Wetenschap

Door kunstmatige intelligentie versterkte journalistiek biedt een glimp van de toekomst van de kenniseconomie

Robots houden de pennen nog niet vast, maar ze kunnen mensen helpen het werk te doen. Krediet:Paul Fleet/Shutterstock.com

Net zoals robots hele delen van de productie-economie hebben getransformeerd, kunstmatige intelligentie en automatisering veranderen nu het informatiewerk, mensen cognitieve arbeid laten overdragen aan computers. In de journalistiek, bijvoorbeeld, dataminingsystemen waarschuwen journalisten voor mogelijke nieuwsberichten, terwijl nieuwsbots nieuwe manieren bieden voor het publiek om informatie te verkennen. Geautomatiseerde schrijfsystemen genereren financiële, verslaggeving over sport en verkiezingen.

Een veel voorkomende vraag, aangezien deze intelligente technologieën in verschillende industrieën infiltreren, is hoe werk en arbeid zullen worden beïnvloed. In dit geval, wie – of wat – journalistiek gaat doen in deze door AI verbeterde en geautomatiseerde wereld, en hoe gaan ze dat doen?

Het bewijs dat ik heb verzameld in mijn nieuwe boek "Automating the New:How Algorithms are Rewriting the Media" suggereert dat er in de toekomst van AI-enabled journalistiek nog genoeg mensen in de buurt zullen zijn. Echter, de banen, rollen en taken van die mensen zullen evolueren en er een beetje anders uitzien. Menselijk werk zal worden gehybridiseerd - vermengd met algoritmen - om te passen bij de mogelijkheden van AI en om tegemoet te komen aan de beperkingen ervan.

vergroten, niet vervangend

Sommige schattingen suggereren dat de huidige niveaus van AI-technologie slechts ongeveer 15% van het werk van een verslaggever en 9% van het werk van een redacteur kunnen automatiseren. Mensen hebben nog steeds een voorsprong op niet-Hollywood AI op verschillende belangrijke gebieden die essentieel zijn voor journalistiek, inclusief complexe communicatie, deskundig denken, aanpassingsvermogen en creativiteit.

Rapportage, luisteren, reageren en terugduwen, onderhandelen met bronnen, en dan de creativiteit hebben om het samen te stellen - AI kan geen van deze onmisbare journalistieke taken uitvoeren. Het kan vaak menselijk werk versterken, Hoewel, om mensen te helpen sneller of met betere kwaliteit te werken. En het kan nieuwe kansen creëren om de berichtgeving te verdiepen en persoonlijker te maken voor een individuele lezer of kijker.

Newsroom-werk heeft zich altijd aangepast aan golven van nieuwe technologie, inclusief fotografie, telefoons, computers, of zelfs alleen het kopieerapparaat. Journalisten zullen zich aanpassen aan het werken met AI, te. Als technologie, het is en zal het nieuwswerk al veranderen, vaak een aanvulling op maar zelden een vervanging voor een opgeleide journalist.

Nieuw werk

Ik heb dat vaker wel dan niet ontdekt, AI-technologieën lijken daadwerkelijk nieuwe soorten werk in de journalistiek te creëren.

Neem bijvoorbeeld de Associated Press, die in 2017 het gebruik van computer vision AI-technieken introduceerde om de duizenden nieuwsfoto's die het elke dag verwerkt te labelen. Het systeem kan foto's taggen met informatie over wat of wie op een afbeelding staat, zijn fotografische stijl, en of een afbeelding grafisch geweld weergeeft.

Het systeem geeft foto-editors meer tijd om na te denken over wat ze moeten publiceren en voorkomt dat ze veel tijd besteden aan het labelen van wat ze hebben. Maar het ontwikkelen ervan vergde een hoop werk, zowel redactioneel als technisch:redacteuren moesten uitzoeken wat ze moesten taggen en of de algoritmen aan de taak voldeden, ontwikkel vervolgens nieuwe testdatasets om de prestaties te evalueren. Toen dat allemaal gedaan was, ze moesten nog steeds toezicht houden op het systeem, handmatig de voorgestelde tags voor elke afbeelding goedkeuren om een hoge nauwkeurigheid te garanderen.

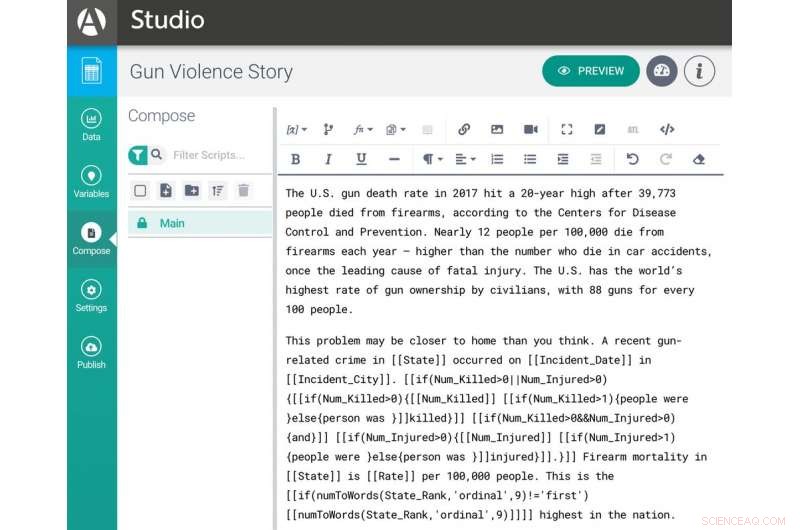

De gebruikersinterface van Arria Studio met de samenstelling van een persoonlijk verhaal over wapengeweld. Credit:Nicholas Diakopoulos screenshot van Arria Studio, CC BY-ND

Stuart Myles, de AP-manager die toezicht houdt op het project, vertelde me dat het ongeveer 36 persoonsmaanden werk kostte, spread over a couple of years and more than a dozen editorial, technical and administrative staff. About a third of the work, he told me, involved journalistic expertise and judgment that is especially hard to automate. While some of the human supervision may be reduced in the future, he thinks that people will still need to do ongoing editorial work as the system evolves and expands.

Semi-automated content production

In the United Kingdom, the RADAR project semi-automatically pumps out around 8, 000 localized news articles per month. The system relies on a stable of six journalists who find government data sets tabulated by geographic area, identify interesting and newsworthy angles, and then develop those ideas into data-driven templates. The templates encode how to automatically tailor bits of the text to the geographic locations identified in the data. Bijvoorbeeld, a story could talk about aging populations across Britain, and show readers in Luton how their community is changing, with different localized statistics for Bristol. The stories then go out by wire service to local media who choose which to publish.

The approach marries journalists and automation into an effective and productive process. The journalists use their expertise and communication skills to lay out options for storylines the data might follow. They also talk to sources to gather national context, and write the template. The automation then acts as a production assistant, adapting the text for different locations.

RADAR journalists use a tool called Arria Studio, which offers a glimpse of what writing automated content looks like in practice. It's really just a more complex interface for word processing. The author writes fragments of text controlled by data-driven if-then-else rules. Bijvoorbeeld, in an earthquake report you might want a different adjective to talk about a quake that is magnitude 8 than one that is magnitude 3. So you'd have a rule like, IF magnitude> 7 THEN text ="strong earthquake, " ELSE IF magnitude <4 THEN text ="minor earthquake." Tools like Arria also contain linguistic functionality to automatically conjugate verbs or decline nouns, making it easier to work with bits of text that need to change based on data.

Authoring interfaces like Arria allow people to do what they're good at:logically structuring compelling storylines and crafting creative, nonrepetitive text. But they also require some new ways of thinking about writing. Bijvoorbeeld, template writers need to approach a story with an understanding of what the available data could say—to imagine how the data could give rise to different angles and stories, and delineate the logic to drive those variations.

Supervision, management or what journalists might call "editing" of automated content systems are also increasingly occupying people in the newsroom. Maintaining quality and accuracy is of the utmost concern in journalism.

RADAR has developed a three-stage quality assurance process. First, a journalist will read a sample of all of the articles produced. Then another journalist traces claims in the story back to their original data source. As a third check, an editor will go through the logic of the template to try to spot any errors or omissions. It's almost like the work a team of software engineers might do in debugging a script—and it's all work humans must do, to ensure the automation is doing its job accurately.

Developing human resources

Initiatives like those at the Associated Press and at RADAR demonstrate that AI and automation are far from destroying jobs in journalism. They're creating new work—as well as changing existing jobs. The journalists of tomorrow will need to be trained to design, update, tweak, validate, correct, supervise and generally maintain these systems. Many may need skills for working with data and formal logical thinking to act on that data. Fluency with the basics of computer programming wouldn't hurt either.

As these new jobs evolve, it will be important to ensure they're good jobs—that people don't just become cogs in a much larger machine process. Managers and designers of this new hybrid labor will need to consider the human concerns of autonomy, effectiveness and usability. But I'm optimistic that focusing on the human experience in these systems will allow journalists to flourish, and society to reap the rewards of speed, breadth of coverage and increased quality that AI and automation can offer.

Dit artikel is opnieuw gepubliceerd vanuit The Conversation onder een Creative Commons-licentie. Lees het originele artikel.

De toekomst cementeren

De toekomst cementeren Nieuwe kristallijne ijsvorm:wetenschappers verhelderen kristalstructuur voor exotisch ijs XIX

Nieuwe kristallijne ijsvorm:wetenschappers verhelderen kristalstructuur voor exotisch ijs XIX Hoe de hoeveelheid afgegeven warmte te berekenen

Hoe de hoeveelheid afgegeven warmte te berekenen  Koffiedik is veelbelovend als houtvervanger bij de productie van nanovezels van cellulose

Koffiedik is veelbelovend als houtvervanger bij de productie van nanovezels van cellulose Botverband neemt pro-genezende biochemische stoffen op om reparatie te versnellen

Botverband neemt pro-genezende biochemische stoffen op om reparatie te versnellen

Hoofdlijnen

- Wat moet er gebeuren met de DNA-strengen in de kern voordat de cel kan delen?

- Bronnen van het lactase-enzym

- De koning van de gewassen kronen:het genoom van de witte Guinea-yam bepalen

- Waarom blijven liedjes in mijn hoofd hangen?

- Microbioomtransplantaties bieden ziekteresistentie in ernstig bedreigde Hawaiiaanse plant

- Stamcelvaccins: de nieuwe grens in kanker-therapie?

- Colombia - een megadivers paradijs dat nog ontdekt moet worden

- Ondergewaardeerde microben krijgen nu de eer voor het behouden van twee banen in de bodem

- Wat is Meiotic Interphase?

- Het systeem helpt planners bij het identificeren, prioriteit geven aan snelwegprojecten

- EmoSense:een door AI aangedreven en draadloos emotiedetectiesysteem

- Review:Facebooks Portal TV is videochat op zijn best. Jammer dat het van Facebook komt

- Wat u moet weten voordat u op Ik ga akkoord met de servicevoorwaardenovereenkomst

- VS prijst Duitse 5G-standaarden terwijl Huawei-strijd suddert

Hoe een ampèremeter aan te sluiten

Hoe een ampèremeter aan te sluiten  Nieuwe fotoakoestische techniek detecteert gassen op het niveau van deeltjes per quadriljoen

Nieuwe fotoakoestische techniek detecteert gassen op het niveau van deeltjes per quadriljoen Welke dieren eten klaver?

Welke dieren eten klaver?  Inzicht in interface-eigenschappen van grafeen maakt de weg vrij voor nieuwe toepassingen

Inzicht in interface-eigenschappen van grafeen maakt de weg vrij voor nieuwe toepassingen Nitraatvervuiling van Amerikaans leidingwater kan 12, 500 kankergevallen per jaar

Nitraatvervuiling van Amerikaans leidingwater kan 12, 500 kankergevallen per jaar Snelle identificatie van hoogwaardige, katalysatoren met meerdere elementen

Snelle identificatie van hoogwaardige, katalysatoren met meerdere elementen Antarctische zeehonden onthullen zorgwekkende bedreigingen voor verdwijnende gletsjers

Antarctische zeehonden onthullen zorgwekkende bedreigingen voor verdwijnende gletsjers Hoe zorgen pijlstaartroggen voor hun jongen

Hoe zorgen pijlstaartroggen voor hun jongen

- Elektronica

- Biologie

- Zonsverduistering

- Wiskunde

- French | Italian | Spanish | Portuguese | Swedish | German | Dutch | Danish | Norway |

-

Wetenschap © https://nl.scienceaq.com