Wetenschap

Supergeleidende röntgenlaser bereikt bedrijfstemperatuur die kouder is dan de ruimte

Krediet:SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

Genesteld 9 meter onder de grond in Menlo Park, Californië, is een 800 meter lang stuk tunnel nu kouder dan het grootste deel van het universum. Het herbergt een nieuwe supergeleidende deeltjesversneller, onderdeel van een upgradeproject voor de Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) röntgenvrije elektronenlaser in het SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory van het Department of Energy.

Bemanningen hebben de versneller met succes afgekoeld tot min 456 graden Fahrenheit - of 2 Kelvin - een temperatuur waarbij het supergeleidend wordt en elektronen kan stimuleren tot hoge energieën met bijna nul energieverlies in het proces. Het is een van de laatste mijlpalen voordat LCLS-II röntgenpulsen zal produceren die gemiddeld 10.000 keer helderder zijn dan die van LCLS en die tot een miljoen keer per seconde aankomen - een wereldrecord voor de krachtigste röntgenpulsen van vandaag. straallichtbronnen.

"In slechts een paar uur zal LCLS-II meer röntgenpulsen produceren dan de huidige laser in zijn hele leven heeft gegenereerd", zegt Mike Dunne, directeur van LCLS. "Gegevens die vroeger maanden nodig hadden om te verzamelen, kunnen in enkele minuten worden geproduceerd. Het zal de röntgenwetenschap naar een hoger niveau tillen, de weg vrijmaken voor een hele nieuwe reeks onderzoeken en ons vermogen om revolutionaire technologieën te ontwikkelen om een aantal van de de grootste uitdagingen voor onze samenleving."

Met deze nieuwe mogelijkheden kunnen wetenschappers de details van complexe materialen onderzoeken met een ongekende resolutie om nieuwe vormen van computergebruik en communicatie te stimuleren; zeldzame en vluchtige chemische gebeurtenissen onthullen om ons te leren hoe we duurzamere industrieën en schone energietechnologieën kunnen creëren; bestuderen hoe biologische moleculen de functies van het leven uitvoeren om nieuwe soorten geneesmiddelen te ontwikkelen; en neem een kijkje in de bizarre wereld van de kwantummechanica door de bewegingen van individuele atomen rechtstreeks te meten.

Een huiveringwekkende prestatie

LCLS, 's werelds eerste harde röntgenvrije-elektronenlaser (XFEL), produceerde zijn eerste licht in april 2009 en genereerde röntgenpulsen die een miljard keer helderder waren dan alles wat daarvoor was verschenen. Het versnelt elektronen door een koperen pijp bij kamertemperatuur, wat de snelheid beperkt tot 120 röntgenpulsen per seconde.

In 2013, SLAC launched the LCLS-II upgrade project to boost that rate to a million pulses and make the X-ray laser thousands of times more powerful. For that to happen, crews removed part of the old copper accelerator and installed a series of 37 cryogenic accelerator modules, which house pearl-like strings of niobium metal cavities. These are surrounded by three nested layers of cooling equipment, and each successive layer lowers the temperature until it reaches nearly absolute zero—a condition at which the niobium cavities become superconducting.

"Unlike the copper accelerator powering LCLS, which operates at ambient temperature, the LCLS-II superconducting accelerator operates at 2 Kelvin, only about 4 degrees Fahrenheit above absolute zero, the lowest possible temperature," said Eric Fauve, director of the Cryogenic Division at SLAC. "To reach this temperature, the linac is equipped with two world-class helium cryoplants, making SLAC one of the significant cryogenic landmarks in the U.S. and on the globe. The SLAC Cryogenics team has worked on site throughout the pandemic to install and commission the cryogenic system and cool down the accelerator in record time."

One of these cryoplants, built specifically for LCLS-II, cools helium gas from room temperature all the way down to its liquid phase at just a few degrees above absolute zero, providing the coolant for the accelerator.

On April 15, the new accelerator reached its final temperature of 2 K for the first time and today, May 10, the accelerator is ready for initial operations.

"The cooldown was a critical process and had to be done very carefully to avoid damaging the cryomodules," said Andrew Burrill, director of SLAC's Accelerator Directorate. "We're excited that we've reached this milestone and can now focus on turning on the X-ray laser."

Bringing it to life

In addition to a new accelerator and a cryoplant, the project required other cutting-edge components, including a new electron source and two new strings of undulator magnets that can generate both "hard" and "soft" X-rays. Hard X-rays, which are more energetic, allow researchers to image materials and biological systems at the atomic level. Soft X-rays can capture how energy flows between atoms and molecules, tracking chemistry in action and offering insights into new energy technologies. To bring this project to life, SLAC teamed up with four other national labs—Argonne, Berkeley Lab, Fermilab and Jefferson Lab—and Cornell University.

Jefferson Lab, Fermilab and SLAC pooled their expertise for research and development on cryomodules. After constructing the cryomodules, Fermilab and Jefferson Lab tested each one extensively before the vessels were packed and shipped to SLAC by truck. The Jefferson Lab team also designed and helped procure the elements of the cryoplants.

"The LCLS-II project required years of effort from large teams of technicians, engineers and scientists from five different DOE laboratories across the U.S. and many colleagues from around the world," says Norbert Holtkamp, SLAC deputy director and the project director for LCLS-II. "We couldn't have made it to where we are now without these ongoing partnerships and the expertise and commitment of our collaborators."

Toward first X-rays

Now that the cavities have been cooled, the next step is to pump them with more than a megawatt of microwave power to accelerate the electron beam from the new source. Electrons passing through the cavities will draw energy from the microwaves so that by the time the electrons have passed through all 37 cryomodules, they'll be moving close to the speed of light. Then they'll be directed through the undulators, forcing the electron beam on a zigzag path. If everything is aligned just right—to within a fraction of the width of a human hair—the electrons will emit the world's most powerful bursts of X-rays.

This is the same process that LCLS uses to generate X-rays. However, since LCLS-II uses superconducting cavities instead of warm copper cavities based on 60-year-old technology, it can can deliver up to a million pulses per second, 10,000 times the number of X-ray pulses for the same power bill.

Once LCLS-II produces its first X-rays, which is expected to happen later this year, both X-ray lasers will work in parallel, allowing researchers to conduct experiments over a wider energy range, capture detailed snapshots of ultrafast processes, probe delicate samples and gather more data in less time, increasing the number of experiments that can be performed. It will greatly expand the scientific reach of the facility, allowing scientists from across the nation and around the world to pursue the most compelling research ideas. + Verder verkennen

Upgraded X-ray laser shows its soft side

Wetenschapsprojecten over keukenchemie

Wetenschapsprojecten over keukenchemie  Zonnecellen met nieuwe interfaces

Zonnecellen met nieuwe interfaces Nieuwe structurele details over de specifieke rangschikking van atomen in geconjugeerde polymeren

Nieuwe structurele details over de specifieke rangschikking van atomen in geconjugeerde polymeren Akoestisch microfluïdisch platform scheidt circulerende tumorcellen voorzichtig en snel van bloedmonsters

Akoestisch microfluïdisch platform scheidt circulerende tumorcellen voorzichtig en snel van bloedmonsters Zuurstofbleken versus Chloor Bleach

Zuurstofbleken versus Chloor Bleach

Seismogrammen vóór de uitbarsting hersteld voor het Mount St. Helens-evenement in 1980

Seismogrammen vóór de uitbarsting hersteld voor het Mount St. Helens-evenement in 1980 Sommige droogteperiodes tijdens de Indiase moesson zijn te wijten aan unieke verstoringen in de Noord-Atlantische Oceaan

Sommige droogteperiodes tijdens de Indiase moesson zijn te wijten aan unieke verstoringen in de Noord-Atlantische Oceaan Onderzoek naar de betekenis van oude geometrische grondwerken in het zuidwesten van Amazonië

Onderzoek naar de betekenis van oude geometrische grondwerken in het zuidwesten van Amazonië Naschokken rammelen aardbeving getroffen Kreta als Griekse premier om te bezoeken

Naschokken rammelen aardbeving getroffen Kreta als Griekse premier om te bezoeken Gevaarlijke hittegolven zullen de tropen waarschijnlijk dagelijks teisteren tegen 2100:studie

Gevaarlijke hittegolven zullen de tropen waarschijnlijk dagelijks teisteren tegen 2100:studie

Hoofdlijnen

- "3-D Printing Goes Cellular

- Neteldieren controleren bacteriën op afstand

- Onderzoek naar plantenenzymen toont aan dat eiwitten hun structurele rangschikking met verrassend gemak kunnen veranderen

- Een AI-berichtendecoder op basis van bacteriegroeipatronen

- Beren hebben geen last van een dieet met veel verzadigde vetten

- Motivaties voor het jagen op dieren in het wild variëren in Afrika en Europa

- Woestijn in Zuid-Californië overspoeld met de beste superbloei in 20 jaar

- Wat zijn de stadia van de celcyclus?

- Waarom zouden wetenschappers een hybride mens-koe-embryo willen creëren?

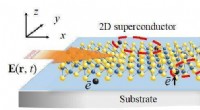

- Een scanning quantum sensing microscoop met elektrische veldbeeldvorming op nanoschaal

- Supergeleiders aansturen met licht

- Hoe antivries-eiwitten ijskoud stoppen

- CUORE-experiment beperkt neutrino-eigenschappen

- Luchtgeleiding in optische golfgeleiders met vaste kern:een oplossing voor on-chip spoorgasspectroscopie

NASA vindt tropische storm Saola's kracht uit het midden

NASA vindt tropische storm Saola's kracht uit het midden Studie:de meeste Amerikanen geloven niet dat minder discriminatie van zwarten meer betekent tegen blanken

Studie:de meeste Amerikanen geloven niet dat minder discriminatie van zwarten meer betekent tegen blanken De coolste LEGO in het universum

De coolste LEGO in het universum Sterkste tornado in 8 decennia treft Cuba; 3 doden, 172 pijn

Sterkste tornado in 8 decennia treft Cuba; 3 doden, 172 pijn Robots kunnen een revolutie teweegbrengen in de monitoring van het mariene milieu

Robots kunnen een revolutie teweegbrengen in de monitoring van het mariene milieu Marshall eilanden, laaggelegen bondgenoot van de VS en nucleaire testlocatie, verklaart een klimaatcrisis

Marshall eilanden, laaggelegen bondgenoot van de VS en nucleaire testlocatie, verklaart een klimaatcrisis Onderzoek werpt licht op de impact van verzekeringsuitkeringen na rampen

Onderzoek werpt licht op de impact van verzekeringsuitkeringen na rampen Verrassende ontdekking in de zoektocht naar energie-efficiënte informatieopslag

Verrassende ontdekking in de zoektocht naar energie-efficiënte informatieopslag

- Elektronica

- Biologie

- Zonsverduistering

- Wiskunde

- French | Italian | Spanish | Portuguese | Swedish | German | Dutch | Danish | Norway |

-

Wetenschap © https://nl.scienceaq.com