Wetenschap

Nieuwe techniek werkt als versneller, rem voor microscopisch kleine druppels

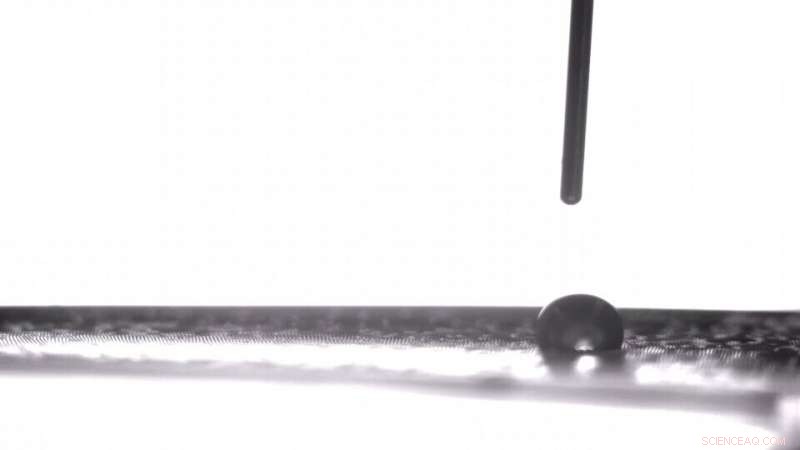

Een microscopisch kleine druppel water wordt afgezet op een elastische siliconenfilm. Door hun speciaal ontworpen films uit te rekken en te ontspannen, Nebraska-chemici Stephen Morin en Ali Mazaltarim hebben een ongekende controle getoond over de beweging van vloeistofdruppels op vlakke oppervlakken. Die controle zou de techniek bruikbaar kunnen maken in zelfreinigende materialen, waterwinning en andere toepassingen. Krediet:Stephen Morin / Ali Mazaltarim

Een minuscuul waterdruppeltje is in beweging, snelheid oppikken terwijl het langs een dun stuk glijdt, vlak terrein. Abrupt, het raakt een ruwe plek - het microscopische equivalent van glazen verkeersdrempels waarin de druppel neerslaat en stopt.

De druppel lijkt geparkeerd, op zijn plaats verankerd. Maar in tegenstelling tot hun macro-tegenhangers, deze mini verkeersdrempels zijn gemakkelijk plat te maken. Stephen Morin zou het weten; hij hield toezicht op hun bouw. Dus de scheikundige van de Universiteit van Nebraska-Lincoln gaat door met het uitrekken van het elastische materiaal waarop ze zitten, de weg effenen, en daar gaat de druppel weer, over het perfect horizontale oppervlak schieten.

De stop-and-go-prestatie is slechts een van de vele die de Morin Group heeft onthuld via zijn nieuwste huwelijk van chemie en elastische polymeren. De vruchten van dat huwelijk? Ongekende controle over het transport van microscopisch kleine druppeltjes, mogelijk nieuwe benaderingen van zelfreinigende materialen opleveren, technieken voor het oogsten van water en andere, meer geavanceerde technologieën.

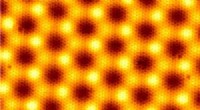

Centraal in de benadering van het team staat het concept van bevochtigbaarheid:of een druppel nu parelt of zich verspreidt op een oppervlak, het onthullen van dat oppervlak als hydrofoob of hydrofiel, respectievelijk. Geïnspireerd door baanbrekend onderzoek uit het begin van de jaren negentig, Morin en zijn laboratorium begonnen bevochtigingsgradiënten te creëren:oppervlakken bedekt met kleine chemische "hellingen" die ze aan de ene kant hydrofoob maken, maar aan de andere kant hydrofiel.

"Het blijkt dat als je zo'n chemisch patroon hebt, wanneer je een druppel aan het hydrofobe uiteinde plaatst, deze bevochtigingsgradiënt zal de druppel spontaan naar de hydrofiele kant drijven, " zei Morin, universitair hoofddocent scheikunde aan Nebraska.

Hoewel het op zich een interessant fenomeen is, Morin en promovendus Ali Mazaltarim wilden kijken of ze dat passieve transport konden omzetten in een actief, dynamisch proces dat zich beter leent voor toepassingen. Ze wendden zich tot het soort elastische materialen dat het team van Morin sinds 2015 met chemische patronen heeft gecoat. of het nu gaat om het maken van oppervlakken die alleen licht reflecteren als ze worden uitgerekt of om deeltjes te filteren op basis van vorm.

Zoals in het verleden vaak het geval was, het team begon met een zachte, plooibare siliconenfilm. De onderzoekers rekten die film op voordat ze hem behandelden met ultraviolet ozon om een microscopisch dunne laag silica te produceren. het hoofdbestanddeel van het meeste glas. Vervolgens bedekten ze bepaalde delen van het silica met dicht struikgewas van waterafstotende moleculen; andere secties werden grotendeels of volledig kaal gelaten, het creëren van een bevochtigingsgradiënt die druppeltjes van het hydrofobe naar het hydrofiele zou kunnen drijven.

Realtime controle krijgen over de beweging van die druppeltjes was toen een simpele en letterlijke kwestie van loslaten. Door de voorgerekte siliconenfilm te ontspannen, werden rimpels in het silica geïntroduceerd, vergelijkbaar met hoe een pleister die over de elleboog van een gebogen arm wordt geplaatst, zal rimpelen wanneer de arm wordt gestrekt. Morins team vermoedde dat die rimpels genoeg ruwheid konden introduceren om de snelheid van de druppeltjes te vertragen, zelfs op de hydrofobe delen van het oppervlak.

Experimenten bevestigden de hypothese:in hun volledig ontspannen, gerimpelde staat, de hydrofobe rekken zouden de druppels allemaal samen kunnen stoppen; in hun volledig strakke, gladde toestand, ze vervoerden de druppeltjes zoals ze normaal zouden doen.

De onderzoekers hebben die controle sindsdien aangescherpt door de films uit te rekken en te ontspannen om de druppeltjes van seconde tot seconde te starten en te stoppen. Ze hebben zelfs laten zien dat ze de zwaartekracht kunnen uitdagen, transporting droplets up inclines steeper than those reported in prior research.

Rough riders

Whether, and how fast, a droplet will move depends in part on the severity of a wettability gradient. When the transition from hydrophobic to hydrophilic occurs over a short distance, the droplets speed across the surface; when that transition stretches over a longer distance, the droplets lumber at a slower pace. The "steeper" the gradient, met andere woorden, the greater the driving force and velocity of the droplets. Other factors, including droplet size, are well-known contributors, te.

But the team was also finding that its acceleration and braking systems depended not just on the presence of the microscopic speed bumps, but also their height and spacing, both of which seemed to be influencing droplet velocity. From a mathematical and theoretical standpoint, the team realized, the roughness of the surface wasn't getting its due.

To better understand and predict how roughness was affecting droplet transport, Morin and Mazaltarim incorporated the variable into a couple of equations that are traditionally used to quantify the phenomenon. After some tweaking and experimental verification, their resulting model predicted the specific roughness needed to slow or stop a droplet of any given size—along with the minimum size needed to overcome that roughness and other factors that resist a droplet's movement.

Dat, beurtelings, allowed the team to craft surfaces that would transport larger droplets while leaving smaller ones in place, or trigger the departure of the latter only when stretching the elastic film beyond a certain threshold. En dat, the team said, could prove useful in sorting different liquids for analytical or other purposes.

The ability of such a simple technique to yield such precise, predictable behavior makes it promising for a range of other applications, Morin said. The team has already illustrated its potential in self-cleaning materials by dirtying an elastic surface with metal dust, then stretching it to trigger a cascade of droplets that carried away all dust in their path. The harvesting of water for urban agriculture, livestock or potable water might benefit from a similar approach.

"You could imagine fabrics where you collect droplets at one section, " Morin said, "and then you actuate the surface, which then drives them to some sort of a storage container."

There's also the possibility of expanding on the functionality of materials that are designed to remove sweat from skin or droplets from other surfaces. The latter could potentially help cool energy-generating systems that produce sizable amounts of heat.

"A lot of research in that area focuses on hydrophobic and superhydrophobic surfaces that have unique heat-exchange properties, " Morin said. "One could use the evaporative cooling effect of sweat as inspiration. But we imagine a more active system, where you're literally using a droplet to collect heat and then actively moving it somewhere else to remove that heat.

"That's a good thing if you're actively trying to cool any sort of a device. This just presents a new way of achieving that type of outcome."

Further down the line, Morin sees promise for calibrating the technique to transport droplets in two dimensions rather than just one. Managing that, hij zei, could make it a viable alternative in so-called lab-on-a-chip technologies that direct, mix and then analyze microscopic samples of liquids.

"We have the ability to really dial in the properties of the gradients and how they couple to the micro-texture of the surface, " Morin said. "So I think there's a lot of leeway in terms of how you design the system to get a specific performance outcome."

The team reported its findings in the journal Natuurcommunicatie .

NASA kijkt naar de regenval van Barry

NASA kijkt naar de regenval van Barry Belangrijkste verschillen tussen C3, C4 en CAM Fotosynthese

Belangrijkste verschillen tussen C3, C4 en CAM Fotosynthese De opwarming van de aarde weerspiegelt de omstandigheden die leiden tot de grootste uitstervingsgebeurtenis van de aarde, studie zegt:

De opwarming van de aarde weerspiegelt de omstandigheden die leiden tot de grootste uitstervingsgebeurtenis van de aarde, studie zegt: Principes van pneumatische systemen

Principes van pneumatische systemen NASA-satellietbeelden laten zien dat Teddy consolideert

NASA-satellietbeelden laten zien dat Teddy consolideert

Hoofdlijnen

- Ideeën voor een Sunscreen Science Fair Project

- De genetica van schijfziekte bij honden ontrafelen

- Chromosoomorganisatie komt voort uit 1-D-patronen

- Onderzoekers leggen de basis vast voor de ontwikkeling van ledematen van gewervelde dieren in kraakbeenvissen

- Onderzoek toont aan dat bodemradar fijne wortels in gewassen kan detecteren

- Knollen in de problemen

- Hoe het boren naar olie in het Arctic National Wildlife Refuge van invloed kan zijn op dieren in het wild

- De geesten van HeLa:hoe verkeerde identificatie van cellijnen de wetenschappelijke literatuur besmet

- Hoeveel onontdekte wezens zijn er in de oceaan?

- Nanotech in de ruimte:experiment om de beproevingen van een baan te doorstaan

- Kunnen hennep nanosheets grafeen omverwerpen om de ideale supercondensator te maken?

- Bacteriën versnipperen technologie om resistente superbacteriën te bestrijden

- Een touw op nanoschaal, en weer een stap in de richting van complexe nanomaterialen die zichzelf assembleren

- Nanopore-technologie maakt sprong van DNA-sequencing naar het identificeren van eiwitten

Vissersvrouwen dragen tonnen vis bij, miljarden dollars aan de wereldwijde visserij

Vissersvrouwen dragen tonnen vis bij, miljarden dollars aan de wereldwijde visserij Brandweerlieden proberen branden snel te doven, vermijd megabranden

Brandweerlieden proberen branden snel te doven, vermijd megabranden Levenscyclus van zadelrobben

Levenscyclus van zadelrobben Veranderende bewoonbaarheid van Mars vastgelegd door oude duinvelden in Gale-krater

Veranderende bewoonbaarheid van Mars vastgelegd door oude duinvelden in Gale-krater Wat wereldwijde klimaatverandering kan betekenen voor bladafval in beken en rivieren

Wat wereldwijde klimaatverandering kan betekenen voor bladafval in beken en rivieren Lasers gebruikt om eerste boornitride nanobuisgaren te maken (met video)

Lasers gebruikt om eerste boornitride nanobuisgaren te maken (met video) Geologen lossen puzzel op die waardevolle afzettingen van zeldzame aardelementen kan voorspellen

Geologen lossen puzzel op die waardevolle afzettingen van zeldzame aardelementen kan voorspellen Meer beenruimte, minder gesprek voor Uber-rijders die betalen

Meer beenruimte, minder gesprek voor Uber-rijders die betalen

- Elektronica

- Biologie

- Zonsverduistering

- Wiskunde

- French | Italian | Spanish | Portuguese | Swedish | German | Dutch | Danish | Norway |

-

Wetenschap © https://nl.scienceaq.com