Wetenschap

Hoe zou een realistisch ruimtegevecht eruitzien?

Krediet:Pixabay/CC0 publiek domein

Sciencefiction-ruimtefilms kunnen mensen slecht informeren over de ruimte. In de films, hot-shot piloten sturen hun duellerende ruimteschepen door de ruimte alsof ze door een atmosfeer vliegen. Ze buigen en draaien en voeren lussen en rollen uit, misschien een snelle Immelman beurt geven, alsof ze onderhevig zijn aan de zwaartekracht van de aarde. Is dat realistisch?

Nee.

In werkelijkheid, een ruimtegevecht zal er waarschijnlijk heel anders uitzien. Met een toenemende aanwezigheid in de ruimte, en het potentieel voor toekomstige conflicten, is het tijd om na te denken over hoe een echte ruimtestrijd eruit zou zien?

De non-profit Aerospace Corporation denkt dat het tijd is om na te denken over hoe een echte ruimtestrijd eruit zou zien. Dr. Rebecca Reesman van het Center for Space Policy and Strategy van de Aerospace Corporation en haar collega James R. Wilson hebben een paper geschreven over ruimtegevechten, getiteld "The Physics of Space War:How Orbital Dynamics Constrain Space-to-Space Engagements."

Als menselijke aangelegenheden uit het verleden de toekomst aangeven, dan zal de militarisering van de ruimte doorgaan. Dat is ondanks het praten over het vreedzaam houden van de ruimte, en ondanks verdragen die hetzelfde zeggen. Het is dus belangrijk dat naarmate meer landen hun aanwezigheid in de ruimte vergroten, en als een concurrentie om middelen problemen begint te veroorzaken, dat het gesprek over ruimteconflict een realistische wending neemt.

Dat is het geval dat de auteurs maken in de inleiding van hun paper. "Terwijl de Verenigde Staten en de wereld de mogelijkheid bespreken dat een conflict zich uitbreidt tot in de ruimte, het is belangrijk om een algemeen begrip te hebben van wat fysiek mogelijk en praktisch is. Scènes uit Star Wars, boeken en tv-programma's laten een wereld zien die heel anders is dan wat we de komende 50 jaar waarschijnlijk zullen zien, als ooit, gegeven de wetten van de fysica."

Een Sovjet Almaz bemand ruimtestation in het Cosmonautics and Aviation Center in Moskou. Rusland heeft verschillende soorten militaire satellieten en ruimtestations ontworpen, sommigen gewapend met een machinegeweer, alvorens het idee als te duur te laten varen. Credit:Door Pulux11 – Eigen werk, CC BY-SA 4.0

Er is nog nooit een gevecht in de ruimte geweest. Maar er zijn wat wapentestactiviteiten geweest. China werkt aan anti-satellietwapens en heeft een anti-satellietraket getest. Zo ook Indië. Rusland werkt ook aan antisatellietcapaciteiten, en de VS doen hetzelfde. De VS hebben in 1985 een van hun eigen satellieten met een raket vernietigd.

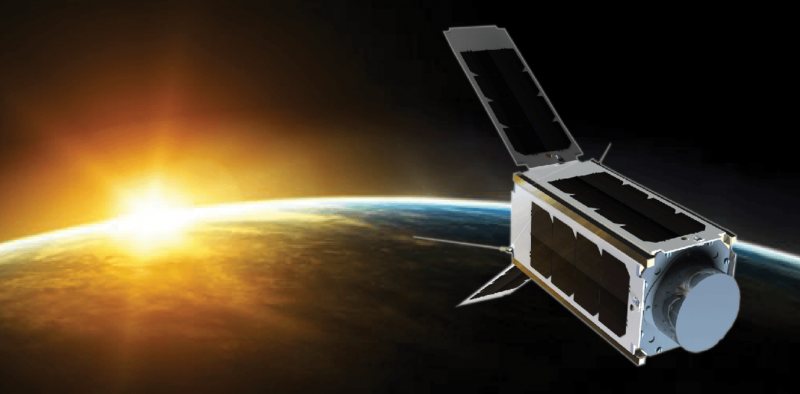

Dit is waarschijnlijk slechts het topje van de ijsberg als het gaat om toekomstige conflicten in de ruimte. Bij geen van deze anti-satellietactiviteiten waren mensen betrokken die in ruimtevaartuigen reisden, en er is misschien nooit behoefte aan bemande militaire ruimtevaartuigen, volgens het papier. "De ruimte-tot-ruimte-opdrachten in een modern conflict zouden alleen worden uitgevochten met onbemande voertuigen die worden bestuurd door operators op de grond en zwaar worden beperkt door de limieten die de fysica oplegt aan beweging in de ruimte."

In de begindagen van het ruimtetijdperk, terwijl de Koude Oorlog nog woedde, de supermachten dachten dat conflicten in de ruimte grotendeels een verlengstuk zouden zijn van aardse conflicten. De Sovjets ontwierpen zelfs ruimtestations bewapend met een machinegeweer om zich te verdedigen tegen aanvallen van Amerikaanse astronauten. De VS werkten aan soortgelijke ideeën.

Maar technologische vooruitgang betekende dat die inspanningen werden opgegeven ten gunste van onbemande satellieten. "Eventueel, beide programma's haperden. In plaats daarvan, verbeteringen in technologie en datatransmissie - dezelfde ontwikkelingen die uiteindelijk ten grondslag liggen aan ons moderne verbonden leven - maakten satellieten mogelijk die dezelfde militaire functies vervullen als voor de eerdere bemande programma's." Nu, ruimte wordt gedomineerd door satellieten, met alleen het ISS als gastheer voor mensen.

Dit wordt de toekomst, volgens het papier. Voor de komende 50 jaar of zo, eventuele conflicten in de ruimte zullen aanvallen op satellieten met zich meebrengen. Maar niet alles zal een regelrechte aanval zijn. De auteurs schetsen vier doelen bij een ruimteaanval:

Ruimtegevechten zullen waarschijnlijk plaatsvinden tussen satellieten, en tanken is geen optie. Op deze afbeelding, een F-16 tankt uit een KC-135 Stratotanker. Krediet:door de Amerikaanse luchtmacht

- Bedrieg een vijand zodat ze reageren op een manier die hun belangen schaadt.

- verstoren, ontkennen, of het vermogen van een vijand om een ruimtevermogen te gebruiken verminderen, tijdelijk of permanent.

- Vernietig een ruimtegebaseerd vermogen volledig.

- Afschrikken of verdedigen tegen een tegenaanval tegenstander, hetzij in de ruimte of op aarde.

Satellieten bewegen zeer voorspelbaar. Ze bewegen snel, maar het is relatief eenvoudig om hun toekomstige positie te voorspellen en te onderscheppen, vaak. Sommige satellieten kunnen hun baanhoogte veranderen, maar ze hebben geen echte wendbaarheid en bijna geen manier om een aanval te vermijden.

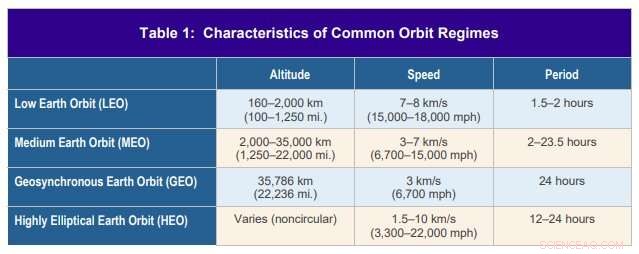

"Om te beschrijven hoe de natuurkunde ruimte-tot-ruimte-opdrachten zou beperken, dit artikel beschrijft vijf sleutelconcepten:satellieten bewegen snel, satellieten bewegen voorspelbaar, ruimte is groot, tijd is alles, en satellieten manoeuvreren langzaam."

Vluchten door de atmosfeer van de aarde is niet bepaald eenvoudig, maar het is vrij intuïtief. Maar in de ruimte, het is compleet anders en wordt niet nauwkeurig vlucht genoemd. Zonder atmosfeer en lage zwaartekracht, dingen zijn heel anders. "Beweging in de ruimte is contra-intuïtief voor degenen die gewend zijn aan vliegen in de atmosfeer van de aarde en de kans om te tanken, ’ schrijven de auteurs.

"Ruimte-naar-ruimte-opdrachten zouden opzettelijk zijn en zich waarschijnlijk langzaam ontvouwen omdat de ruimte groot is en ruimtevaartuigen alleen met grote inspanning aan hun voorspelbare paden kunnen ontsnappen. Bovendien, aanvallen op ruimtemiddelen zouden precisie vereisen, omdat ruimtevaartuigen en zelfs wapens op de grond alleen doelen in de ruimte kunnen aanvallen nadat complexe berekeningen zijn bepaald in een hoog ontwikkeld domein." Er zou geen kader van jachtpiloten stand-by staan, wachtend om te klauteren en snel te lanceren. In plaats daarvan, een ruimtegevecht met satellieten is meer een wiskundige oefening.

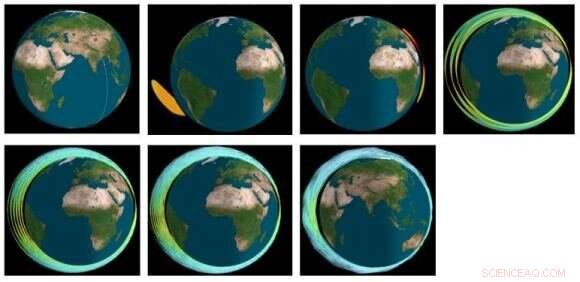

De banen van satellieten zijn voorspelbaar en zijn niet afhankelijk van de massa van de satelliet. Krediet:Reesman en Wilson 2020.

"This is true because physics puts constraints on what happens in space. Only by mastering these constraints can other questions such as how to fight and, het belangrijkste, when and why to fight a war in space, be explored, " zij schrijven.

A satellite's orbit is predictable because of the relationship between speed, altitude and the orbit's shape. At lower altitudes, satellites can experience atmospheric drag. Ook, the Earth isn't a perfect sphere. But those factors can be accounted for in an attack. "To deviate from their prescribed orbit, satellites must use an engine to maneuver. This contrasts with airplanes, which mostly use air to change direction; the vacuum of space offers no such option, " zij schrijven.

The sheer volume of space is also a factor in a space battle. "The volume of space between LEO and GEO is about 200 trillion cubic kilometers (50 trillion cubic miles). That is 190 times bigger than the volume of Earth."

So tracking satellites accurately in that volume of space will be a continuous challenge, since some will be designed to be undetected. But that's not impossible; satellites are regularly tracked. And since they're not very maneuverable, once a satellite's orbit is detected, monitors can keep track of its trajectory.

The sheer volume of space also means that most space battles would be very short-lived. There won't be any dogfights. "Space is big, which means that a space-to-space engagement is not going to be both intense and long. It can only be one or the other:either a short, intense use of a lot of Delta V for big effect or long, deliberate use of Delta V for smaller or persistent effects."

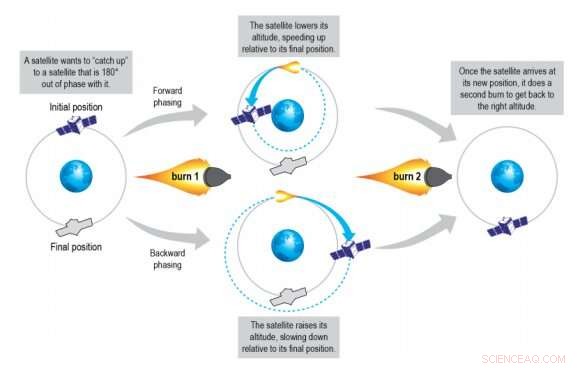

Satellites change their position in their orbit with phasing maneuvers. Any time a satellite raises its orbit, it slows down and appears to be moving backward in relation to its prior orbit and altitude. This is how a satellite can “catch up” to another satellite. Credit:Reesman and Wilson 2020

Delta V is a change in velocity, and that requires fuel or propellant. But most satellites don't have the capability to change their velocity, and the few that might are severely fuel-limited.

"Operators of an attack satellite may spend weeks moving a satellite into an attack position during which conditions may have changed that alter the need for or the objective of the attack." And if the defending satellite is able to only slightly change its own path in response to an attack, then the attacking satellite may not have the capability or the fuel to change its own path to intercept it.

The authors also point out that timing is everything. Even if an attacking satellite can orient itself into the same orbital path as its target, there's still no guarantee of proximity.

"The nature of conflict often requires two competing weapons systems to get close to one another, " the report says. The authors use the example of an aircraft carrier needing to get close to its target, and another of jet fighters that also need to be close to each other. The same thing is true of satellites in space.

"Getting two satellites to the same altitude and the same plane is straightforward (though time and ?V consuming), but that does not mean they are yet in the same spot. The phasing—current location along the orbital trajectory—of the two satellites must also be the same. Since speed and altitude are connected, getting two satellites in the same spot is not intuitive." Instead, it takes perfect timing and meticulous preparation.

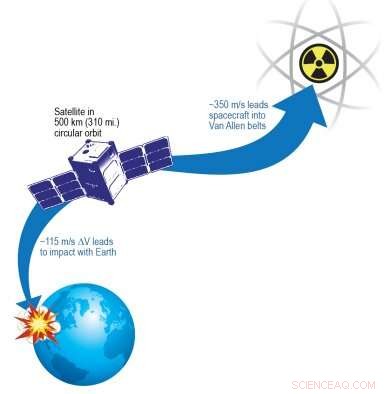

If a satellite performs a forward phasing maneuver with a first burn of 115 m/s or more of ?V, it will reenter Earth’s atmosphere and burn up. evenzo, if the satellite performs a backward phasing maneuver with a first burn of 350 m/s or more of ?V, it will experience high radiation in the Van Allen belts. These two facts create natural bounds for how quickly a satellite can maneuver in LEO (500 km or 310 mi.). Credit:Reesman and Wilson 2020

The authors also discuss another method of approaching a target called "plane matching, " A satellite maneuvers itself so that its orbital plane is aligned with a target. That has the advantage of allowing the attacker to dictate the time of the engagement. "By not initiating threatening maneuvers immediately, an attacker may try to seem harmless while waiting for an optimal time to attack, " the authors explain.

But none of these maneuvers happen quickly. "The physics of space dictate that kinetic space-to-space engagements be deliberate with satellites maneuvering for days, if not weeks or months, beforehand to get into position to have meaningful operational effects, " they write. But it can still be done.

And once the interception has been set up, "…many opportunities can arise to maneuver close enough to engage a target quickly."

There are natural limits to how maneuvering satellites in LEO can do. Aan de ene kant, some phasing maneuvers can send the satellite into the Earth's atmosphere where it will be burned up. Op de andere, it could be sent too far away from LEO, into the Van Allen Belts. So there are constraints on a satellite's maneuverability.

Satellites in geostationary orbits maintain the same relative position over Earth, so some of the mechanics of attacking and defending are different. Maar over het algemeen, the same constraints are still in place. It takes time and energy to maneuver in space, regardless of the type of orbit.

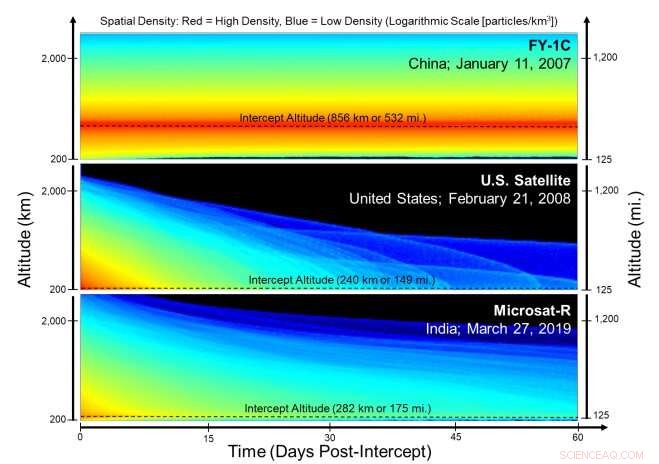

The density of debris is compared at different altitudes as a function of time after the ASAT intercepted (made contact with and destroyed) the target satellite. The Chinese test happened at a much higher altitude (856 km or 532 mi.) than the other two, creating long-lasting debris. Credit:Reesman and Wilson, 2020

But orbital and maneuverability considerations are only a part of what the report addresses.

The authors go on to discuss the types of attacks that can take place. Collisions, projectiles, and electronic jamming or disruption are covered in the paper. Each type has its own considerations and preparations.

But the authors also discuss the aftermath of some successful attacks:complications arising from debris. Additional debris could end up damaging other unintentional targets, like the attacker's own satellites or those of a neutral nation. There have been three successful anti-satellite attacks:one by China, one by the U.S., en Indië. The authors prepared a graphic to show the debris from each one.

The debris cloud from an attack is denser immediately after the attack and spreads out quickly. Even though debris density is lowered quickly, the debris spreads out over a larger area and is still hazardous.

The paper is a clear presentation of all of the difficulties with space battles and how much different they would be compared to air-to-air battles. But some other considerations that are still important are outside its scope.

This image shows the debris cloud from the Indian ASAT in 2019. The panels show the cloud at 5 min., 45 min., 90 min., 1 day, 2 days, 3 days, and 6 days after the attack. Credit:Reesman and Wilson 2020

What happens when one nation deduces that their satellites are about to be attacked? They won't sit on their thumbs. They'll likely denounce, threaten, and even retaliate here on Earth. A space attack could end up being a flashpoint for another terrestrial war.

There could end up being an arms race in space, where nations compete to outspend each other on space weaponry and other technology. That's a huge strain on resources for a world that should be focused on meeting the challenge of climate change.

En, where does it all end? War in orbit? War on the moon? War on Mars? When will humanity figure it out and just stop?

One day, kan zijn, there'll be a final war before we give it all up. But that won't likely be in the next 50 years.

And if there is a war in the next 50 years or so, it may involve satellites, and it may look a lot like how the authors of this report have laid it out:slow, calculated, and deliberate.

Inname van microplastics door blaas veroorzaakt toxiciteit in utricularia aurea lour

Inname van microplastics door blaas veroorzaakt toxiciteit in utricularia aurea lour Californië stuurde 12 miljoen mensen een sms-bericht over brandgevaar

Californië stuurde 12 miljoen mensen een sms-bericht over brandgevaar De puls van de polaire vortex vinden

De puls van de polaire vortex vinden Hebben elanden ivoren tanden?

Hebben elanden ivoren tanden?  Rechtbank steunt Californische vergoedingen voor vervuilers die limieten overschrijden

Rechtbank steunt Californische vergoedingen voor vervuilers die limieten overschrijden

Hoofdlijnen

- Arbusculaire mycorrhiza-schimmelgemeenschappen blootgesteld met nieuwe benadering van DNA-sequencing

- Wat irriteert een chimpansee?

- Nieuwe soorten ontdekt in Maleisisch regenwoud tijdens ongekende, onderzoek van boven naar beneden

- Fagen een effectief alternatief voor het gebruik van antibiotica in de aquacultuur

- Hoe kan een mutatie in DNA invloed hebben op eiwitsynthese?

- Dansgerelateerde wetenschapsprojecten

- Pompoengenomen gesequenced, ongewone evolutionaire geschiedenis onthullen

- Top 5 onopgeloste hersenmysteries

- Stappen voor het traceren van een plant:zaadverspreiding volgen met behulp van chloroplast-DNA

- Australië is terug in de satellietbusiness met een nieuwe lancering

- Asteroïde komt vrijdag dichtbij:maak je geen zorgen, waren veilig

- Afbeelding:Het ruimtestation bouwen

- Onderzoekers geven nieuwe aanwijzing voor het probleem van de coronale verwarming van de zon

- Water gedetecteerd in de atmosfeer van hete Jupiter-exoplaneet 51 Pegasi b

Onderzoekers ontwikkelen 's werelds dunste elektrische generator

Onderzoekers ontwikkelen 's werelds dunste elektrische generator Ja, klanten vinden het leuk als obers en kappers een masker dragen - vooral als het zwart is

Ja, klanten vinden het leuk als obers en kappers een masker dragen - vooral als het zwart is Verschillen in gegevens kunnen het begrip van het universum beïnvloeden

Verschillen in gegevens kunnen het begrip van het universum beïnvloeden Nieuw bewijs voor natuurlijke synthese van zilveren nanodeeltjes

Nieuw bewijs voor natuurlijke synthese van zilveren nanodeeltjes Ontdekking van een nieuwe massa-extinctie

Ontdekking van een nieuwe massa-extinctie Beter jij dan ik, Trump vertelt recordbrekende astronaut

Beter jij dan ik, Trump vertelt recordbrekende astronaut Elektriciteitsgebruik in de cloud

Elektriciteitsgebruik in de cloud Ancient Egyptian Astrology Facts

Ancient Egyptian Astrology Facts

- Elektronica

- Biologie

- Zonsverduistering

- Wiskunde

- French | Italian | Spanish | Swedish | German | Dutch | Danish | Norway | Portuguese |

-

Wetenschap © https://nl.scienceaq.com