Wetenschap

Kunststoffen, brandstoffen en chemische grondstoffen uit CO2? Ze werken eraan

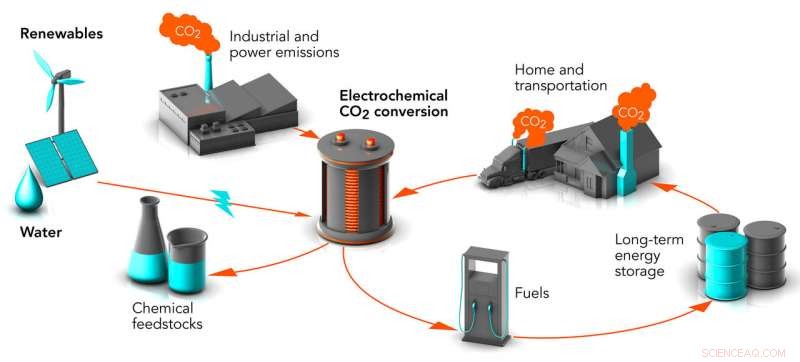

Onderzoekers van Stanford en SLAC werken aan manieren om afvalkooldioxide (CO2) om te zetten in chemische grondstoffen en brandstoffen, het omzetten van een krachtig broeikasgas in waardevolle producten. Het proces wordt elektrochemische conversie genoemd. Wanneer aangedreven door hernieuwbare energiebronnen, het zou de hoeveelheid koolstofdioxide in de lucht kunnen verlagen en energie van deze intermitterende bronnen kunnen opslaan in een vorm die op elk moment kan worden gebruikt. Krediet:Greg Stewart/SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

Een manier om het kooldioxidegehalte in de atmosfeer te verlagen, die nu op zijn hoogste punt in 800 staat, 000 jaar, zou zijn om het krachtige broeikasgas uit de schoorstenen van fabrieken en energiecentrales te vangen en hernieuwbare energie te gebruiken om het om te zetten in dingen die we nodig hebben, zegt Thomas Jaramillo.

Als directeur van SUNCAT Center for Interface Science and Catalysis, een gezamenlijk instituut van Stanford University en het SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory van het Department of Energy, hij is in een positie om dat te helpen realiseren.

Een belangrijk aandachtspunt van SUNCAT-onderzoek is het vinden van manieren om CO . te transformeren 2 in chemicaliën, brandstoffen, en andere producten, van methanol tot plastic, wasmiddelen en synthetisch aardgas. De productie van deze chemicaliën en materialen uit ingrediënten van fossiele brandstoffen is nu goed voor 10% van de wereldwijde koolstofemissies; de productie van benzine, diesel, en vliegtuigbrandstof is goed voor veel, veel meer.

"We hebben al te veel CO . uitgestoten 2 , en we zijn op schema om het jarenlang te blijven uitstoten, aangezien 80% van de energie die momenteel wereldwijd wordt verbruikt, afkomstig is van fossiele brandstoffen, " zegt Stephanie Nitopi, wiens SUNCAT-onderzoek de basis vormt van haar nieuw verworven Stanford Ph.D.

"Je zou CO . kunnen afvangen 2 uit schoorstenen en bewaar het ondergronds, " zegt ze. "Dat is een technologie die momenteel in het spel is. Een alternatief is om het te gebruiken als grondstof voor het maken van brandstoffen, kunststoffen, en speciale chemicaliën, die het financiële paradigma verschuift. Afval CO 2 emissies worden nu iets dat je kunt recyclen tot waardevolle producten, een nieuwe stimulans geven om de hoeveelheid CO . te verminderen 2 vrijgelaten in de atmosfeer. Dat is een win-winsituatie."

We vroegen Nitopi, Jaramillo, SUNCAT-stafwetenschapper Christopher Hahn en postdoctoraal onderzoeker Lei Wang om ons te vertellen waar ze aan werken en waarom het ertoe doet.

Q. Eerst de basis:hoe zet je CO . om 2 in deze andere producten?

Tom:Het is in wezen een vorm van kunstmatige fotosynthese, daarom financiert DOE's Joint Centre for Artificial Photosynthesis ons werk. Planten gebruiken zonne-energie om CO . om te zetten 2 uit de lucht in koolstof in hun weefsels. evenzo, we willen technologieën ontwikkelen die gebruik maken van hernieuwbare energie, zoals zon of wind, om CO . om te zetten 2 van industriële emissies tot op koolstof gebaseerde producten.

Chris:Een manier om dit te doen heet elektrochemische CO 2 vermindering, waar je CO . bubbelt 2 gas omhoog door water en het reageert met het water op het oppervlak van een op koper gebaseerde elektrode. Het koper werkt als een katalysator, het samenbrengen van de chemische ingrediënten op een manier die hen aanmoedigt om te reageren. Heel simpel gezegd, de eerste reactie ontdoet een zuurstofatoom van CO 2 om koolmonoxide te vormen, of CO, wat op zichzelf al een belangrijke industriële chemische stof is. Dan zetten andere elektrochemische reacties CO om in belangrijke moleculen zoals alcoholen, brandstoffen en andere zaken.

Tegenwoordig vereist dit proces een op koper gebaseerde katalysator. Het is de enige die het werk doet. Maar deze reacties kunnen tal van producten produceren, en het scheiden van degene die je wilt is kostbaar, dus we moeten nieuwe katalysatoren identificeren die de reactie kunnen sturen om alleen het gewenste product te maken.

Hoezo?

Lei:Als het gaat om het verbeteren van de prestaties van een katalysator, een van de belangrijkste dingen waar we naar kijken, is hoe we ze selectiever kunnen maken, dus ze genereren slechts één product en niets anders. Ongeveer 90 procent van de brandstof- en chemische productie is afhankelijk van katalysatoren, en het wegwerken van ongewenste bijproducten is een groot deel van de kosten.

We kijken ook hoe we katalysatoren efficiënter kunnen maken door hun oppervlakte te vergroten, er zijn dus veel meer plaatsen in een bepaald volume materiaal waar gelijktijdig reacties kunnen plaatsvinden. Dit verhoogt de productiesnelheid.

Onlangs ontdekten we iets verrassends:toen we het oppervlak van een op koper gebaseerde katalysator vergrootten door het te vormen tot een vlokkige "nanobloem"-vorm, het maakte de reactie zowel efficiënter als selectiever. In feite, it produced virtually no byproduct hydrogen gas that we could measure. So this could offer a way to tune reactions to make them more selective and cost-competitive.

Stephanie:This was so surprising that we decided to revisit all the research we could find on catalyzing electrochemical CO 2 conversion with copper, and the many ways people have tried to understand and fine-tune the process, using both theory and experiments, going back four decades. There's been an explosion of research on this—about 60 papers had been published as of 2006, versus more than 430 out there today—and analyzing all the studies with our collaborators at the Technical University of Denmark took two years.

We were trying to figure out what makes copper special, why it's the only catalyst that can make some of these interesting products, and how we can make it even more efficient and selective—what techniques have actually pushed the needle forward? We also offered our perspectives on promising research directions.

One of our conclusions confirms the results of the earlier study:The copper catalyst's surface area can be used to improve both the selectivity and overall efficiency of reactions. So this is well worth considering as a chemical production strategy.

Does this approach have other benefits?

Tom:Absolutely. If we use clean, renewable energy, like wind or solar, to power the controlled conversion of waste CO 2 to a wide range of other products, this could actually draw down levels of CO 2 in the atmosphere, which we will need to do to stave off the worst effects of global climate change.

Chris:And when we use renewable energy to convert CO 2 to fuels, we're storing the variable energy from those renewables in a form that can be used any time. In aanvulling, with the right catalyst, these reactions could take place at close to room temperature, instead of the high temperatures and pressures often needed today, making them much more energy efficient.

How close are we to making it happen?

Tom:Chris and I explored this question in a recent Perspective article in Wetenschap , written with researchers from the University of Toronto and TOTAL American Services, which is an oil and gas exploration and production services firm.

We concluded that renewable energy prices would have to fall below 4 cents per kilowatt hour, and systems would need to convert incoming electricity to chemical products with at least 60% efficiency, to make the approach economically competitive with today's methods.

Chris:This switch couldn't happen all at once; the chemical industry is too big and complex for that. So one approach would be to start with making high-value, high-volume products like ethylene, which is used to make alcohols, polyester, antifreeze, plastics and synthetic rubber. It's a $230 billion global market today. Switching from fossil fuels to CO 2 as a starting ingredient for ethylene in a process powered by renewables could potentially save the equivalent of about 860 million metric tons of CO 2 emissions per year.

The same step-by-step approach applies to sources of CO 2 . Industry could initially use relatively pure CO 2 emissions from cement plants, breweries or distilleries, bijvoorbeeld, and this would have the side benefit of decentralizing manufacturing. Every country could provide for itself, develop the technology it needs, and give its people a better quality of life.

Tom:Once you enter certain markets and start scaling up the technology, you can attack other products that are tougher to make competitively today. What this paper concludes is that these new processes have a chance to change the world.

Valse verhalen beweren dat NASA bekende lithium te hebben verspreid

Valse verhalen beweren dat NASA bekende lithium te hebben verspreid Grote hoeveelheden waardevolle energie, voedingsstoffen, water verloren in snel stijgende afvalwaterstromen ter wereld

Grote hoeveelheden waardevolle energie, voedingsstoffen, water verloren in snel stijgende afvalwaterstromen ter wereld Manieren om het broeikaseffect te verminderen

Manieren om het broeikaseffect te verminderen Shell getroffen door Nederlandse klimaatrechtszaak

Shell getroffen door Nederlandse klimaatrechtszaak Bij klimaatomkering, Biden stemt in met nieuwe megaveiling voor olie en gas

Bij klimaatomkering, Biden stemt in met nieuwe megaveiling voor olie en gas

Hoofdlijnen

- Difference Between Triglycerides & Phospholipids

- Vergroening van citrusvruchten behandelen met koper:effecten op bomen, bodems

- Geometrie speelt een belangrijke rol in hoe cellen zich gedragen, onderzoekers rapporteren

- Wat is de structurele classificatie van het zenuwstelsel?

- Vogels onthullen het belang van goede buren voor gezondheid en veroudering

- Welke sequenties zorgen ervoor dat DNA uitpakt en ademt?

- Welk deel van het lichaam maakt bloed?

- Een mogelijke verklaring voor hoe kiemlijnen worden verjongd

- Het Mandela-effect:waarom we ons gebeurtenissen herinneren die niet hebben plaatsgevonden

- Met een meerlagige aanpak, een filter om te voldoen aan de behoeften van de zoetwatervoorziening

- Atoomafbeeldingen onthullen veel buren voor sommige zuurstofatomen

- Wetenschappers ontwikkelen snelle chemie die een nieuwe klasse polymeren ontsluit

- Pavlovs klassieke conditionering inspireert materiaalwetenschappers

- Leren van fotosynthese:synthetische circuits kunnen lichtenergie oogsten

Machine learning kan een game-changer zijn voor klimaatvoorspelling

Machine learning kan een game-changer zijn voor klimaatvoorspelling Hoe klimaatverandering en branden de bossen van de toekomst vormgeven

Hoe klimaatverandering en branden de bossen van de toekomst vormgeven Bill wil miljarden uitgeven om verouderde dammen in landen te repareren

Bill wil miljarden uitgeven om verouderde dammen in landen te repareren Computers strijden mee tegen COVID-19

Computers strijden mee tegen COVID-19 Ruimtetoerisme:het aanbod

Ruimtetoerisme:het aanbod Hoe maak je een spiraal vanuit de stelling van Pythagoras

Hoe maak je een spiraal vanuit de stelling van Pythagoras Snelheid geïdentificeerd als beste voorspeller van auto-ongelukken

Snelheid geïdentificeerd als beste voorspeller van auto-ongelukken Wat zijn alfa-, bèta- en gammadeeltjes?

Wat zijn alfa-, bèta- en gammadeeltjes?

- Elektronica

- Biologie

- Zonsverduistering

- Wiskunde

- French | Italian | Spanish | Portuguese | Swedish | German | Dutch | Danish | Norway |

-

Wetenschap © https://nl.scienceaq.com