Wetenschap

Moderne alchemisten maken scheikunde groener

Oude alchemisten probeerden lood en andere gewone metalen om te zetten in goud en platina. Moderne scheikundigen in het laboratorium van Paul Chirik in Princeton transformeren reacties die afhankelijk waren van milieuonvriendelijke edelmetalen, goedkopere en groenere alternatieven vinden om platina te vervangen, rhodium en andere edele metalen bij de productie van geneesmiddelen en andere reacties.

Ze hebben een revolutionaire aanpak gevonden waarbij kobalt en methanol worden gebruikt om een medicijn tegen epilepsie te produceren waarvoor voorheen rhodium en dichloormethaan nodig waren. een giftig oplosmiddel. Hun nieuwe reactie werkt sneller en goedkoper, en het heeft waarschijnlijk een veel kleinere impact op het milieu, zei Chirik, de Edwards S. Sanford hoogleraar scheikunde. "Dit benadrukt een belangrijk principe in groene chemie - dat de meer milieuvriendelijke oplossing ook chemisch de voorkeur kan hebben, " zei hij. Het onderzoek is gepubliceerd in het tijdschrift Wetenschap op 25 mei.

"Farmaceutische ontdekking en proces omvatten allerlei exotische elementen, " zei Chirik. "We zijn misschien 10 jaar geleden met dit programma begonnen, en het was echt gemotiveerd door de kosten. Metalen zoals rhodium en platina zijn erg duur, maar naarmate het werk evolueerde, we realiseerden ons dat er veel meer bij komt kijken dan alleen prijsstelling. ... Er zijn enorme milieuproblemen, als je erover nadenkt om platina uit de grond te graven. Typisch, je moet ongeveer anderhalve kilometer diep gaan en 10 ton aarde verplaatsen. Dat heeft een enorme CO2-voetafdruk."

Chirik en zijn onderzoeksteam werkten samen met chemici van Merck &Co., Inc., om milieuvriendelijkere manieren te vinden om de materialen te maken die nodig zijn voor de moderne medicijnchemie. De samenwerking is mogelijk gemaakt door het Grant Opportunities for Academic Liaison with Industry (GOALI)-programma van de National Science Foundation.

Een lastig aspect is dat veel moleculen rechts- en linkshandige vormen hebben die verschillend reageren, met soms gevaarlijke gevolgen. De Food and Drug Administration heeft strikte vereisten om ervoor te zorgen dat medicijnen slechts één "hand" tegelijk hebben, bekend als geneesmiddelen met één enantiomeer.

"Chemici worden uitgedaagd om methoden te ontdekken om slechts één hand van medicijnmoleculen te synthetiseren in plaats van beide te synthetiseren en vervolgens te scheiden, " zei Chirik. "Metaalkatalysatoren, historisch gebaseerd op edele metalen zoals rhodium, hebben de opdracht gekregen om deze uitdaging op te lossen. Ons artikel laat zien dat een meer aarderijk metaal, kobalt, kan worden gebruikt om het epilepsiemedicijn Keppra als slechts één hand te synthetiseren."

Vijf jaar geleden, onderzoekers in het laboratorium van Chirik hebben aangetoond dat kobalt organische moleculen met één enantiomeer kan maken, maar alleen met relatief eenvoudige en niet medicinaal actieve verbindingen - en met behulp van giftige oplosmiddelen.

"We waren geïnspireerd om onze demonstratie van principe in praktijkvoorbeelden te duwen en aan te tonen dat kobalt beter zou kunnen presteren dan edele metalen en zou kunnen werken onder milieuvriendelijkere omstandigheden, " zei hij. Ze ontdekten dat hun nieuwe op kobalt gebaseerde techniek sneller en selectiever is dan de gepatenteerde rhodiumbenadering.

"Ons artikel toont een zeldzaam geval aan waarin een aardrijk overgangsmetaal de prestaties van een edelmetaal kan overtreffen bij de synthese van geneesmiddelen met één enantiomeer, " zei hij. "Waar we naar beginnen over te gaan, is dat de aarde-overvloedige katalysatoren niet alleen de edelmetalen vervangen, maar ze bieden duidelijke voordelen, of het nu gaat om nieuwe chemie die nog nooit iemand heeft gezien, of het gaat om verbeterde reactiviteit of een kleinere ecologische voetafdruk."

Niet alleen zijn onedele metalen goedkoper en veel milieuvriendelijker dan zeldzame metalen, maar de nieuwe techniek werkt in methanol, wat veel groener is dan de gechloreerde oplosmiddelen die rhodium nodig heeft.

"De vervaardiging van medicijnmoleculen, vanwege hun complexiteit, is one of the most wasteful processes in the chemical industry, " said Chirik. "The majority of the waste generated is from the solvent used to conduct the reaction. The patented route to the drug relies on dichloromethane, one of the least environmentally friendly organic solvents. Our work demonstrates that Earth-abundant catalysts not only operate in methanol, a green solvent, but also perform optimally in this medium.

"This is a transformative breakthrough for Earth-abundant metal catalysts, as these historically have not been as robust as precious metals. Our work demonstrates that both the metal and the solvent medium can be more environmentally compatible."

Methanol is a common solvent for one-handed chemistry using precious metals, but this is the first time it has been shown to be useful in a cobalt system, noted Max Friedfeld, the first author on the paper and a former graduate student in Chirik's lab.

Cobalt's affinity for green solvents came as a surprise, said Chirik. "For a decade, catalysts based on Earth-abundant metals like iron and cobalt required very dry and pure conditions, meaning the catalysts themselves were very fragile. By operating in methanol, not only is the environmental profile of the reaction improved, but the catalysts are much easier to use and handle. This means that cobalt should be able to compete or even outperform precious metals in many applications that extend beyond hydrogenation."

The collaboration with Merck was key to making these discoveries, noted the researchers.

Chirik said:"This is a great example of an academic-industrial collaboration and highlights how the very fundamental—how do electrons flow differently in cobalt versus rhodium?—can inform the applied—how to make an important medicine in a more sustainable way. I think it is safe to say that we would not have discovered this breakthrough had the two groups at Merck and Princeton acted on their own."

The key was volume, said Michael Shevlin, an associate principal scientist at the Catalysis Laboratory in the Department of Process Research &Development at Merck &Co., Inc., and a co-author on the paper.

"Instead of trying just a few experiments to test a hypothesis, we can quickly set up large arrays of experiments that cover orders of magnitude more chemical space, " Shevlin said. "The synergy is tremendous; scientists like Max Friedfeld and [co-author and graduate student] Aaron Zhong can conduct hundreds of experiments in our lab, and then take the most interesting results back to Princeton to study in detail. What they learn there then informs the next round of experimentation here."

Chirik's lab focuses on "homogenous catalysis, " the term for reactions using materials that have been dissolved in industrial solvents.

"Homogenous catalysis is usually the realm of these precious metals, the ones at the bottom of the periodic table, " Chirik said. "Because of their position on the periodic table, they tend to go by very predictable electron changes—two at a time—and that's why you can make jewelry out of these elements, because they don't oxidize, they don't interact with oxygen. So when you go to the Earth-abundant elements, usually the ones on the first row of the periodic table, the electronic structure—how the electrons move in the element—changes, and so you start getting one-electron chemistry, and that's why you see things like rust for these elements.

Chirik's approach proposes a radical shift for the whole field, said Vy Dong, a chemistry professor at the University of California-Irvine who was not involved in the research. "Traditional chemistry happens through what they call two-electron oxidations, and Paul's happens through one-electron oxidation, " she said. "That doesn't sound like a big difference, but that's a dramatic difference for a chemist. That's what we care about—how things work at the level of electrons and atoms. When you're talking about a pathway that happens via half of the electrons that you'd normally expect, it's a big deal. ... That's why this work is really exciting. You can imagine, once we break free from that mold, you can start to apply it to other things, te."

"We're working in an area of the periodic table where people haven't, for a long time, so there's a huge wealth of new fundamental chemistry, " said Chirik. "By learning how to control this electron flow, the world is open to us."

High-definition in kaart brengen van vocht in de bodem

High-definition in kaart brengen van vocht in de bodem NASA vindt potentieel voor zware regenval in nieuwe tropische cycloon Pola

NASA vindt potentieel voor zware regenval in nieuwe tropische cycloon Pola Aanpassing aan klimaatverandering vereist inheemse kennis

Aanpassing aan klimaatverandering vereist inheemse kennis NASA vindt sterkste stormen in nieuw gevormde tropische cycloon 13P

NASA vindt sterkste stormen in nieuw gevormde tropische cycloon 13P 70% van Californië zit officieel in een droogte. Hier zijn enkele huishoudelijke tips om water te besparen

70% van Californië zit officieel in een droogte. Hier zijn enkele huishoudelijke tips om water te besparen

Hoofdlijnen

- Moet je intelligent zijn om slecht te zijn?

- Zalmen helpen hun nakomelingen door te sterven op de paaigronden

- Genbewerking in de hersenen krijgt een grote upgrade

- Geslachtsrollen in de oudheid

- Wat gebeurt er met een Zygote na de bevruchting?

- Hoe telomeren werken

- Kenmerken van micro-organismen

- Wetenschappers ontdekken patronen van olifantenstroperij in Oost-Afrika

- De virale parasieten van gigantische virussen in de loop van de tijd volgen

- Wetenschappers ontwikkelen sondes om acuut nierfalen vroegtijdig te detecteren

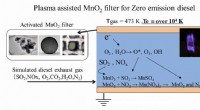

- Emissievrije dieselverbranding met een niet-evenwichtsplasma-ondersteund MnO2-filter

- Kenmerken van Plasmas

- Doorbraak in onderzoek naar schone diesel

- Nieuwe solid-state thermische diode ontwikkeld met betere rectificatieprestaties

Compilatie van onderzoek naar PFAS in het milieu

Compilatie van onderzoek naar PFAS in het milieu Welke dieren eten planten en dieren?

Welke dieren eten planten en dieren?

Een dier dat zowel planten als andere dieren eet, is geclassificeerd als een alleseter. Er zijn twee soorten alleseters; diegenen die op jacht prooien: zoals herbivoren en andere omnivoren, en degenen die speure

Splitsende kristallen voor 2-D metalen geleidbaarheid

Splitsende kristallen voor 2-D metalen geleidbaarheid Voordelen en nadelen van hydraulische systemen

Voordelen en nadelen van hydraulische systemen Hoe bruine spiders te identificeren

Hoe bruine spiders te identificeren  Katalysatoren voor isotactische polaire polypropylenen

Katalysatoren voor isotactische polaire polypropylenen Big data en machine learning inzetten om bosbranden in het westen van de VS te voorspellen

Big data en machine learning inzetten om bosbranden in het westen van de VS te voorspellen Waarom Irma zo sterk is en andere vragen over orkanen

Waarom Irma zo sterk is en andere vragen over orkanen

- Elektronica

- Biologie

- Zonsverduistering

- Wiskunde

- French | Italian | Spanish | Portuguese | Swedish | German | Dutch | Danish | Norway |

-

Wetenschap © https://nl.scienceaq.com