Wetenschap

Hoe menselijke experimenten werken

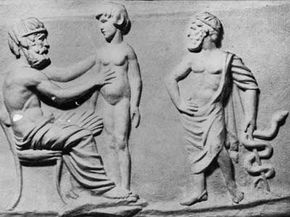

Het is de vierde eeuw voor Christus. en Herophilus, de vader van de anatomie, heft zijn chirurgisch mes op om te glanzen in de Egyptische zon. Overal om hem heen komen artsen uit het hele Middellandse Zeegebied naar hem toe om zijn incisie te aanschouwen, terwijl hij zijn instrument buigt voor de taak die voor hem ligt. Ze hebben al zoveel geleerd over de fysiologie van het oog, hebben de mysteries van de menselijke ingewanden ondergedompeld.

Nogmaals, de meester scheidt vlees, gaat het bloedige doolhof van slagaders en spieren binnen. Bij elke incisie kronkelt het lichaam eronder van de pijn, spant het zich tegen de koorden die hem aan de operatietafel binden - want hij is niet zomaar een kadaver, maar een levende, ademende proefpersoon. Herophilus vervolgt zijn onderzoek, zich niet bewust van het gedempte geschreeuw van de veroordeelde gevangene. De geleerden bespreken de studie van de blootgestelde poroi of zenuwen, zelfs als ze vonken met onvoorstelbare kwelling.

Het was een tijd van grote geleerdheid in de antieke wereld, en Alexandrië was er het centrum van. De familie Ptolemaeus had een museum of "huis van muzen" opgericht voor de vooruitgang van wetenschap en literatuur. De bevindingen van de familie hielpen de legendarische bibliotheek van Alexandrië te vullen en een tijdlang diende de stad als een schans tegen een door onwetendheid overschaduwde wereld. Het verbod op het ontleden van kadavers werd opgeheven.

Gedurende een periode van ongeveer 50 jaar werd zelfs de taboebeoefening van menselijke vivisectie gemeengoed. Immers, geleerden konden maar zoveel leren van een studie van de doden. In een tijd waarin nog werd gedacht dat bloedvaten lucht transporteerden, moesten ze levende lichamen openstellen voor wetenschappelijk onderzoek. Waarom zouden de verlaten levens van de veroordeelden de komende generaties niet ten goede komen?

Herophilus zou naar verluidt bijna 600 levende gevangenen ontleed hebben, waarmee hij zijn plaats in de medische geschiedenis verdiende met zijn verschillende ontdekkingen. Maar zelfs in die tijd uitten veel critici hun onbehagen over vivisectie, ongeacht de beloningen. Zijn geschriften gingen voor altijd verloren in het jaar 272, toen de grote bibliotheek van de stad door brand werd verwoest.

Terwijl we door de eeuwen heen staren, staat Herophilus nauwelijks als een verre flikkering van moreel dilemma. Integendeel, de geschiedenis kronkelt met talloze en verontrustende voorbeelden van menselijke experimenten.

De moderne samenleving staat slechts tientallen jaren verwijderd van enkele van de ergste voorbeelden van onethische experimenten. Zelfs vandaag de dag blijft de medische wetenschap vooruitgang boeken op de rug van menselijke proefpersonen.

Inhoud

- Waarom experimenteren op mensen?

- De donkere kant van de wetenschap:eenheid 731 en nazi-Duitsland

- Wijsheid uit het lijden:leren van menselijke experimenten

- Experimenteren met onwetende onderwerpen

- Moderne klinische geneesmiddelenonderzoeken

- Contant geld voor menselijke cavia's

Waarom experimenteren op mensen?

De kwestie van menselijke experimenten komt over het algemeen neer op een basisfeit:wanneer de wetenschap rechtstreeks met mensen te maken heeft, moet je mensen bestuderen - uiteindelijk. Het is zo simpel. Of je nu kwalen en verwondingen wilt genezen, een veiligere auto wilt bouwen of een dodelijker wapen wilt ontwerpen, het kan zijn dat je menselijke drempels voor ziekte, stress en letsel moet testen.

Een paar andere opties (en ethische obstakels) hebben de neiging zich voor te doen voordat je de leiding van Herophilus neemt en veroordeelde misdadigers begint te snijden. Als je experiment absoluut het gebruik van een menselijke proefpersoon vereist, kun je altijd terugvallen op de dode variant. Ook zonder functie heb je vorm. De beroemde vader van de anatomie gebruikte ze zelf voor veel van zijn onderzoek.

Om nieuwe wegen in te slaan, moesten medische pioniers vaak afhankelijk zijn van de lichamen van geëxecuteerde criminelen of lijken stelen uit graven en galstenen. Lichaamsroof werd een groei-industrie in de 19e eeuw, omdat medische scholen verse lichamen nodig hadden voor jonge chirurgen om op te oefenen. Tegenwoordig kunnen onderzoekers en studenten gemakkelijker toegang krijgen tot juridische medische kadavers.

Soms hebben wetenschappers een levend onderwerp nodig - een werkend model. In veel gevallen wenden ze zich tot de rest van het dierenrijk. Alleen al in de afgelopen eeuw hebben chimpansees, konijnen en andere dieren geholpen bij alles, van polio-onderzoek en ruimteverkenning tot cosmetica en het testen van biowapens.

Afgezien van morele en ethische dilemma's, zijn er twee belangrijke problemen met dierproeven. Ten eerste kan een konijn alleen gedrags- en fysiologische feedback geven. Zelfs de slimste primaat kan geen Q&A invullen. Ten tweede werk je met een niet-menselijke soort, waardoor het moeilijk of onmogelijk wordt om bepaalde mensspecifieke ziekten, kwalen en scenario's te bestuderen.

Zelfexperimenten zijn vaak een zeer succesvol (en roekeloos) middel van wetenschappelijk onderzoek gebleken. Talloze wetenschappers hebben zichzelf met opzet besmet met ziekten of parasieten om uit de eerste hand inzicht te krijgen in het onderwerp. Pierre en Marie Curie ontvingen in 1903 de Nobelprijs voor natuurkunde voor hun stralingsonderzoek, waarbij ze gevaarlijke radiumzouten op hun huid plakten.

Toch heeft zelfexperimenten zijn grenzen. Herophilus kon zijn eigen vivisectie niet hebben uitgevoerd, laat staan 600 afzonderlijke procedures op zichzelf. Een experiment is tenslotte maar één fase in de wetenschappelijke methode -- het heeft geen zin om halverwege dood te gaan. En hoe behoud je functionaliteit en objectiviteit als je lijdt aan de plaag die je hoopt te genezen?

Dan blijven menselijke experimenten over, en alle negatieve connotaties die daarmee gepaard gaan.

The Dark Side of Science:Unit 731 en nazi-Duitsland

Human experimentation doesn't have to be an exercise in cruelty, yet we're not even a century removed from some of the more deplorable acts -- cases that could easily rival and even surpass the alleged crimes of Herophilus and his colleagues.

As in ancient Alexandria, scientists and doctors have often turned to the disenfranchised when the need for test subjects arises. After all, we experiment on animals by telling ourselves that the greater good outweighs the desires of a few lesser creatures. History has shown us where this line of thinking can lead when we see other humans as the lesser creatures in question.

J. Marion Sims is widely considered the father of gynecology and even became the president of the American Medical Association in 1876. Yet Sims developed his experimental surgeries by testing them on African slaves, often without anesthesia.

The United States often turned to prisoners for medical tests, such as the 1906 cholera experiments in the Philippines and the 1915 pellagra experiments in Mississippi. Poor and orphaned children suffered similar fates. In 1908, three Philadelphia physicians infected several orphans with tuberculosis, permanently blinding several. Between 1919 and 1922, Dr. Leo Stanley injected 656 prisoners at San Quentin Prison with animal testis trying to slow or reverse ageing [source:Lunenfeld]. Before the 1970s, roughly 90 percent of all pharmaceutical products were tested on prisoners [source:Proquest].

Yet when it comes to experiments on captives and prisoners, few examples resonate as strongly as the experiments conducted by the Nazis during World War II on Jews, gypsies and other targeted individuals. The doctors conducted cruel and often lethal experiments into wartime injury treatment generally by inflicting said injury on a captive patient. They froze victims to research hypothermia, placed them in compression chambers to test the effects of high-altitude flight. They also conducted brutal sterilization experiments in the name of racial superiority.

Similarly, Japan's infamous Unit 731 reportedly killed more than 10,000 Chinese, Korean and Russian prisoners of war to research and develop biological weapons. They infected inmates and performed vivisections on them, all in an attempt to craft even deadlier weapons out of disease.

How are we supposed to process such atrocities? And what do we do with the data gleaned from degradation and torture?

Wisdom Out of Suffering:Learning from Human Experimentation

Humanity continues to march on through the years, bound to the linear procession of time. Any sober, honest glance back at the path we've traveled is often as horrifying as it is wondrous. Our collective history bristles with atrocity. We can't separate ourselves from it without also draping ourselves again in the cloak of ignorance.

Much the same can be said of science. While it continues to light the way to the future, portions of its momentum were purchased through horrible deeds. But what can we do? No one is arguing that we throw out everything we know about human anatomy in penance for Herophilus' vivisections.

Allied scientists faced such a dilemma at the end of World War II. What were they to do with Unit 731's medical findings on disease? Regardless of the methods used to obtain it, the information was valuable. It was like pondering a gold coin fetched from a vat of boiling oil. Were the U.S. scientists simply to flip it back into the searing pitch? Rather than see the information fall into the hands of the Russians, the U.S. bargained with the Japanese officers responsible:immunity from war crime prosecution in exchange for the ill-gained data [source:McNaught]. The officers were even given stipends.

Similar concerns have arisen concerning Nazi documents leftover from the Holocaust. With no regard for the welfare of their test subjects, German scientists at Dachau subjected victims to extremely low temperatures -- often resulting in death. Yet the Nazis also used these experiments to determine the best method of reviving hypothermia patients in tubs of hot water. Hypothermia researchers later insisted that the data was valuable, no matter how deplorable the methods used to obtain it.

Many critics argue that by using the data, we validate the crimes. Yet purely logistical criticisms arise as well. Can we trust Nazi doctors who sought politically motivated results, such as those that "proved" German racial superiority? In many cases, the experiments lacked proper methods and protocol. The subjects themselves, selected from the death camps, tended to be imperfect specimens to begin with, already suffering from malnourishment and psychological trauma.

Sometimes, however, the victims of atrocity have managed to obtain useful data from the conditions brought on by their tormenters. Jewish doctors documented starvation in the Warsaw ghetto -- notes that later aided the study of hunger-associated disease [source:NOVA].

Experimenting on Unknowing Subjects

We tend to place a great deal of trust in our physicians. With that trust comes the understanding that they won't secretly experiment on us. But there was a time when entering a teaching hospital as a patient might result in not only the procedure you needed, but also whatever the students needed to practice that week [source:Roach].

While the prospect of receiving an unmerited appendectomy at no extra cost may seem horrifying enough, more shameful experiments litter medical history. In 1932, the U.S. Public Health Service began its 40-year Tuskegee study of syphilis. During this time, African-Americans who sought treatment for the disease were deceived. Instead of administering proper medical attention, the doctors allowed their conditions to worsen in order to better study the illness. The U.S. military also tested unsuspecting patients, exposing citizens to germ warfare agents and LSD in the '50s and '60s. Various U.S. radiological tests also used unknowing subjects, injecting hospital patients with plutonium and feeding radioactive cereal to mentally disabled children [source:Proquest].

Human trials became increasingly essential to the pharmaceutical industry as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration began requiring stricter testing of new drugs in the 1930s. In 1966, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) established the NIH Policy for Protection of Research Subjects. This measure established review boards to monitor human experimentation. To this day, U.S. colleges and universities that perform any kind of human experimentation also have institutional review boards , or IRBs .

Subsequently, the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research (later the President's Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research) entered the picture to refine the laws and practices surrounding human experimentation.

Throughout the 20th century, medical laws raced to keep pace with human experimentation -- often falling troublingly behind. For instance, 1964's Helsinki Declaration by the World Medical Association allowed for experimentation on incapacitated and incompetent individuals so long as legal guardians gave written consent.

Yet, even sheathed with the protection of signed written consent, human testing continues to bring up ethical concerns.

Modern Clinical Drug Trials

Walk into a Phase I U.S. clinical trial for a new drug and you'll likely find something between a frat house rec room and a hospital. Far from suffering, most of the test subjects would likely be busy watching TV or blasting through a few video games. As it turns out, catheters, needles and the occasional invasive surgical procedure don't really spoil a good time, especially when you're getting paid for it.

These mini-vacations for science can last anywhere from days to weeks and can pay in the thousands of dollars. Sometimes they're even held in hotel rooms. Phase I clinical trials typically involve otherwise healthy (though generally not gainfully employed) individuals. In this stage, researchers try to pinpoint dangerous side effects and potential complications. Phase II trials deal with dosing and efficiency, while Phase III trials enlist the help of actual patients to compare the experimental treatment to conventional ones, placebos or both.

A great deal of money and time go into these tests because pharmaceutical companies have a limited window to get a new drug out on the market and profit from it. U.S. drug patents only last 20 years; if a new medication is tied up in testing for a decade, then it will only have 10 moneymaking years left in it. While the companies themselves are frequently criticized for their commercialism, it does take a considerable financial investment to see a medical discovery all the way to the point where it can help patients -- even with limited or no human testing. Due to financial or logistical reasons, many potential medical breakthroughs don't even make it through the experimental period, which may be why researchers dub it "the valley of death."

Pharmaceutical companies used to rely more on university research facilities or teaching hospitals -- which, in turn, gave them access to students who might appreciate a spring break full of experimental psychotropic drugs and repeat viewings of "The Wall." The downside to this, however, was that it introduced academic bureaucracy into an already highly regulated process. The FDA required the tests to be supervised by an institutional review board, and these were generally staffed by university faculty.

To streamline this ordeal, pharmaceutical companies now deal largely with commercial contract research organizations , which handle all the testing. In a 2008 article in The New Yorker, Carl Elliot described the resulting situation as a subculture of guinea pigs -- they even have their own publications, detailing which studies have the best pay and perks.

Cash Money for Human Guinea Pigs

Paying human test subjects is a reality many view as unavoidable. While afflicted individuals might line up for the possible benefits of Phase III testing, Phase I testing tends to require healthy specimens. Like it or not, most of these individuals aren't going to volunteer without financial compensation.

This dilemma has existed for more than a century. In 1903, a New York physician stirred up ethical debate when he offered $5,000 to any man or woman willing to cut an ear off for his studies. Is it ethical to purchase a slice of another individual's health, even with the greater good in mind? Despite all the cozy accoutrements and oversight, paid test subjects put their health and even their lives on the line in sometimes painful or degrading clinical trials. After all, Phase I tests exist to help identify harmful side effects. If your bottle of medication says that it might result in bowel control problems or suicidal thoughts, you can bet that someone received a paycheck for experiencing them at some point.

Plus, there's the concern that the resulting guinea pig lifestyle winds up appealing to a particular segment of the general population. In some cases, the individuals are professional test subjects, moving from one to another like a jobless Phish fan trailing a never-ending tour. In other cases, the test ranks are occupied by some of the very underprivileged classes preyed upon in less ethical times:the poor, the mentally handicapped and even undocumented immigrants.

Contract research organizations have also come under fire for their oversight and staffing. University institutional review boards placed more emphasis on curtailing overzealous academics, in addition to testing ethics. For-profit review boards, however, answer to the market's need for speed, which has resulted in overlooked ethical concerns such as unsafe testing environments and unlicensed medical staff members. The FDA on the other hand largely places more emphasis on data inspections and reportedly inspects only 1 percent of clinical trials [source:Elliot].

Meanwhile, headlines continue to document the role of human embryonic stem cells in experimentation. While these highly versatile cells may play a huge role in the development of cures for various diseases and even ageing, many oppose the destruction of human embryos to get them.

In one form or another, human experimentation is as old as human curiosity. We learned that fire burned because we tested it. As scientific research continues, the challenge is to keep the flames in check.

Explore the links on the next page to learn even more about scientific experimentation.

Lots More Information

Related HowStuffWorks Articles

- How Biological and Chemical Warfare Works

- How Scientific Peer Review Works

- How the Scientific Method Works

- Are we on the brink of an AIDS vaccine?

- 10 Scariest Bioweapons

- How Stem Cells Work

More Great Links

- NOVA Online:The Holocaust on Trial

Sources

- "Ancient surgery:Alexandria." Channel 4. 2009. (March 17, 2009)http://www.channel4.com/history/microsites/H/history/a-b/ancientsurgery5.html

- Beagley, Sharon. "Where Are the Cures?" Newsweek. Nov. 10, 2008. (March 17, 2009)http://www.newsweek.com/id/166856

- Elliot, Carl. "Guinea-Pigging." The New Yorker. Jan. 1, 2008. (March 17, 2009)http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2008/01/07/080107fa_fact_elliott

- Harris, Eleanor. "Eight scientists who became their own guinea pigs." New Scientist. March 11, 2009. (March 17, 2009)http://www.newscientist.com/article/dn16735-eight-scientists-who-became-their-own-guinea-pigs.html?DCMP=OTC-rss&nsref=online-news

- Longrigg, James. "Greek Rationale Medicine." Routledge. 1992.http://books.google.com/books?id=qD6G9R_-1UMC&pg=PA190&lpg=PA190&dq=vivisection+alexandria+account&source=bl&ots=Dfu9t_cG5A&sig=xUSLDKWh3NwCSyV-CfZoQUkDWOk&hl=en&ei=rn26SdW4OdTFtgeDk-ziDw&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=1&ct=result#PPP1,M1

- Lunenfeld, Bruno, et al. "Textbook of Men's Health and Ageing:2nd Edition." CRC Press. 2008http://books.google.com/books?id=9vEeMOwKY4AC&pg=PA5&lpg=PA5&dq=San+Quentin+Prison+took+part+in+testicular+transplant+experiments&source=bl&ots=EXzW5JjQk8&sig=VaiYKGZGUWKVGnClpMz2-UDOg9c&hl=en&ei=GGi-SbWKCMi0tweww-z3Cw&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=10&ct=result#PPR12,M1

- "Medical Ethics Timeline." ProQuest. 2009.

- "Results of Death-Camp Experiments:Should They Be Used?" NOVA Online. October 2000. (March 17, 2009)http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/holocaust/experiments.html

- Roach, Mary. "Stiff:The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers." W.W. Norton &Company. 2003.

- Rodgers, Joann Ellison. "Guinea Pig Nation." Psychology Today. February 2009. (March 17, 2009)http://www.psychologytoday.com/articles/pto-20081215-000004.xml

- "Unit 731:Japan's biological force." BBC News. Feb. 1, 2002. (March 17, 2009)http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/programmes/correspondent/1796044.stm

Wat betekent pH in de chemie?

Wat betekent pH in de chemie?  Nieuw materiaal kan giftige stoffen uit de lucht opvangen

Nieuw materiaal kan giftige stoffen uit de lucht opvangen Moleculaire steiger voor het wijzigen van fluorescerende verbindingen die worden gebruikt in biologische beeldvorming

Moleculaire steiger voor het wijzigen van fluorescerende verbindingen die worden gebruikt in biologische beeldvorming Gluten in tarwe:wat is er veranderd in 120 jaar fokken?

Gluten in tarwe:wat is er veranderd in 120 jaar fokken? Zodra we de CO2-uitstoot kunnen opvangen, dit is wat we ermee kunnen doen

Zodra we de CO2-uitstoot kunnen opvangen, dit is wat we ermee kunnen doen

Hoofdlijnen

- Wat is het verschil tussen een gedupliceerd chromosoom en een chromaat?

- De schimmels onder zijn de grote ontbinders

- Zo'n 230 walvissen gestrand in Tasmanië; reddingspogingen aan de gang

- Verschillende populaties bosolifanten bijna instorten in Centraal-Afrika

- Waar is de kern gevonden in de cel en waarom?

- Hoeveel calorieën verbrand ik als ik lach?

- Het verschil tussen glycolyse en gluconeogenese

- Zelfbevruchtende vissen hebben een verrassende hoeveelheid genetische diversiteit

- Waarom zijn cellen belangrijk voor levende organismen?

- Onderzoek onthult de innerlijke werking van vloeibare kristallen

- Gemeenschappelijk kader voor het analyseren van complexe systemen in natuurkunde en economie

- Wetenschappers ontrafelen 70 jaar oud mysterie over hoe magnetische golven de zon verwarmen

- Transistors en diodes gemaakt van geavanceerde halfgeleidermaterialen zouden veel beter kunnen presteren dan silicium

- Triplet-supergeleiding aangetoond onder hoge druk

Arme kinderen falen door systeem op weg naar hoger onderwijs in lage-inkomenslanden

Arme kinderen falen door systeem op weg naar hoger onderwijs in lage-inkomenslanden Zwitserse statistische systemen verbeterd door big data

Zwitserse statistische systemen verbeterd door big data Europa heeft een koude en natte lente achter de rug, maar zal die de hele zomer duren?

Europa heeft een koude en natte lente achter de rug, maar zal die de hele zomer duren? Boornitride vernietigt voor altijd chemicaliën PFOA, GenX

Boornitride vernietigt voor altijd chemicaliën PFOA, GenX Ternaire acceptor- en donormaterialen verhogen de fotonenoogst in organische zonnecellen

Ternaire acceptor- en donormaterialen verhogen de fotonenoogst in organische zonnecellen Verkeerde identiteit:een veronderstelde supernova is eigenlijk iets veel zeldzamer

Verkeerde identiteit:een veronderstelde supernova is eigenlijk iets veel zeldzamer De voordelen van potentiometrische titratie

De voordelen van potentiometrische titratie  Navigeren door het AI-doolhof is een uitdaging voor overheden

Navigeren door het AI-doolhof is een uitdaging voor overheden

- Elektronica

- Biologie

- Zonsverduistering

- Wiskunde

- French | Italian | Spanish | Portuguese | Swedish | German | Dutch | Danish | Norway |

-

Wetenschap © https://nl.scienceaq.com