

Complexe systemen worden gekenmerkt door willekeur en wanorde en zijn moeilijk te begrijpen. This year's Prize recognises new methods for describing them and predicting their long-term behaviour.

One complex system of vital importance to humankind is Earth's climate. Syukuro Manabe demonstrated how increased levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere lead to increased temperatures at the surface of the Earth. In de jaren 1960, he led the development of physical models of the Earth's climate and was the first person to explore the interaction between radiation balance and the vertical transport of air masses. His work laid the foundation for the development of current climate models.

About ten years later, Klaus Hasselmann created a model that links together weather and climate, thus answering the question of why climate models can be reliable despite weather being changeable and chaotic. He also developed methods for identifying specific signals, fingerprints, that both natural phenomena and human activities imprint in he climate. His methods have been used to prove that the increased temperature in the atmosphere is due to human emissions of carbon dioxide.

Around 1980, Giorgio Parisi discovered hidden patterns in disordered complex materials. His discoveries are among the most important contributions to the theory of complex systems. They make it possible to understand and describe many different and apparently entirely random materials and phenomena, not only in physics but also in other, very different areas, such as mathematics, biologie, neuroscience and machine learning.

"The discoveries being recognised this year demonstrate that our knowledge about the climate rests on a solid scientific foundation, based on a rigorous analysis of observations. This year's Laureates have all contributed to us gaining deeper insight into the properties and evolution of complex physical systems, " says Thors Hans Hansson, chair of the Nobel Committee for Physics.

Popular information

They found hidden patterns in the climate and in other complex phenomena

Three Laureates share this year's Nobel Prize in Physics for their studies of complex phenomena. Syukuro Manabe and Klaus Hasselmann laid the foundation of our knowledge of the Earth's climate and how humanity influences it. Giorgio Parisi is rewarded for his revolutionary contributions to the theory of disordered and random phenomena.

All complex systems consist of many different inter-acting parts. They have been studied by physicists for a couple of centuries, and can be difficult to describe mathematically – they may have an enormous number of components or be governed by chance. They could also be chaotic, like the weather, where small deviations in initial values result in huge differences at a later stage. This year's Laureates have all contributed to us gaining greater knowledge of such systems and their long-term development.

The Earth's climate is one of many examples of complex systems. Manabe and Hasselmann are awarded the Nobel Prize for their pioneering work on developing climate models. Parisi is rewarded for his theoretical solutions to a vast array of problems in the theory of complex systems.

Syukuro Manabe demonstrated how increased concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere lead to increased temperatures at the surface of the Earth. In de jaren 1960, he led the development of physical models of the Earth's climate and was the first person to explore the interaction between radiation balance and the vertical transport of air masses. His work laid the foundation for the development of climate models.

About ten years later, Klaus Hasselmann created a model that links together weather and climate, thus answering the question of why climate models can be reliable despite weather being changeable and chaotic. He also developed methods for identifying specific signals, fingerprints, that both natural phenomena and human activities imprint in the climate. His methods have been used to prove that the increased temperature in the atmosphere is due to human emissions of carbon dioxide.

Around 1980, Giorgio Parisi discovered hidden patterns in disordered complex materials. His discoveries are among the most important contributions to the theory of complex systems. They make it possible to understand and describe many different and apparently entirely random complex materials and phenomena, not only in physics but also in other, very different areas, such as mathematics, biologie, neuroscience and machine learning.

The greenhouse effect is vital to life

Two hundred years ago, French physicist Joseph Fourier studied the energy balance between the sun's radiation towards the ground and the radiation from the ground. He understood the atmosphere's role in this balance; at the Earth's surface, the incoming solar radiation is transformed into outgoing radiation – "dark heat" – which is absorbed by the atmosphere, thus heating it. The atmosphere's protective role is now called the greenhouse effect. This name comes from its similarity to the glass panes of a greenhouse, which allow through the heating rays of the sun, but trap the heat inside. Echter, the radiative processes in the atmosphere are far more complicated.

The task remains the same as that undertaken by Fourier – to investigate the balance between the shortwave solar radiation coming towards our planet and Earth's outgoing longwave, infrared radiation. The details were added by many climate scientists over the following two centuries. Contemporary climate models are incredibly powerful tools, not only for understanding the climate, but also for understanding the global heating for which humans are responsible.

These models are based on the laws of physics and have been developed from models that were used to predict the weather. Weather is described by meteorological quantities such as temperature, precipitation, wind or clouds, and is affected by what happens in the oceans and on land. Climate models are based upon the weather's calculated statistical properties, such as average values, standard deviations, highest and lowest measured values, etcetera. They cannot tell us what the weather will be in Stockholm on 10 December next year, but we can get some idea of what temperature or how much rainfall we can expect on average in Stockholm in December.

Establishing the role of carbon dioxide

The greenhouse effect is essential for life on Earth. It governs temperature because the greenhouse gases in the atmosphere – carbon dioxide, methane, water vapour and other gases – first absorb the Earth's infrared radiation and then release this absorbed energy, heating up the surrounding air and the ground below it.

Greenhouse gases actually comprise a very small proportion of the Earth's dry atmosphere, which is largely nitrogen and oxygen – these are 99 per cent by volume. Carbon dioxide is just 0.04 per cent by volume. The most powerful greenhouse gas is water vapour, but we cannot control the concentration of water vapour in the atmosphere, while we can control that of carbon dioxide.

The amount of water vapour in the atmosphere is highly dependent on temperature, leading to a feed-back mechanism. More carbon dioxide in the atmosphere makes it warmer, allowing more water vapour to be held in the air, which increases the greenhouse effect and makes temperatures rise even further. If the carbon dioxide level drops, some of the water vapour will condense and the temperature will fall.

An important first piece of the puzzle about the impact of carbon dioxide came from Swedish researcher and Nobel Laureate Svante Arrhenius. Incidentally, it was his colleague, meteorologist Nils Ekholm who, in 1901, was the first to use the word greenhouse in describing the atmosphere's storage and re-radiation of heat.

Arrhenius understood the physics responsible for the greenhouse effect by the end of the 19th century – that outgoing radiation is proportional to the radiant body's absolute temperature (T) to the power of four (T⁴). The hotter the source of the radiation, the shorter the rays' wavelength. The Sun has a surface temperature of 6, 000°C and primarily emits rays in the visible spectrum. Earth, with a surface temperature of just 15°C, re-radiates infrared radiation that is invisible to us. If the atmosphere did not absorb this radiation, the surface temperature would barely exceed –18°C.

Arrhenius was actually attempting to work out what caused the recently discovered phenomenon of ice ages. He arrived at the conclusion that if the level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere halved, this would be enough for the Earth to enter a new ice age. And vice versa – a doubling of the amount of carbon dioxide would increase the temperature by 5–6°C, a result which, somewhat fortuitously, is astoundingly close to current estimates.

Pioneering model for the effect of carbon dioxide

In de jaren vijftig, Japanese atmospheric physicist Syukuro Manabe was one of the young and talented researchers in Tokyo who left Japan, which had been devastated by war, and continued their careers in the US. The aim of Manabes's research, like that of Arrhenius around seventy years earlier, was to understand how increased levels of carbon dioxide can cause increased temperatures. Echter, while Arrhenius had focused on radiation balance, in the 1960s Manabe led work on the development of physical models to incorporate the vertical transport of air masses due to convection, as well as the latent heat of water vapour.

To make these calculations manageable, he chose to reduce the model to one dimension – a vertical column, 40 kilometres up into the atmosphere. Toch, it took hundreds of valuable computing hours to test the model by varying the levels of gases in the atmosphere. Oxygen and nitrogen had negligible effects on surface temperature, while carbon dioxide had a clear impact:when the level of carbon dioxide doubled, global temperature increased by over 2°C.

The model confirmed that this heating really was due to the increase in carbon dioxide, because it predicted rising temperatures closer to the ground while the upper atmosphere got colder. If variations in solar radiation were responsible for the increase in temperature instead, the entire atmosphere should have been heating at the same time.

Sixty years ago, computers were hundreds of thousands of times slower than they are now, so this model was relatively simple, but Manabe got the key features right. You must always simplify, hij zegt. You cannot compete with the complexity of nature – there is so much physics involved in every raindrop that it would never be possible to compute absolutely everything. The insights from the onedimensional model led to a climate model in three dimensions, which Manabe published in 1975; this was yet another milestone on the road to understanding the climate's secrets.

Weather is chaotic

About ten years after Manabe, Klaus Hasselmann succeeded in linking together weather and climate by finding a way to outsmart the rapid and chaotic weather changes that were so troublesome for calculations. Our planet has vast shifts in its weather because solar radiation is so unevenly distributed, both geographically and over time. Earth is round, so fewer of the sun's rays reach the higher latitudes than the lower ones around the Equator. Not only this, but the Earth's axis is tilted, producing seasonal differences in incoming radiation. The differences in density between warmer and colder air cause the colossal transports of heat between different latitudes, between ocean and land, between higher and lower air masses, which drive the weather on our planet.

Zoals we allemaal weten, making reliable predictions about the weather for more than the next ten days is a challenge. Two hundred years ago, the renowned French scientist, Pierre-Simon de Laplace, stated that if we just knew the position and speed of all the particles in the universe, it should be possible to both calculate what has happened and what will happen in our world. In principe, this should be true; Newton's three-century old laws of motion, which also describe air transport in the atmosphere, are entirely deterministic – they are not governed by chance.

Echter, nothing could be more wrong when it comes to the weather. This is partly because, in praktijk, it is impossible to be precise enough – to state the air temperature, druk, humidity or wind conditions for every point in the atmosphere. Also, the equations are nonlinear; small deviations in initial values can make a weather system evolve in entirely different ways. Based on the question of whether a butterfly flapping its wings in Brazil could cause a tornado in Texas, the phenomenon was named the butterfly effect. In praktijk, this means that it is impossible to produce long-term weather forecasts – the weather is chaotic; this discovery was made in the 1960s by the American meteorologist Edward Lorenz, who laid the foundation of today's chaos theory.

Making sense of noisy data

How can we produce reliable climate models for several decades or hundreds of years into the future, despite weather being a classic example of a chaotic system? Around 1980, Klaus Hasselmann demonstrated how chaotically changing weather phenomena can be described as rapidly changing noise, thus placing long-term climate forecasts on a firm scientific foundation. Verder, he developed methods for identifying human impact on the observed global temperature.

As a young doctoral student in physics in Hamburg, Duitsland, in the 1950s, Hasselmann worked on fluid dynamics, then began to develop observations and theoretical models for ocean waves and currents. He moved to California and continued with oceanography, meeting colleagues such as Charles David Keeling, with whom the Hasselmanns started a madrigal choir. Keeling is legendary for beginning, back in 1958, what is now the longest series of atmospheric carbon dioxide measurements at the Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii. Little did Hasselmann know that in his later work he would regularly use the Keeling Curve, which shows changes in the carbon dioxide levels.

Obtaining a climate model from noisy weather data can be illustrated by walking a dog:the dog runs off the lead, backwards and forwards, side to side and around your legs. How can you use the dog's tracks to see whether you are walking or standing still? Or whether you are walking quickly or slowly? The dog's tracks are the changes in the weather, and your walk is the calculated climate. Is it even possible to draw conclusions about long-term trends in the climate using chaotic and noisy weather data?

One additional difficulty is that the fluctuations that influence the climate are extremely variable over time – they may be rapid, such as in wind strength or air temperature, or very slow, such as melting ice sheets and warming oceans. Bijvoorbeeld, uniform heating by just one degree can take a thousand years for the ocean, but just a few weeks for the atmosphere. The decisive trick was incorporating the rapid changes in the weather into the calculations as noise, and showing how this noise affects the climate.

Hasselmann created a stochastic climate model, which means that chance is built into the model. His inspiration came from Albert Einstein's theory of Brownian motion, also called a random walk. Using this theory, Hasselmann demonstrated that the rapidly changing atmosphere can actually cause slow variations in the ocean.

Discerning traces of human impact

Once the model for climate variations was finished, Hasselmann developed methods for identifying human impact on the climate system. He found that the models, along with observations and theoretical considerations, contain adequate information about the properties of noise and signals. Bijvoorbeeld, changes in solar radiation, volcanic particles or levels of greenhouse gases leave unique signals, fingerprints, which can be separated out. This method for identifying fingerprints can also be applied to the effect that humans have on the climate system. Hasselman thus cleared the way to further studies of climate change, which have demonstrated traces of human impact on the climate using a large number of independent observations.

Climate models have become increasingly refined as the processes included in the climate's complicated interactions are mapped more thoroughly, not least through satellite measurements and weather observations. The models clearly show an accelerating greenhouse effect; since the mid-19th century, the levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere have increased by 40 per cent. Earth's atmosphere has not contained this much carbon dioxide for hundreds of thousands of years. Overeenkomstig, temperature measurements show that the world has heated by 1°C over the past 150 years.

Syukuro Manabe and Klaus Hasselmann have contributed to the greatest benefit for humankind, in the spirit of Alfred Nobel, by providing a solid physical foundation for our knowledge of Earth's climate. We can no longer say that we did not know – the climate models are unequivocal. Is Earth heating up? Ja. Is the cause the increased amounts of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere? Ja. Can this be explained solely by natural factors? No. Are humanity's emissions the reason for the increasing temperature? Ja.

Methods for disordered systems

Around 1980, Giorgio Parisi presented his discoveries about how apparently random phenomena are governed by hidden rules. His work is now considered to be among the most important contributions to the theory of complex systems.

Modern studies of complex systems are rooted in the statistical mechanics developed in the second half of the 19th century by James C. Maxwell, Ludwig Boltzmann and J. Willard Gibbs, who named this field in 1884. Statistical mechanics evolved from the insight that a new type of method was necessary for describing systems, such as gases or liquids, that consist of large numbers of particles. This method had to take the particles' random movements into account, so the basic idea was to calculate the particles' average effect instead of studying each particle individually. Bijvoorbeeld, the temperature in a gas is a measure of the average value of the energy of the gas particles. Statistical mechanics is a great success, because it provides a microscopic explanation for macroscopic properties in gases and liquids, such as temperature and pressure.

The particles in a gas can be regarded as tiny balls, flying around at speeds that increase with higher temperatures. When the temperature drops, or pressure increases, the balls first condense into a liquid and then into a solid. This solid is often a crystal, where the balls are organised in a regular pattern. Echter, if this change happens rapidly, the balls may form an irregular pattern that does not change even if the liquid is further cooled or squeezed together. If the experiment is repeated, the balls will assume a new pattern, despite the change happening in exactly the same way. Why are the results different?

Understanding complexity

These compressed balls are a simple model for ordinary glass and for granular materials, such as sand or gravel. Echter, the subject of Parisi's original work was a different kind of system – spin glass. This is a special type of metal alloy in which iron atoms, bijvoorbeeld, are randomly mixed into a grid of copper atoms. Even though there are only a few iron atoms, they change the material's magnetic properties in a radical and very puzzling manner. Each iron atom behaves like a small magnet, of draaien, which is affected by the other iron atoms close to it. In an ordinary magnet, all the spins point in the same direction, but in a spin glass they are frustrated; some spin pairs want to point in the same direction and others in the opposite direction – so how do they find an optimal orientation?

In the introduction to his book about spin glass, Parisi writes that studying spin glass is like watching the human tragedies of Shakespeare's plays. If you want to make friends with two people at the same time, but they hate each other, it can be frustrating. This is even more the case in a classical tragedy, where strongly emotional friends and enemies meet on stage. How can the tension in the room be minimised?

Spin glasses and their exotic properties provide a model for complex systems. In de jaren zeventig, many physicists, including several Nobel Laureates, searched for a way to describe the mysterious and frustrating spin glasses. One method they used was the replica trick, a mathematical technique in which many copies, replicas, of the system are processed at the same time. Echter, in terms of physics, the results of the original calculations were unfeasible.

1979, Parisi made a decisive breakthrough when he demonstrated how the replica trick could be ingeniously used to solve a spin glass problem. He discovered a hidden structure in the replicas, and found a way to describe it mathematically. It took many years for Parisi's solution to be proven mathematically correct. Vanaf dat moment, his method has been used in many disordered systems and become a cornerstone of the theory of complex systems.

The fruits of frustration are many and varied Both spin glass and granular materials are examples of frustrated systems, in which various constituents must arrange themselves in a manner that is a compromise between counteracting forces. The question is how they behave and what the results are. Parisi is a master at answering these questions for many different materials and phenomena. His fundamental discoveries about the structure of spin glasses were so deep that they not only influenced physics, but also mathematics, biologie, neuroscience and machine learning, because all these fields include problems that are directly related to frustration.

Parisi has also studied many other phenomena in which random processes play a decisive role in how structures are created and how they develop, and dealt with questions such as:Why do we have periodically recurring ice ages? Is there a more general mathematical description of chaos and turbulent systems? Or – how do patterns arise in a murmuration of thousands of starlings? This question may seem far removed from spin glass. Echter, Parisi has said that most of his research has dealt with how simple behaviours give rise to complex collective behaviours, and this applies to both spin glasses and starlings.

Advanced information:www.nobelprize.org/prizes/phys … dvanced-information/

© 2021 The Associated Press. Alle rechten voorbehouden. Dit materiaal mag niet worden gepubliceerd, uitzending, herschreven of gedistribueerd zonder toestemming.

Een voordelige aerogel op basis van legeringen als elektrokatalysator voor koolstoffixatie

Een voordelige aerogel op basis van legeringen als elektrokatalysator voor koolstoffixatie Cheminformatics-benaderingen voor het maken van nieuwe haarkleurmiddelen

Cheminformatics-benaderingen voor het maken van nieuwe haarkleurmiddelen Ontdekking van bacteriële enzymactiviteit kan leiden tot nieuwe op suiker gebaseerde medicijnen

Ontdekking van bacteriële enzymactiviteit kan leiden tot nieuwe op suiker gebaseerde medicijnen Dansende materie:nieuwe vorm van beweging van cyclische macromoleculen ontdekt

Dansende materie:nieuwe vorm van beweging van cyclische macromoleculen ontdekt Hoe een geïsoleerde opbrengst te berekenen

Hoe een geïsoleerde opbrengst te berekenen

NASA volgt tropische storm Sarai die weggaat van Fiji

NASA volgt tropische storm Sarai die weggaat van Fiji Atmosferische wetenschappers beginnen veldcampagne om extreme onweersbuien in Argentinië te bestuderen

Atmosferische wetenschappers beginnen veldcampagne om extreme onweersbuien in Argentinië te bestuderen Luchtvervuiling veroorzaakt 160, 000 doden in grote steden vorig jaar:NGO

Luchtvervuiling veroorzaakt 160, 000 doden in grote steden vorig jaar:NGO Een positieve kant aan die verschrikkelijke rapporten over klimaatverandering?

Een positieve kant aan die verschrikkelijke rapporten over klimaatverandering? Soorten Pijlstaartrogvissen

Soorten Pijlstaartrogvissen

Hoofdlijnen

- Onderzoekers schijnen de schijnwerpers op illegale handel in wilde orchideeën

- Atrazine verandert de sex-ratio in Blanchards krekelkikkers

- Hoe herstelt de huid?

- Soorten redeneren in geometrie

- Onkruidverdelger glyfosaat, controversieel maar nog steeds het meest gebruikt

- Wat zijn purines en pyrimidines?

- Overeenkomsten tussen verbranding en cellulaire ademhaling

- Carnivoren weten dat het eten van andere karkassen van carnivoren ziekten overdraagt

- Zijn mensen echt afstammelingen van apen?

- Satellietstelsels van de Melkweg helpen bij het testen van de theorie van donkere materie

- Spectraal-volumetrisch gecomprimeerde ultrasnelle fotografie legt tegelijkertijd 5D-gegevens vast in een enkele snapshot

- Kwantumsnelkoppelingen kunnen de wetten van de thermodynamica niet omzeilen

- Wat is het verschil tussen weerstand en geleidbaarheid?

- Wat is de perfecte kwantumtheorie?

Nieuwe geologische vondsten uit het oosten van Fennoscandia voegen nieuwe dimensies toe aan de geschiedenis van de Europese ijstijd

Nieuwe geologische vondsten uit het oosten van Fennoscandia voegen nieuwe dimensies toe aan de geschiedenis van de Europese ijstijd Ben je veilig voor bliksem als je 30 minuten lang geen donder hebt gehoord?

Ben je veilig voor bliksem als je 30 minuten lang geen donder hebt gehoord?  Zeedieren kunnen ons horen zwemmen, kajak en duiken

Zeedieren kunnen ons horen zwemmen, kajak en duiken Death Valley vestigt voorlopig wereldrecord voor warmste maand (update)

Death Valley vestigt voorlopig wereldrecord voor warmste maand (update) Delen van de gloeilamp

Delen van de gloeilamp Waar moet je op letten tijdens de totale zonsverduistering? Een paar niet-van-de-wereld-highlights

Waar moet je op letten tijdens de totale zonsverduistering? Een paar niet-van-de-wereld-highlights Hoe een model van een lawine te maken

Hoe een model van een lawine te maken Het zit allemaal in de oren:de binnenoren van uitgestorven zeemonsters weerspiegelen die van de dieren van vandaag

Het zit allemaal in de oren:de binnenoren van uitgestorven zeemonsters weerspiegelen die van de dieren van vandaag

- Elektronica

- Biologie

- Zonsverduistering

- Wiskunde

- French | Italian | Spanish | Portuguese | German | Dutch | Danish | Norway | Swedish |

-

Wetenschap © https://nl.scienceaq.com