Wetenschap

De verdwijnende banen van gisteren

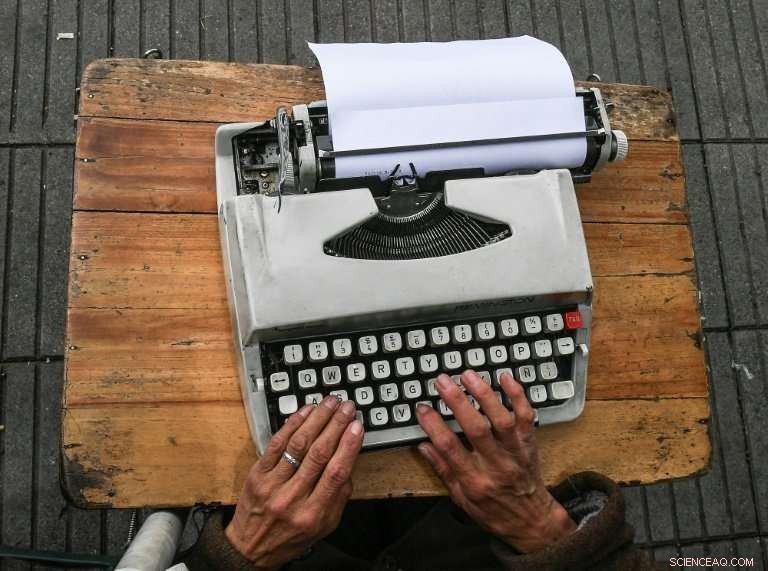

Colombiaanse straatklerken werken in de open lucht door met hun typemachines op een klein tafeltje voor hen

Voorafgaand aan de meidag, AFP-verslaggevers, video- en fototeams spraken met mannen en vrouwen over de hele wereld wier banen steeds zeldzamer worden, vooral omdat technologie samenlevingen transformeert.

De laatste straatklerken van Bogota

Een blanco vel in haar Remington Sperry stoppen, Candelaria Pinilla de Gomez begint te typen. Een van Bogota's straatklerken, ze heeft de afgelopen 40 jaar ontelbare duizenden documenten getypt.

63 jaar oud, zij is de enige vrouw onder de straatklerken die hun kleine tafeltjes op de stoep hebben gezet voor een modern kantoorgebouw in Bogota.

Kostuums dragen, maar geen stropdassen, de schrijvers werken in de open lucht, onder een parasol, zittend op een plastic stoel met de typemachine op hun knieën.

Er was eens, deze griffiers speelden een essentiële rol - met openbare akten, belastingdocumenten en contracten die allemaal door hun handen gaan.

Pinilla de Gomez leerde het vak van haar man toen ze in de jaren zestig in de Colombiaanse hoofdstad aankwamen. Hij had een boerderij "maar de guerrilla's namen het van hem af, " ze zegt.

"In Bogota, hij zei dat ik moest leren typen... en spellen. Hij leerde me (de baan) en toen stierf hij."

Cesar Díaz, nu 68, gaat er prat op de pionier te zijn van een vak dat uiteindelijk een "toevluchtsoord" is geworden voor gepensioneerden die hun maandelijkse toelagen willen aanvullen.

Candelaria Pinilla de Gomez, 63, werkt al zo'n 40 jaar als straatklerk in Bogota

Ze werken van maandag tot vrijdag en verdienen minder dan $ 280, wat het minimumloon is.

Tot nu, ze zijn erin geslaagd om vrijwel alles te overleven, behalve misschien de komst van internet.

"Tegenwoordig, een moeder zal haar zoon vragen een formulier te downloaden, vul het in en verstuur het via internet, " geeft Pinilla de Gomez toe.

"Dat verpest het echt voor ons."

— Foto's door Luis Acosta. Video door Juan Restrepo

Wasvrouwen, hun handel verdwijnt als zeep in water

De handen van Delia Veloz hebben bijna hun vingerafdrukken verloren door de constante ritmische beweging van het wrijven van vuile kleren tegen ruwe stenen bij een oude openbare wasserij in Quito.

Met een dweil van krullende grijze krullen, deze 74-jarige is een van de weinige mensen in Ecuador die nog steeds het oude en veeleisende werk van een wasvrouw beoefent - een vak dat steeds zeldzamer wordt vanwege het wijdverbreide gebruik van huishoudelijke wasmachines.

Wu Chi-kai buigt glazen buizen die van binnen met fluorescerend poeder zijn bestoven in vorm boven een krachtige gasbrander

"Ik hou niet van wasmachines, ze wassen niet zo goed. Met de hand kun je dingen beter schrobben, " vertelt Veloz trots aan AFP terwijl ze een pot ijskoud water uit de Andes over een jas giet.

Al meer dan vijf decennia werkt ze bij de Ermita, een openbare wasserij in het koloniale centrum van Quito met haar rechthoekige steen, tank met water en verschillende draden om dingen te drogen te hangen.

Voor elke 12 kledingstukken, ze verdient 1,50 dollar (1,20 euro) van haar steeds schaarser wordende klanten - vooral degenen die geen wasmachine hebben of die dingen liever met de hand wassen.

Op een goede dag, ze kan tussen $ 3 en $ 6 verdienen.

in Quito, er zijn nog minstens vijf openbare wasserijen die in de eerste helft van de 20e eeuw werden gebouwd.

Er zijn ook mensen die de was komen gebruiken om hun eigen kleren te wassen of die van hun werkgevers - waarvoor geen kosten zijn.

En een keer per maand, ze komen allemaal samen om het pand netjes en opgeruimd te houden.

— Foto's door Rodrigo Buendia

Neon is het stedelijke landschap in Hong Kong gaan bepalen, met enorme knipperende borden die horizontaal uit de zijkanten van gebouwen steken

Waterboys beginnen droog te worden

Het gebrek aan stromend water in de armste wijken van Kenia heeft de laatste 18 jaar, betekende de kost voor Simson Muli, een waterverkoper in de sloppenwijk Kibera in Nairobi.

"Toen ik opgroeide, wilde ik zakenman worden, " zegt de 42-jarige vader van twee, die water levert aan slagers, visverkopers en restaurants op de overvolle Kenyatta-markt.

Gekleed in een dunne stofjas gebruikt Muli een slang om zijn reeks cilindrische jerrycans van 20 liter te vullen met water uit drie vrijstaande 10, 000 liter tanks. Hij laadt er 15 tegelijk op een karretje, en sleept ze naar zijn klanten.

The margins are tiny—Muli buys water at five shillings ($0.05) a can and sells for 15—but it can add up to 1, 000 shillings a day, enough to make a difference.

"This job has changed my life because my children are able to go to school and I am able to afford to pay school fees for them, " hij zegt.

But Kenya's gradual development and the spreading provision of basic infrastructure, including piped water, means Muli's profitable days are numbered.

— Pictures by Simon Maina. Video by Raphael Ambasu

Chi-kai works without a safety visor and has been scalded and cut by glass which sometimes cracks and explodes

Rickshaw pullers fade from India's streets

Mohammad Maqbool Ansari puffs and sweats as he pulls his rickshaw through Kolkata's teeming streets, a veteran of a gruelling trade long outlawed in most parts of the world and slowly fading from India too.

Kolkata is one of the last places on earth where pulled rickshaws still feature in daily life, but Ansari is among a dying breed still eking a living from this back-breaking labour.

The 62-year-old has been pulling rickshaws for nearly four decades, hauling cargo and passengers by hand in drenching monsoon rains and stifling heat that envelops India's heaving eastern metropolis.

Their numbers are declining as pulled rickshaws are relegated to history, usurped by tuk tuks, Kolkata's famous yellow taxis and modern conveniences like Uber.

Ansari cannot imagine life for Kolkata's thousands of rickshaw-wallahs if the job ceased to exist.

"If we don't do it, how will we survive? We can't read or write. We can't do any other work. Once you start, that's it. This is our life, " he tells AFP.

Sweating profusely on a searing-hot day, his singlet soaked and face dripping, Ansari skilfully weaved his rickshaw through crowded markets and bumper to bumper traffic.

Venezuelan darkroom technician Rodrigo Benavides refuses to go digital

Wearing simple shoes and a chequered sarong, the only real giveaway of his age is a long beard, snow white and frizzy, and a face weathered from a lifetime plying this trade.

Twenty minutes later, he stops, wiping his face on a rag. The passenger offers him a glass of water—a rare blessing—and hands a bill over.

"When it's hot, for a trip that costs 50 rupees ($0.75) I'll ask for an extra 10 rupees. Some will give, some don't, " hij zegt.

"But I'm happy with being a rickshaw puller. I'm able to feed myself and my family."

— Pictures by Dibyangshu Sarkar. Video by Atish Patel

Hong Kong's neon nostalgia

Neon sign maker Wu Chi-kai is one of the last remaining craftsmen of his kind in Hong Kong, a city where darkness never really falls thanks to the 24-hour glow of myriad lights.

During his 30 years in the business, neon came to define the urban landscape, huge flashing signs protruding horizontally from the sides of buildings, advertising everything from restaurants to mahjong parlours.

Although working with equipment and techniques that have virtually disappeared, he carries on as if digital photography does not exist

But with the growing popularity of brighter LED lights, seen as easier to maintain and more environmentally friendly, and government orders to remove some vintage signs deemed dangerous, the demand for specialists like Chi-kai has dimmed.

Despite a waning client-base, the 50-year-old continues in the trade, working with glass tubes dusted inside with fluorescent powder and containing various gases including neon or argon, as well as mercury, to create different colours.

He bends them into shape over a powerful gas burner at a scorching 1, 000 degrees Celsius.

"Being able to twist straight glass materials into the shape I want, and later to make it glow—it's quite fun, " zegt hij tegen AFP, though it is not without risks.

Chi-kai works without a safety visor and has been scalded and cut by glass which sometimes cracks and explodes.

"The painful experiences are the memorable ones, " he adds philosophically.

His father used to scale Hong Kong's famous bamboo scaffolding while installing neon signs across the city.

Believing the installation work too dangerous for his son, he instead encouraged him to learn to make the signs as a teenager. Chi-kai became one of only around 30 masters of the craft in Hong Kong, even in neon's heyday.

Using his bathroom as a makeshift lab, he develops negatives, turning them into black and white prints

Although demand is now significantly lower than at neon's peak in the 1980s, hij zegt, there has been renewed interest and nostalgia for its gentler glow, immortalised in the atmospheric movies of award-winning Hong Kong director Wong Kar-wai.

Some of Chi-kai's clients are now requesting pieces for indoor decoration.

"I've been working with neon lights all my life. I can't think of anything else I'd be better suited for, " hij zegt.

— Pictures by Philip Fong. Video by Diana Chan

Developing film as if digital didn't exist

With an ancient 50-year-old Olympus camera and an enlarger that he bought in 1980, Venezuelan photographer Rodrigo Benavides works his "magic" inside a tiny improvised darkroom at home.

Although working with equipment and techniques that have virtually disappeared, he carries on as if digital photography doesn't exist.

"Doesn't interest me at all, " hij zegt.

Er was eens, these clerks played an essential role—with public deeds, tax documents and contracts all passing through their hands

Using his bathroom as a makeshift lab, he develops negatives, turning them into black and white prints. And it still fascinates him every time as the image slowly emerges on coming in to contact with the chemicals.

"I have always tried to be economical with my resources, always have done, always will do, " hij zegt, extolling the wonders of his Olympus 35 SP which uses a reel of film, doesn't need batteries and is completely manual.

Born in Caracas 58 years ago, he still remembers the excitement when, at the age of 19, he bought the enlarger in London.

And it was there that he became a keen follower of Group f/64, an influential movement of photographers who championed sharp-focused, unretouched images of natural subjects.

He thinks technology has "upended" photography, turning it into a work of "fiction."

"We have become desensitised to reality, which is much more interesting than fiction, " hij zegt.

Some 400 of his pictures taken over 30 years have been compiled into a book on the Venezuelan plains. Others are stacked up in his living room, forming a towering pile, some two meters high.

"They are like my children, " says Benavides, who describes himself as a documentary photographer practising a trade on the verge of extinction.

-

Delia Veloz, 74, is one of the few people left in Ecuador who still practises the ancient and demanding work of a washerwoman

-

Washerwomen rub dirty clothes against rough stones at an old public laundry in Quito

-

In Quito, there are still at least five public laundries which were built in the first half of the 20th century

-

The lack of running water in Kenya's poorest neighbourhoods has meant a living for Samson Muli, a water seller in Nairobi's Kibera slum

-

Waterboys supply water to butchers, fishmongers and restaurants in the crowded Kenyatta market

-

Kolkata is one of the last places on earth where pulled rickshaws still feature in daily life

-

Mohammad Ashgar is one of the remaining Indian rickshaw pullers undertaking the gruelling trade

© 2018 AFP

De uitkomst van de wapenwedloop tussen mens en bacterie voorspellen

De uitkomst van de wapenwedloop tussen mens en bacterie voorspellen Wat is de chemische formule van bleekmiddel?

Wat is de chemische formule van bleekmiddel?

Bleach is de algemene term voor stoffen die vlekken oxideren of "bleken". Er zijn een aantal in de handel verkrijgbare bleekverbindingen. Ze worden allemaal gebruikt om het wasgoed te ontsmetten en op te

Het potentieel van metalen nanodeeltjes als katalysatoren voor snelle en efficiënte CO2-omzetting ontsluiten

Het potentieel van metalen nanodeeltjes als katalysatoren voor snelle en efficiënte CO2-omzetting ontsluiten Wat zijn de eigenschappen van protonen?

Wat zijn de eigenschappen van protonen?  Wat is een Cul Ionische verbinding?

Wat is een Cul Ionische verbinding?

Hoofdlijnen

- Wat zijn de drie belangrijkste verschillen tussen een plantencel en een dierencel?

- NASA Twins-onderzoek wordt gerepliceerd op Everest

- Hoe een 3D-model voor celbiologieprojecten te bouwen Mitochondria & Chloroplast

- Scented Cleaning Products: The New Smoking?

- Eenvoudige manieren om de structuren van de Skull

- Bodembedekkers verhogen de vernietiging van onkruidzaden in velden, licht werpen op interacties met roofdieren

- De ongelooflijke reis van de eerste Afrikaanse schildpad die in Europa aankwam

- De reden voor het kleuren van een monster op de microscoop

- Het ochtendkoor horen:Okina was een nieuw akoestisch monitoringnetwerk

- Pi is berekend tot 31,4 biljoen decimalen, Google kondigt op Pi-dag aan

- Amazon biedt op 60% belang in Indias Flipkart:rapport

- Fitness-app onthulde gegevens over militaire, inlichtingenpersoneel

- Facebook gaat advertenties met ansichtkaarten verifiëren na Russische inmenging (update)

- IOS 13:13 verborgen manieren waarop de nieuwe software van Apple je verouderde iPhone tot leven kan brengen

Studie onthult essentiële ingrediënten voor groei van nanodraad

Studie onthult essentiële ingrediënten voor groei van nanodraad Bewijs opgraven voor de oorsprong van platentektoniek

Bewijs opgraven voor de oorsprong van platentektoniek Natuurkundigen creëren tijdkristallen:nieuwe vorm van materie kan de sleutel zijn tot de ontwikkeling van kwantummachines

Natuurkundigen creëren tijdkristallen:nieuwe vorm van materie kan de sleutel zijn tot de ontwikkeling van kwantummachines Waarom hebben we nog steeds offshore oliebronnen? Hoe werken ze?

Waarom hebben we nog steeds offshore oliebronnen? Hoe werken ze? Beton met verbeterd slagvastheid voor verdedigingsconstructies

Beton met verbeterd slagvastheid voor verdedigingsconstructies Een populatiedichtheidskaart maken

Een populatiedichtheidskaart maken  Nieuwe bossen kunnen het overstromingsrisico binnen 15 jaar verminderen

Nieuwe bossen kunnen het overstromingsrisico binnen 15 jaar verminderen Advies voor leraren:gebruik de zomer om je hart te beschermen tegen burn-out

Advies voor leraren:gebruik de zomer om je hart te beschermen tegen burn-out

- Elektronica

- Biologie

- Zonsverduistering

- Wiskunde

- French | Italian | Spanish | Portuguese | Swedish | German | Dutch | Danish | Norway |

-

Wetenschap © https://nl.scienceaq.com